5.2_Global_Memory

5.2 Global Memory

Global memory is the main abstraction by which CUDA kernels read or write device memory. Since device memory is directly attached to the GPU and read and written using a memory controller integrated into the GPU, the peak bandwidth is extremely high: typically more than 100G/s for high-end CUDA cards.

Device memory can be accessed by CUDA kernels using device pointers. The following simple memset kernel gives an example.

template<class T> global voidGPUmemset( int *base, int value, size_t N)

{ for ( size_t i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; i < N; i += gridDim.x*blockDim.x ) { base[i] = value; }The device pointer base resides in the device address space, separate from the CPU address space used by the host code in the CUDA program. As a result, host code in the CUDA program can perform pointer arithmetic on device pointers, but they may not dereference them.7

This kernel writes the integer value into the address range given by base and N. The references to blockIdx, blockDim, and gridDim enable the kernel to operate correctly, using whatever block and grid parameters were specified to the kernel launch.

5.2.1 POINTERS

When using the CUDA runtime, device pointers and host pointers both are typed as void . The driver API uses an integer-valued typedef called CUdeviceptr that is the same width as host pointers (i.e., 32 bits on 32-bit operating systems and 64 bits on 64-bit operating systems), as follows.

if defined(_x86_64) || defined(AMD64) || defined(_M_AMD64)

typedef unsigned long long CUdeviceptr;

#else

typedef unsigned int CUdeviceptr;

#endifThe uintptr_t type, available in <stdlib.h> and introduced in C++0x, may be used to portably convert between host pointers (void *) and device pointers (Udeviceptr), as follows.

CUdeviceptr devicePtr;

void *p;

p = (void *) (uintptr_t) devicePtr;

devicePtr = (CUdeviceptr) (uintptr_t) p;The host can do pointer arithmetic on device pointers to pass to a kernel or memcpy call, but the host cannot read or write device memory with these pointers.

32- and 64-Bit Pointers in the Driver API

Because the original driver API definition for a pointer was 32-bit, the addition of 64-bit support to CUDA required the definition of CUdeviceptr and, in turn, all driver API functions that took CUdeviceptr as a parameter, to change. cuMemAlloc(), for example, changed from

CUIresult CUDAAPI cuMemAlloc(CUdeviceptr *dptr, unsigned int bytesize); to

CUIresult CUDAAPI cuMemAlloc(CUdeviceptr *dptr, size_t bytesize);

To accommodate both old applications (which linked against a cuMemAlloc () with 32-bit CUdeviceptr and size) and new ones, CUDA.h includes two blocks of code that use the preprocessor to change the bindings without requiring function names to be changed as developers update to the new API.

First, a block of code surreptitiously changes function names to map to newer functions that have different semantics.

if defined(_CUDA_API_VERSION_INTERNAL) || _CUDA_API_VERSION >= 3020

#define cuDeviceTotalMem cuDeviceTotalMem_v2

...

#define cuTexRefGetAddress cuTexRefGetAddress_v2

#endif /* _CUDA_API_VERSION_INTERNAL || _CUDA_API_VERSION >= 3020 */This way, the client code uses the same old function names, but the compiled code generates references to the new function names with _v2 appended.

Later in the header, the old functions are defined as they were. As a result, developers compiling for the latest version of CUDA get the latest function definitions and semantics. CUDA.h uses a similar strategy for functions whose semantics changed from one version to the next, such as cuStreamDestroy().

5.2.2 DYNAMIC ALLOCATIONS

Most global memory in CUDA is obtained through dynamic allocation. Using the CUDA runtime, the functions

cudaError_t CUDAAlloc(void **, size_t);

cudaError_t CUDAFree(void);

allocate and free global memory, respectively. The corresponding driver API functions are

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemAlloc(CUdeviceptr *dptr, size_t bytesize);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemFree(CUdeviceptr dptr);

Allocating global memory is expensive. The CUDA driver implements a sub-allocated to satisfy small allocation requests, but if the subAllocator must create a new memory block, that requires an expensive operating system call to the kernel mode driver. If that happens, the CUDA driver also must synchronize with the GPU, which may break CPU/GPU concurrency. As a result, it's good practice to avoid allocating or freeing global memory in performance-sensitive code.

