6.2_Asynchronous_Memcpy

6.2 Asynchronous Memcpy

Like kernel launches, asynchronous memcpy calls return before the GPU has performed the memcpy in question. Because the GPU operates autonomously and can read or write the host memory without any operating system involvement, only pinned memory is eligible for asynchronous memcpy.

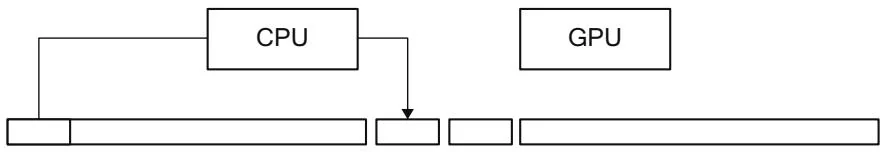

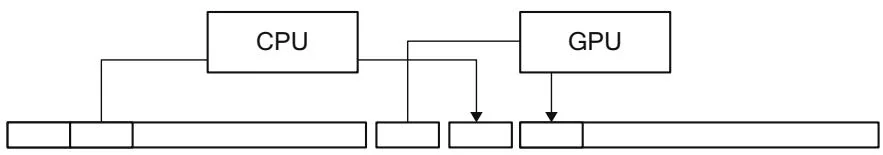

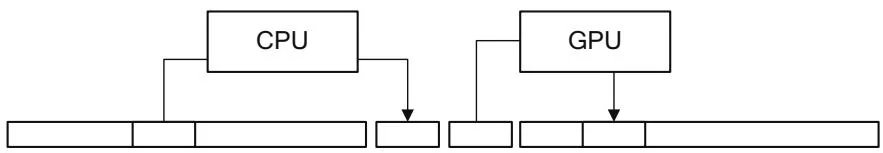

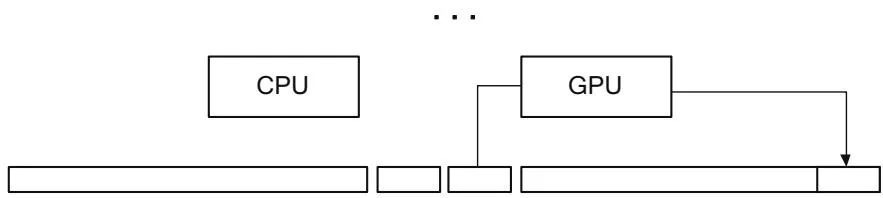

The earliest application for asynchronous memcpy in CUDA was hidden inside the CUDA 1.0 driver. The GPU cannot access pageable memory directly, so the driver implements pageable memcpy using a pair of pinned "staging buffers" that are allocated with the CUDA context. Figure 6.3 shows how this process works.

To perform a host device memcpy, the driver first "primes the pump" by copying to one staging buffer, then kicks off a DMA operation to read that data with the GPU. While the GPU begins processing that request, the driver copies more

"Prime the pump": CPU copies to first staging buffer

GPU pulls from first, while CPU copies to second

GPU pulls from second, while CPU copies to first

Figure 6.3 Pageable memcpy.

Final memcpy by GPU

data into the other staging buffer. The CPU and GPU keep ping-ponging between staging buffers, with appropriate synchronization, until it is time for the GPU to perform the final memcpy. Besides copying data, the CPU also naturally pages in any nonresident pages while the data is being copied.

6.2.1 ASYNCHRONOUS MEMCPY: HOST→DEVICE

As with kernel launches, asynchronous memcpy incurs fixed CPU overhead in the driver. In the case of host device memcpy, all memcpy below a certain size

are asynchronous, because the driver copies the source data directly into the command buffer that it uses to control the hardware.

We can write an application that measures asynchronous memcpy overhead, much as we measured kernel launch overhead earlier. The following code, in a program called nullHtoDMemcpyAsync.cu, reports that on a cg1.4xlarge instance in Amazon EC2, each memcpy takes 3.3 ms. Since PCI Express can transfer almost 2K in that time, it makes sense to examine how the time needed to perform a small memcpy grows with the size.

