10.2_Texture_Memory

10.2 Texture Memory

Before describing the features of the fixed-function texturing hardware, let's spend some time examining the underlying memory to which texture references may be bound. CUDA can texture from either device memory or CUDA arrays.

10.2.1 DEVICE MEMORY

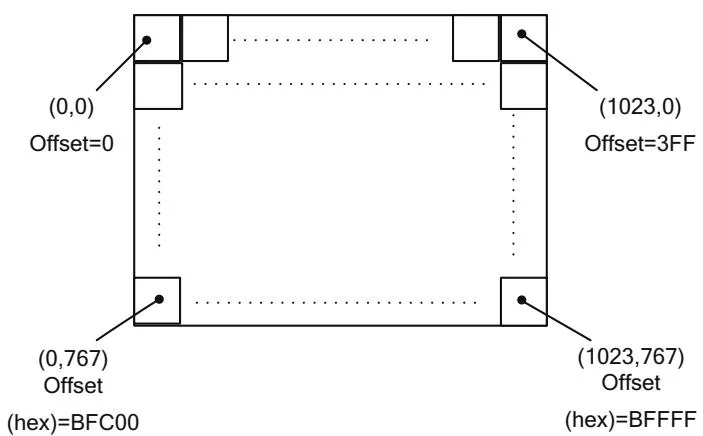

In device memory, the textures are addressed in row-major order. A 1024x768 texture might look like Figure 10.1, where Offset is the offset (in elements) from the base pointer of the image.

For a byte offset, multiply by the size of the elements.

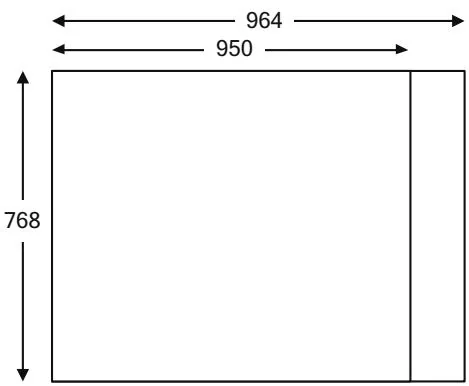

In practice, this addressing calculation only works for the most convenient of texture widths: 1024 happens to be convenient because it is a power of 2 and conforms to all manner of alignment restrictions. To accommodate less convenient texture sizes, CUDA implements pitch-linear addressing, where the width of the texture memory is different from the width of the texture. For less convenient widths, the hardware enforces an alignment restriction and the width in elements is treated differently from the width of the texture memory. For a texture width of 950, say, and an alignment restriction of 64 bytes, the width-in-bytes is padded to 964 (the next multiple of 64), and the texture looks like Figure 10.2.

In CUDA, the padded width in bytes is called the pitch. The total amount of device memory used by this image is 964x768 elements. The offset into the image now is computed in bytes, as follows.

Figure 10.1 1024x768 image.

Figure 10.2 950x768 image, with pitch.

Applications can call CUDAAllocPitch()/cuMemAllocPitch() to delegate selection of the pitch to the CUDA driver. In 3D, pitch-linear images of a given Depth are exactly like 2D images, with Depth 2D slices laid out contiguously in device memory.

10.2.2 CUDA ARRAYS AND BLOCK LINEAR ADDRESSING

CUDA arrays are designed specifically to support texturing. They are allocated from the same pool of physical memory as device memory, but they have an opaque layout and cannot be addressed with pointers. Instead, memory locations in a CUDA array must be identified by the array handle and a set of 1D, 2D, or 3D coordinates.