Pitched Allocations

The coalescing constraints, coupled with alignment restrictions for texturing and 2D memory copy, motivated the creation of pitched memory allocations. The idea is that when creating a 2D array, a pointer into the array should have the same alignment characteristics when updated to point to a different row. The pitch of the array is the number of bytes per row of the array.9 The pitch allocations take a width (in bytes) and height, pad the width to a suitable hardware-specific pitch, and pass back the base pointer and pitch of the allocation. By using these allocation functions to delegate selection of the pitch to the driver, developers can future-proof their code against architectures that widen alignment requirements.10

CUDA programs often must adhere to alignment constraints enforced by the hardware, not only on base addresses but also on the widths (in bytes) of memory copies and linear memory bound to textures. Because the alignment constraints are hardware-specific, CUDA provides APIs that enable developers to delegate the selection of the appropriate alignment to the driver. Using these APIs enables CUDA applications to implement hardware-independent code and to be "future-proof" against CUDA architectures that have not yet shipped.

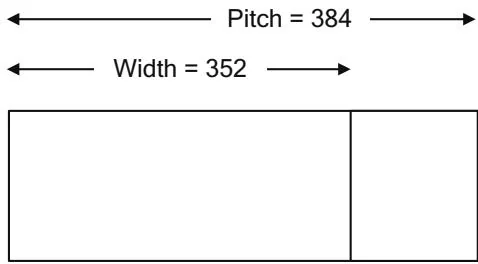

Figure 5.1 Pitch versus width.

Figure 5.1 shows a pitch allocation being performed on an array that is 352 bytes wide. The pitch is padded to the next multiple of 64 bytes before allocating the memory. Given the pitch of the array in addition to the row and column, the address of an array element can be computed as follows.

inline T \*

getElement(T \*base,size_t Pitch,int row,int col)

{ return(T\*)((char \*) base $^+$ row\*Pitch)+col;

}The CUDA runtime function to perform a pitched allocation is as follows.

template<class T> inline __host__udaError_tudaMallocPitch(T **devPtr, size_t *pitch, size_t widthInBytes, size_t height);The CUDA runtime also includes the function CUDAAlloc3D(), which allocates 3D memory regions using the CUDAPitchedPtr and CUDAExtent structures.

extern __host__udaError_t CUDARTAPI CUDAAlloc3D(struct CUDAPitchedPtr* pitchedDevPtr, struct CUDAExtent extent);cudaPitchedPtr, which receives the allocated memory, is defined as follows.

struct CUDAPitchedPtr {

void *ptr;

size_t pitch;

size_t xsize;

size_t ysize;

};cudaPitchedPtr::ptr specifies the pointer;udaPitchedPtr::pitch specifies the pitch (width in bytes) of the allocation; andudaPitchedPtr::xsize andudaPitchedPtr::ysize are the logical width and height of the allocation, respectively. cudaExtent is defined as follows.

struct CUDAExtent {

size_t width;

size_t height;

size_t depth;

};sudoExtent::width is treated differently for arrays and linear device memory. For arrays, it specifies the width in array elements; for linear device memory, it specifies the pitch (width in bytes).

The driver API function to allocate memory with a pitch is as follows.

CUIresult CUDAAPI cuMemAllocPitch(CUdeviceptr *dptr, size_t *pPitch, size_t WidthInBytes, size_t Height, unsigned int ElementSizeBytes);

The ElementSizeBytes parameter may be 4, 8, or 16 bytes, and it causes the allocation pitch to be padded to 64-, 128-, or 256-byte boundaries. Those are the alignment requirements for coalescing of 4-, 8-, and 16-byte memory transactions on SM 1.0 and SM 1.1 hardware. Applications that are not concerned with running well on that hardware can specify 4.

The pitch returned by CUDAAllocPitch() / cuMemAllocPitch() is the width-in-bytes passed in by the caller, padded to an alignment that meets the alignment constraints for both coalescing of global load/store operations, and texture bind APIs. The amount of memory allocated is height *pitch.

