2.4_Address_Spaces_in_CUDA

2.4 Address Spaces in CUDA

As every beginning CUDA programmer knows, the address spaces for the CPU and GPU are separate. The CPU cannot read or write the GPU's device memory, and in turn, the GPU cannot read or write the CPU's memory. As a result, the application must explicitly copy data to and from the GPU's memory in order to process it.

The reality is a bit more complicated, and it has gotten even more so as CUDA has added new capabilities such as mapped pinned memory and peer-to-peer access. This section gives a detailed description of how address spaces work in CUDA, starting from first principles.

2.4.1 VIRTUAL ADDRESSING: A BRIEF HISTORY

Virtual address spaces are such a pervasive and successful abstraction that most programmers use and benefit from them every day without ever knowing they exist. They are an extension of the original insight that it was useful to assign consecutive numbers to the memory locations in the computer. The standard unit of measure is the byte, so, for example, a computer with 64K of memory had memory locations 0..65535. The 16-bit values that specify memory locations are known as addresses, and the process of computing addresses and operating on the corresponding memory locations is collectively known as addressing.

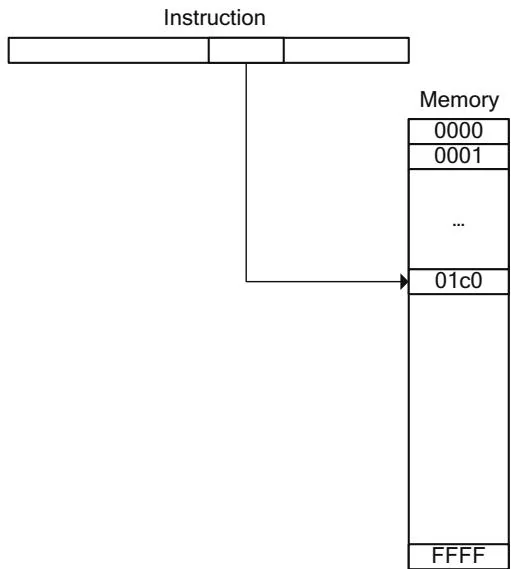

Early computers performed physical addressing. They would compute a memory location and then read or write the corresponding memory location, as shown in Figure 2.14. As software grew more complex and computers hosting multiple users or running multiple jobs grew more common, it became clear that allowing any program to read or write any physical memory location was unacceptable; software running on the machine could fatally corrupt other software by writing the wrong memory location. Besides the robustness concern, there were also security concerns: Software could spy on other software by reading memory locations it did not "own."

As a result, modern computers implement virtual address spaces. Each program (operating system designers call it a process) gets a view of memory similar to Figure 2.14, but each process gets its own address space. They cannot read or write memory belonging to other processes without special permission from the operating system. Instead of specifying a physical address, the machine instruction specifies a virtual address to be translated into a physical address by performing a series of lookups into tables that were set up by the operating system.

In most systems, the virtual address space is divided into pages, which are units of addressing that are at least 4096 bytes in size. Instead of referencing physical memory directly from the address, the hardware looks up a page table entry (PTE) that specifies the physical address where the page's memory resides.

Figure 2.14 Simple 16-bit address space.

It should be clear from Figure 2.15 that virtual addressing enables a contiguous virtual address space to map to discontinuous pages in physical memory. Also, when an application attempts to read or write a memory location whose page has not been mapped to physical memory, the hardware signals a fault that must be handled by the operating system.