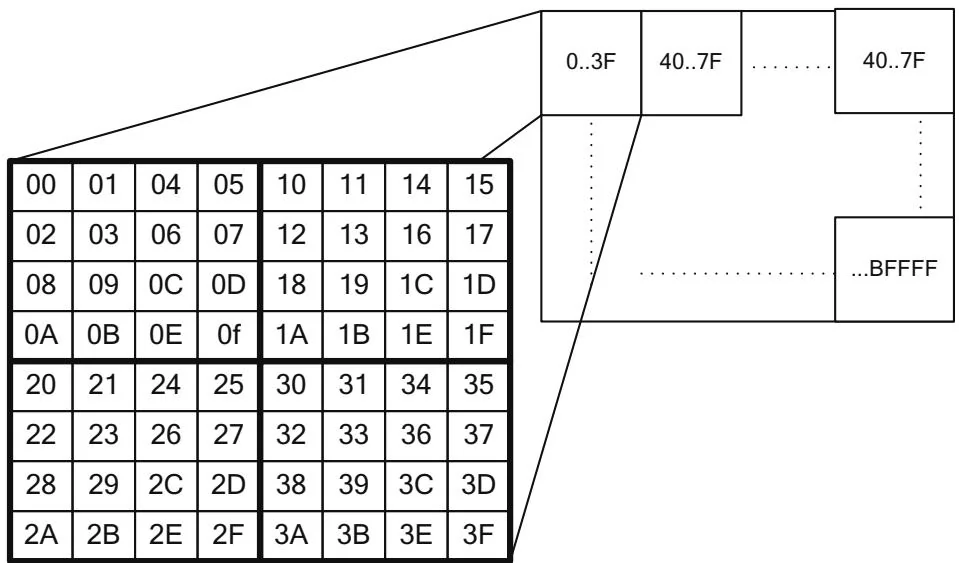

CUDA arrays perform a more complicated addressing calculation, designed so that contiguous addresses exhibit 2D or 3D locality. The addressing calculation is hardware-specific and changes from one hardware generation to the next. Figure 10.1 illustrates one of the mechanisms used: The two least significant address bits of row and column have been interleaved before undertaking the addressing calculation.

As you can see in Figure 10.3, bit interleaving enables contiguous addresses to have "dimensional locality": A cache line fill pulls in a block of pixels in a neighborhood rather than a horizontal span of pixels.² When taken to the

Figure 10.3 1024x768 image, interleaved bits.

limit, bit interleaving imposes some inconvenient requirements on the texture dimensions, so it is just one of several strategies used for the so-called "block linear" addressing calculation.

In device memory, the location of an image element can be specified by any of the following.

The base pointer, pitch, and a (XInBytes, Y) or (XInBytes, Y, Z) tuple

The base pointer and an offset as computed by Equation 10.1

The device pointer with the offset already applied

In contrast, when CUDA arrays do not have device memory addresses, so memory locations must be specified in terms of the CUDA array and a tuple (XInBytes, Y) or (XInBytes, Y, Z).

Creating and Destroying CUDA Arrays

Using the CUDA runtime, CUDA arrays may be created by calling CUDAAllocArray().

CUDAError_t CUDAAllocArray(struct CUDAArray **array, const struct CUDAChannelFormatDesc *desc, size_t width, size_t height __dv(0), unsigned int flags __dv(0));

array passes back the array handle, and desc specifies the number and type of components (e.g., 2 floats) in each array element. width specifies the width of the array in bytes. height is an optional parameter that specifies the height of the array; if the height is not specified,CORDarray() creates a 1D CUDA array.

The flags parameter is used to hint at the CUDA array's usage. As of this writing, the only flag isudaArraySurfaceLoadStore, which must be specified if the CUDA array will be used for surface read/write operations as described later in this chapter.

The __dv macro used for the height and flags parameters causes the declaration to behave differently, depending on the language. When compiled for C, it becomes a simple parameter, but when compiled for C++, it becomes a parameter with the specified default value.

The structureudaChannelFormatDesc describes the contents of a texture.

structudaChannelFormatDesc {

int x, y, z, w;

enumudaChannelFormatKind f;

};The x, y, z, and w members of the structure specify the number of bits in each member of the texture element. For example, a 1-element float texture will contain x==32 and the other elements will be 0. TheudaChannelFormat-Kind structure specifies whether the data is signed integer, unsigned integer, or floating point.

enumudaChannelFormatKind

{udaChannelFormatKindSigned $= 0$ ,udaChannelFormatKindUnsigned $= 1$ ,udaChannelFormatKindFloat $= 2$ ,udaChannelFormatKindNone $= 3$

};Developers can createudaChannelFormatDesc structures using the CUDA-CreateChannelDesc function.

CUDAChannelFormatDesc CUDACreateChannelDesc(int x, int y, int z, int w, CUDAChannelFormatKind kind);

Alternatively, a templated family of functions can be invoked as follows.

template<class T>udaCreateChannelDesc<T>();