For 3D arrays, developers can multiply the height by the depth before performing the allocation. This consideration only applies to arrays that will be accessed via global loads and stores, since 3D textures cannot be bound to global memory.

Allocations within Kernels

Fermi-class hardware can dynamically allocate global memory using malloc(). Since this may require the GPU to interrupt the CPU, it is potentially slow. The sample program mallocSpeed.cu measures the performance of malloc() and free() in kernels.

Listing 5.3 shows the key kernels and timing routine in mallocSpeed.cu. As an important note, the cudaSetDeviceLimit() function must be called with

cudaLimitMallocHeapSize before malloc() may be called in kernels. The invocation in mallocSpeed.cu requests a full gigabyte (230 bytes).

CUDART_CHECK(udaDeviceSetLimit(cudaLimitMallocHeapSize, 1<<30));

When CUDADeviceSetLimit() is called, the requested amount of memory is allocated and may not be used for any other purpose.

Listing 5.3 MallocSpeed function and kernels.

.global__void

AllocateBuffers( void **out, size_t N)

{

size_t i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

out[i] = malloc(N);

}

global__void

FreeBuffers( void **in )

{

size_t i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

free(in[i]);

}

cudaeError_t

MallocSpeed( double *msPerAlloc, double *msPerFree,

void **devicePointers, size_t N,

cudaEvent_t evStart, cudaEvent_t evStop,

int cBlocks, int cThreads);

float etAlloc, etFree;

cudaeError_t status;

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventRecord( evStart ) );

AllocateBuffers<<cBlocks,cThreads>>>( devicePointers,N);

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventRecord( evStop ) );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaThreadSynchronize() );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaGetLastError() );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventElapsedTime( &etAlloc, evStart, evStop ) );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventRecord( evStart ) );

FreeBuffers<<cBlocks,cThreads>>>( devicePointers );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventRecord( evStop ) );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaThreadSynchronize() );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaGetLastError() );

CUDART_CHECK( cudaEventElapsedTime( &etFree, evStart, evStop ) );

*msPerAlloc = etAlloc / (double) (cBlocks*cThreads);

*msPerFree = etFree / (double) (cBlocks*cThreads);Error: return status; }Listing 5.4 shows the output from a sample run of mallocSpeed.cu on Amazon's cg1.4xlarge instance type. It is clear that the allocator is optimized for small allocations: The 64-byte allocations take an average of 0.39 microseconds to perform, while allocations of 12K take at least 3 to 5 microseconds. The first result (155 microseconds per allocation) is having 1 thread per each of 500 blocks allocate a 1MB buffer.

Listing 5.4 Sample mallocSpeed.cu output.

Microseconds per alloc/free (1 thread per block):

alloc free

154.93 4.57

Microseconds per alloc/free (32-512 threads per block, 12K allocations):

32 64 128 256 512

alloc free alloc free alloc free alloc free alloc free

3.53 1.18 4.27 1.17 4.89 1.14 5.48 1.14 10.38 1.11

Microseconds per alloc/free (32-512 threads per block, 64-byte allocations):

32 64 128 256 512

alloc free alloc free alloc free alloc free alloc free

0.35 0.27 0.37 0.29 0.34 0.27 0.37 0.22 0.53 0.27IMPORTANT NOTE

Memory allocated by invoking malloc() in a kernel must be freed by a kernel calling free(). Calling cudaFree() on the host will not work.

5.2.3 QUERYING THE AMOUNT OF GLOBAL MEMORY

The amount of global memory in a system may be queried even before CUDA has been initialized.

CUDA Runtime

Call CUDAGetDeviceProperties() and examine CUDADeviceProp.totalGlobalMem:

size_t totalGlobalMem; /**< Global memory on device in bytes */.

Driver API

Call this driver API function.

CUresult CUDAAPI cuDeviceTotalMem(size_t *bytes, CUdevice dev);

WDDM and Available Memory

The Windows Display Driver Model (WDDM) introduced with Windows Vista changed the model for memory management by display drivers to enable chunks of video memory to be swapped in and out of host memory as needed to perform rendering. As a result, the amount of memory reported by cuDeviceTotalMem() / CUDADeviceProp::totalGlobalMem will not exactly reflect the amount of physical memory on the card.