CUDART_CHECK(udaMalloc(&deviceInt,sizeof(int)));

CUDART_CHECK(udaHostAlloc(&hostInt,sizeof(int),0));

chTimerGetTime( &start); for(int $\mathrm{i} = 0$ :i $<$ cIterations; $\mathrm{i + + }$ ){ CUDART_CHECK(udaMemcpyAsync(deviceInt,hostInt,sizeof(int),udaMemcpyHostToDevice,NULL));

}

CUDART_CHECK(udaThreadSynchronize());

chTimerGetTime( &stop);The breakevenHtoDMemcpy. cu program measures memcpy performance for sizes from 4K to 64K. On a cg1.4xlarge instance in Amazon EC2, it generates Figure 6.4. The data generated by this program is clean enough to fit to a linear regression curve—in this case, with intercept and slope byte. The slope corresponds to 5.9GB/s, about the expected bandwidth from PCI Express 2.0.

Figure 6.4 Small host device memcpy performance.

6.2.2 ASYNCHRONOUS MEMCPY: DEVICE→HOST

The nullDtoHMemcpyNoSync.cu and breakevenDtoHMemcpy.cu programs perform the same measurements for small device→host memcpy. On our trusty Amazon EC2 instance, the minimum time for a memcpy is (Figure 6.5).

6.2.3 THE NULL STREAM AND CONCURRENCY BREAKS

Any streamed operation may be called with NULL as the stream parameter, and the operation will not be initiated until all the preceding operations on the GPU have been completed.4 Applications that have no need for copy engines to overlap memcpy operations with kernel processing can use the NULL stream to facilitate CPU/GPU concurrency.

Once a streamed operation has been initiated with the NULL stream, the application must use synchronization functions such as cuCtxSynchronize() or CUDAThreadSynchronize() to ensure that the operation has been completed before proceeding. But the application may request many such operations before performing the synchronization. For example, the application may

Figure 6.5 Small device→host memcpy performance.

perform an asynchronous host device memcpy, one or more kernel launches, and an asynchronous device host memcpy before synchronizing with the context. The cuCtxSynchronize() or CUDAThreadSynchronize() call returns once the GPU has performed the most recently requested operation. This idiom is especially useful when performing smaller memcpys or launching kernels that will not run for long. The CUDA driver takes valuable CPU time to write commands to the GPU, and overlapping that CPU execution with the GPU's processing of the commands can improve performance.

Note: Even in CUDA 1.0, kernel launches were asynchronous. As a result, the NULL stream is implicitly specified to all kernel launches if no stream is given.

BreakingConcurrency

Whenever an application performs a full CPU/GPU synchronization (having the CPU wait until the GPU is completely idle), performance suffers. We can measure this performance impact by switching our NULL-memcpy calls from asynchronous ones to synchronous ones just by changing theudaMemcpyAsync() calls toudaMemcpy() calls. The nullDtoHMemcpySync.cu program does just that for device→host memcpy.

On our trusty Amazon cg1.4xlarge instance, nullDtoHMemcpySync.cu reports about per memcpy. If a Windows driver has to perform a kernel thunk, or the driver on an ECC-enabled GPU must check for ECC errors, full GPU synchronization is much costlier.

Explicit ways to perform this synchronization include the following.

cuCtxSynchronize()/cudaDeviceSynchronize()

cuStreamSynchronize()/cudaStreamSynchronize() on the NULL stream

Unstreamed memcpy between host and device—for example, cuMemcpyHtoD(), cuMemcpyDtoH(),udaMemcpy()

Other, more subtle ways to break CPU/GPU concurrency include the following.

Running with the CUDA-LaUNCH_BLOCKING environment variable set

Launching kernels that require local memory to be reallocated

Performing large memory allocations or host memory allocations

Destroying objects such as CUDA streams and CUDA events

Nonblocking Streams

To create a stream that is exempt from the requirement to synchronize with the NULL stream (and therefore less likely to suffer a "concurrency break" as described above), specify the CUDA_STREAM_NON_BLOCKING flag to cuStreamCreate() or the cuadaStreamNonBlocking flag to cuadaStreamCreateWithFlags().