where $\mathsf{T}$ may be any of the native formats supported by CUDA. Here are two examples of the specializations of this template.

```txt

template<> __inline__ host__udaChannelFormatDesc

cudaCreateChannelDesc(float>(void)

{

int e = (int) sizeof(float) * 8;

returnudaCreateChannelDesc(e, 0, 0, 0,udaChannelFormatKindFloat);

}CAUTION

When using the char data type, be aware that some compilers assume char is signed, while others assume it is unsigned. You can always make this distinction unambiguous with the signed keyword.

3D CUDA arrays may be allocated withudaMalloc3DArray().

CUDAError_t CUDAAlloc3DArray(struct CUDAArray** array, const struct CUDAChannelFormatDesc* desc, struct CUDAExtent extent, unsigned int flags __dv(0));

Rather than taking width, height, and depth parameters,udaMalloc3DArray() takes audaExtent structure.

struct CUDAExtent {

size_t width;

size_t height;

size_t depth;

};The flags parameter, like that ofudaMallocArray(), must beudaArray-SurfaceLoadStore if the CUDA array will be used for surface read/write operations.

NOTE

For array handles, the CUDA runtime and driver API are compatible with one another. The pointer passed back by CUDAAllocArray() can be cast to CUArray and passed to driver API functions such as cuArrayGetDescriptor().

Driver API

The driver API equivalents of CUDAAllocArray() and CUDAAlloc3DArray() are cuArrayCreate() and cuArray3DCreate(), respectively.

CUresult cuArrayCreate(CUarray *pHandle, const CUDA_ARRAY_DESCRIPTOR *pAllocateArray);

CUresult cuArray3DCreate(CUarray *pHandle, const CUDA_ARRAY3D_DESCRIPTOR *pAllocateArray);cuArray3DCreate() can be used to allocate 1D or 2D CUDA arrays by specifying 0 as the height or depth, respectively. The CUDA_ARRAY3D Descriptor structure is as follows.

typedef struct CUDA_ARRAY3D_DESCRIPTOR_st{ size_t Width; size_t Height; size_t Depth; CUarray_format Format; unsigned int NumChannels; unsigned int Flags; } CUDA_ARRAY3D_DESCRIPTOR;Together, the Format and NumChannels members describe the size of each element of the CUDA array: NumChannels may be 1, 2, or 4, and Format specifies the channels' type, as follows.

typedef enum CUarray_format_enum{ CU_AD_FORMAT_UNSGNED_INT8 $= 0\mathrm{x}01$ CU_AD_FORMAT_UNSGNED_INT16 $= 0\mathrm{x}02$ CU_AD_FORMAT_UNSGNED_INT32 $= 0\mathrm{x}03$ CU_AD_FORMAT_SIGNED_INT8 $= 0\mathrm{x}08$ CU_AD_FORMAT_SIGNED_INT16 $= 0\mathrm{x}09$ CU_AD_FORMAT_SIGNED_INT32 $= 0\mathrm{x}0a$ CU_AD_FORMAT_HALF $= 0\mathrm{x}10$ CU_AD_FORMAT_FLOAT $= 0\mathrm{x}20$ } CUarray_format;NOTE

The format specified in CUDA_ARRAY3D Descriptor is just a convenient way to specify the amount of data in the CUDA array. Textures bound to the CUDA array can specify a different format, as long as the bytes per element is the same. For example, it is perfectly valid to bind a texture reference to a CUDA array containing 4-component bytes (32 bits per element).

Sometimes CUDA array handles are passed to subroutines that need to query the dimensions and/or format of the input array. The following cuArray3DGet-Descriptor() function is provided for that purpose.

CUresult cuArray3DGetDescriptor(CUDA_ARRAY3D Descriptor *pArrayDescriptor, CUarray hArray);

Note that this function may be called on 1D and 2D CUDA arrays, even those that were created with cuArrayCreate().

10.2.3 DEVICE MEMORY VERSUS CUDA ARRAYS

For applications that exhibit sparse access patterns, especially patterns with dimensional locality (for example, computer vision applications), CUDA arrays are a clear win. For applications with regular access patterns, especially those with little to no reuse or whose reuse can be explicitly managed by the application in shared memory, device pointers are the obvious choice.

Some applications, such as image processing applications, fall into a gray area where the choice between device pointers and CUDA arrays is not obvious. All other things being equal, device memory is probably preferable to CUDA arrays, but the following considerations may be used to help in the decision-making process.

Until CUDA 3.2, CUDA kernels could not write to CUDA arrays. They were only able to read from them via texture intrinsics. CUDA 3.2 added the ability for Fermi-class hardware to access 2D CUDA arrays via "surface read/write" intrinsics.

CUDA arrays do not consume any CUDA address space.

On WDDM drivers (Windows Vista and later), the system can automatically manage the residence of CUDA arrays. They can be swapped into and out of device memory transparently, depending on whether they are needed by the CUDA kernels that are executing. In contrast, WDDM requires all device memory to be resident in order for any kernel to execute.

CUDA arrays can reside only in device memory, and if the GPU contains copy engines, it can convert between the two representations while transferring the data across the bus. For some applications, keeping a pitch representation in host memory and a CUDA array representation in device memory is the best fit.