5.2.4 STATIC ALLOCATIONS

Applications can statically allocate global memory by annotating a memory declaration with the device keyword. This memory is allocated by the CUDA driver when the module is loaded.

CUDA Runtime

Memory copies to and from statically allocated memory can be performed byudaMemcpyToSymbol() andudaMemcpyFromSymbol().

varaError_t CUDAMemcpyToSymbol(

char *symbol,

const void *src,

size_t count,

size_t offset = 0,

enum CUDAMemcpyKind kind = CUDAMemcpyHostToDevice

);

cudaError_t CUDAMemcpyFromSymbol(

void *dst,

char *symbol,

size_t count,

size_t offset = 0,

enum CUDAMemcpyKind kind = CUDAMemcpyDeviceToHost

);When callingCORDemcpyToSymbol() orCORDemcpyFromSymbol(),do not enclose the symbol name in quotation marks. In other words, use

sudoMemcpyToSymbol(g_xOffset, poffsetx, WidthHeightsizeof(int)); not

CUDAMemoryToSymbol("g_xOffset", poffsetx, ...);

Both formulations work, but the latter formulation will compile for any symbol name (even undefined symbols). If you want the compiler to report errors for invalid symbols, avoid the quotation marks.

CUDA runtime applications can query the pointer corresponding to a static allocation by calling CUDAGetSymbolAddress().

cudaError_t CUDAGetSymbolAddress(void **devPtr, char *symbol);

Beware: It is all too easy to pass the symbol for a statically declared device memory allocation to a CUDA kernel, but this does not work. You must call CUDAGetSymbolAddress() and use the resulting pointer.

Driver API

Developers using the driver API can obtain pointers to statically allocated memory by calling cuModuleGetGlobal().

CUresult CUDAAPI cuModuleGetGlobal(CUdeviceptr *dptr, size_t *bytes, CUmodule hmod, const char *name);

Note that cuModuleGetGlobal() passes back both the base pointer and the size of the object. If the size is not needed, developers can pass NULL for the bytes parameter. Once this pointer has been obtained, the memory can be accessed by passing the CUdeviceptr to memory copy calls or CUDA kernel invocations.

5.2.5 MEMSET apis

For developer convenience, CUDA provides 1D and 2D memset functions. Since they are implemented using kernels, they are asynchronous even when no stream parameter is specified. For applications that must serialize the execution of a memset within a stream, however, there are *Async() variants that take a stream parameter.

CUDA Runtime

The CUDA runtime supports byte-sized memset only:

cudaError_t CUDAMemset(void *devPtr, int value, size_t count);

cudaError_t CUDAMemset2D(void *devPtr, size_t pitch, int value, size_t width, size_t height);

The pitch parameter specifies the bytes per row of the memset operation.

Table 5.2 Memset Variations

Driver API

The driver API supports 1D and 2D memset of a variety of sizes, shown in Table 5.2. These memset functions take the destination pointer, value to set, and number of values to write starting at the base address. The pitch parameter is the bytes per row (not elements per row!).

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD8(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, unsigned char uc, size_t N);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD16(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, unsigned short us, size_t N);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD32(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, unsigned int ui, size_t N);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD2D8(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, size_t dstPitch, unsigned char uc, size_t Width, size_t Height);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD2D16(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, size_t dstPitch, unsigned short us, size_t Width, size_t Height);

CUresult CUDAAPI cuMemsetD2D32(CUdeviceptr dstDevice, size_t dstPitch, unsigned int ui, size_t Width, size_t Height);Now that CUDA runtime and driver API functions can peacefully coexist in the same application, CUDA runtime developers can use these functions as needed. The unsigned char, unsigned short, and unsigned int parameters just specify a bit pattern; to fill a global memory range with some other type, such as float, use a volatile union to coerce the float to unsigned int.

5.2.6 POINTER QUERIES

CUDA tracks all of its memory allocations, and provides APIs that enable applications to query CUDA about pointers that were passed in from some other party. Libraries or plugins may wish to pursue different strategies based on this information.

CUDA Runtime

TheckaPointerGetAttributes() function takes a pointer as input and passes back ackaPointerAttributes structure containing information about the pointer.

structCORDerAttributes {

enumCORDMemoryTypememoryType;

int device;

void*devicePointer;

void*hostPointer;

}When UVA is in effect, pointers are unique process-wide, so there is no ambiguity as to the input pointer's address space. When UVA is not in effect, the input pointer is assumed to be in the current device's address space (Table 5.3).

Driver API

Developers can query the address range where a given device pointer resides using the cuMemGetAddressRange() function.

CUIresult CUDAAPI cuMemGetAddressRange(CUdeviceptr *pbase, size_t *psize, CUdeviceptr dptr);

This function takes a device pointer as input and passes back the base and size of the allocation containing that device pointer.

Table 5.3CORDPointerAttributes Members

With the addition of UVA in CUDA 4.0, developers can query CUDA to get even more information about an address using cuPointerGetAttribute().

CUIresult CUDAAPI cuPointerGetAttribute(void *data, CUpointer_attribute attribute, CUdeviceptr ptr);

This function takes a device pointer as input and passes back the information corresponding to the attribute parameter, as shown in Table 5.4. Note that for unified addresses, using CU_POINTER_ATTRIBUTE_DEVICE_POINTER or CU_POINTER_ATTRIBUTE_HOST_POINTER will cause the same pointer value to be returned as the one passed in.

Kernel Queries

On SM 2.x (Fermi) hardware and later, developers can query whether a given pointer points into global space. The __isGlobal() intrinsic

unsigned int __isGlobal(const void *p);

returns 1 if the input pointer refers to global memory and 0 otherwise.

Table 5.4 cuPointerAttribute Usage

5.2.7 PEER-TO-PEER ACCESS

Under certain circumstances, SM 2.0-class and later hardware can map memory belonging to other, similarly capable GPUs. The following conditions apply.

UVA must be in effect.

Both GPUs must be Fermi-class and be based on the same chip.

The GPUs must be on the same I/O hub.

Since peer-to-peer mapping is intrinsically a multi-GPU feature, it is described in detail in the multi-GPU chapter (see Section 9.2).

5.2.8 READING AND WRITING GLOBAL MEMORY

CUDA kernels can read or write global memory using standard C semantics such as pointer indirection (operator*, operator->) or array subscripting (operator[]) . Here is a simple templatized kernel to write a constant into a memory range.

template<class T> global void GlobalWrites(T *out, T value, size_t N) {

for (size_t i = BlockIdx.x*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x; i < N; i += blockDim.x*gridDim.x) {

out[i] = value;

}

}This kernel works correctly for any inputs: any component size, any block size, any grid size. Its code is intended more for illustrative purposes than maximum performance. CUDA kernels that use more registers and operate on multiple values in the inner loop go faster, but for some block and grid configurations, its performance is perfectly acceptable. In particular, provided the base address and block size are specified correctly, it performs coalesced memory transactions that maximize memory bandwidth.

5.2.9 COALESCING CONSTRAINTS

For best performance when reading and writing data, CUDA kernels must perform coalesced memory transactions. Any memory transaction that does not meet the full set of criteria needed for coalescing is "uncoalesced." The penalty

for uncoalesced memory transactions varies from 2x to 8x, depending on the chip implementation. Coalesced memory transactions have a much less dramatic impact on performance on more recent hardware, as shown in Table 5.5.

Transactions are coalesced on a per-warp basis. A simplified set of criteria must be met in order for the memory read or write being performed by the warp to be coalesced.

The words must be at least 32 bits in size. Reading or writing bytes or 16-bit words is always uncoalesced.

The addresses being accessed by the threads of the warp must be contiguous and increasing (i.e., offset by the thread ID).

The base address of the warp (the address being accessed by the first thread in the warp) must be aligned as shown in Table 5.6.

Table 5.5 Bandwidth Penalties for Uncoalesced Memory Access

Table 5.6 Alignment Criteria for Coalescing

8- and 16-bit memory accesses are always uncoalesced.

The ElementSizeBytes parameter to cuMemAllocPitch() is intended to accommodate the size restriction. It specifies the size in bytes of the memory accesses intended by the application, so the pitch guarantees that a set of coalesced memory transactions for a given row of the allocation also will be coalesced for other rows.

Most kernels in this book perform coalesced memory transactions, provided the input addresses are properly aligned. NVIDIA has provided more detailed architecture-specific information on how global memory transactions are handled, as detailed below.

SM 1.x (Tesla)

SM 1.0 and SM 1.1 hardware require that each thread in a warp access adjacent memory locations in sequence, as described above. SM 1.2 and 1.3 hardware relaxed the coalescing constraints somewhat. To issue a coalesced memory request, divide each 32-thread warp into two "half warps," lanes 0-15 and lanes 16-31. To service the memory request from each half-warp, the hardware performs the following algorithm.

Find the active thread with the lowest thread ID and locate the memory segment that contains that thread's requested address. The segment size depends on the word size: 1-byte requests result in 32-byte segments; 2-byte requests result in 64-byte segments; and all other requests result in 128-byte segments.

Find all other active threads whose requested address lies in the same segment.

If possible, reduce the segment transaction size to 64 or 32 bytes.

Carry out the transaction and mark the services threads as inactive.

Repeat steps 1-4 until all threads in the half-warp have been serviced.

Although these requirements are somewhat relaxed compared to the SM 1.0-1.1 constraints, a great deal of locality is still required for effective coalescing. In practice, the relaxed coalescing means the threads within a warp can permute the inputs within small segments of memory, if desired.

SM 2.x (Fermi)

SM 2.x and later hardware includes L1 and L2 caches. The L2 cache services the entire chip; the L1 caches are per-SM and may be configured to be 16K or 48K

in size. The cache lines are 128 bytes and map to 128-byte aligned segments in device memory. Memory accesses that are cached in both L1 and L2 are serviced with 128-byte memory transactions, whereas memory accesses that are cached in L2 only are serviced with 32-byte memory transactions. Caching in L2 only can therefore reduce overfetch, for example, in the case of scattered memory accesses.

The hardware can specify the cacheability of global memory accesses on a per-instruction basis. By default, the compiler emits instructions that cache memory accesses in both L1 and L2 (-xptexas -dlcm=ca). This can be changed to cache in L2 only by specifying -xptexas -dlcm=cg. Memory accesses that are not present in L1 but cached in L2 only are serviced with 32-byte memory transactions, which may improve cache utilization for applications that are performing scattered memory accesses.

Reading via pointers that are declared volatile causes any cached results to be discarded and for the data to be refetched. This idiom is mainly useful for polling host memory locations. Table 5.7 summarizes how memory requests by a warp are broken down into 128-byte cache line requests.

NOTE

On SM 2.x and higher architectures, threads within a warp can access any words in any order, including the same words.

Table 5.7 SM 2.x Cache Line Requests

SM 3.x (Kepler)

The L2 cache architecture is the same as SM 2.x. SM 3.x does not cache global memory accesses in L1. In SM 3.5, global memory may be accessed via the texture cache (which is 48K per SM in size) by accessing memory via const restricted pointers or by using the __1dg() intrinsics in sm_35_intrinsics.h. As when texturing directly from device memory, it is important not to access memory that might be accessed concurrently by other means, since this cache is not kept coherent with respect to the L2.

5.2.10 MICROBENCHMARKS:PEAK MEMORY BANDWIDTH

The source code accompanying this book includes microbenchmarks that determine which combination of operand size, loop unroll factor, and block size maximizes bandwidth for a given GPU. Rewriting the earlier GlobalWrites code as a template that takes an additional parameter (the number of writes to perform in the inner loop) yields the kernel in Listing 5.5.

Listing 5.5 GlobalWrites kernel.

template<class T, const int n> global void GlobalWrites(T *out, T value, size_t N) {

size_t i;

for (i = n*blockIdx.x*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x; i < N-n*blockDim.x*gridDim.x; i += n*blockDim.x*gridDim.x) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++) {