README

Chapter 21: Exploration and Discovery

This chapter explores patterns that enable intelligent agents to actively seek out novel information, uncover new possibilities, and identify unknown unknowns within their operational environment. Exploration and discovery differ from reactive behaviors or optimization within a predefined solution space. Instead, they focus on agents proactively venturing into unfamiliar territories, experimenting with new approaches, and generating new knowledge or understanding. This pattern is crucial for agents operating in open-ended, complex, or rapidly evolving domains where static knowledge or pre-programmed solutions are insufficient. It emphasizes the agent's capacity to expand its understanding and capabilities.

Practical Applications & Use Cases

AI agents possess the ability to intelligently prioritize and explore, which leads to applications across various domains. By autonomously evaluating and ordering potential actions, these agents can navigate complex environments, uncover hidden insights, and drive innovation. This capacity for prioritized exploration enables them to optimize processes, discover new knowledge, and generate content.

Examples:

Scientific Research Automation: An agent designs and runs experiments, analyzes results, and formulates new hypotheses to discover novel materials, drug candidates, or scientific principles.

Game Playing and Strategy Generation: Agents explore game states, discovering emergent strategies or identifying vulnerabilities in game environments (e.g., AlphaGo).

Market Research and Trend Spotting: Agents scan unstructured data (social media, news, reports) to identify trends, consumer behaviors, or market opportunities.

Security Vulnerability Discovery: Agents probe systems or codebases to find security flaws or attack vectors.

Creative Content Generation: Agents explore combinations of styles, themes, or data to generate artistic pieces, musical compositions, or literary works.

Personalized Education and Training: AI tutors prioritize learning paths and content delivery based on a student's progress, learning style, and areas needing improvement.

Google Co-Scientist

An AI co-scientist is an AI system developed by Google Research designed as a computational scientific collaborator. It assists human scientists in research aspects such as hypothesis generation, proposal refinement, and experimental design. This system operates on the Gemini LLM..

The development of the AI co-scientist addresses challenges in scientific research. These include processing large volumes of information, generating testable hypotheses, and managing experimental planning. The AI co-scientist supports researchers by performing tasks that involve large-scale information processing and synthesis, potentially revealing relationships within data. Its purpose is to augment human cognitive processes by handling computationally demanding aspects of early-stage research.

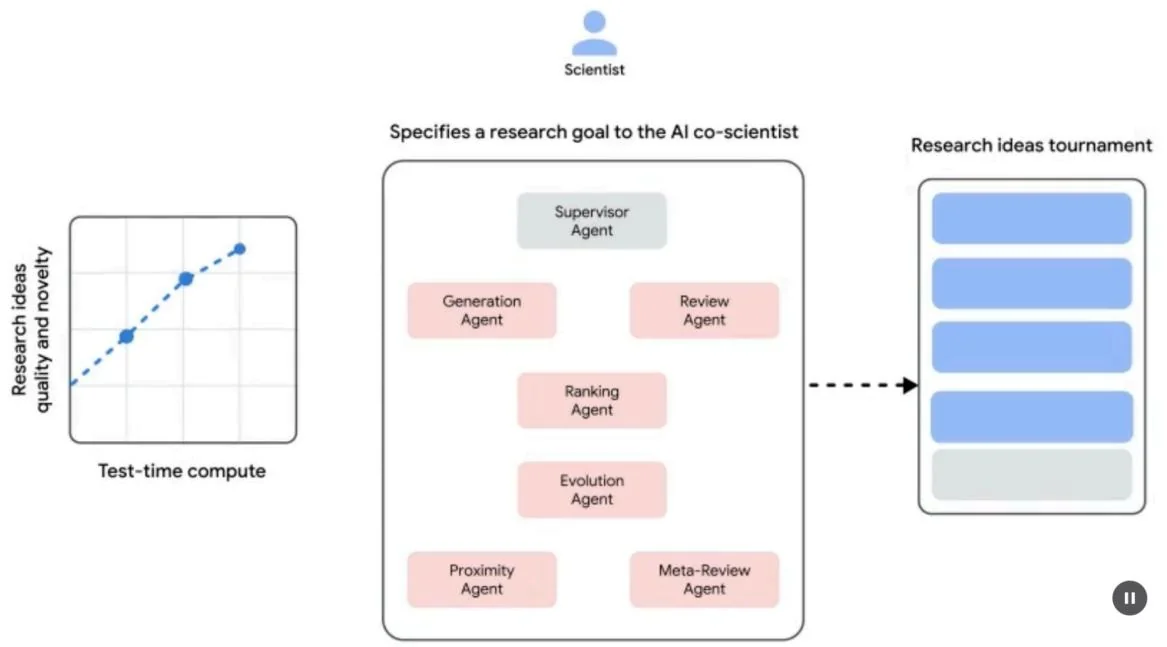

System Architecture and Methodology: The architecture of the AI co-scientist is based on a multi-agent framework, structured to emulate collaborative and iterative processes. This design integrates specialized AI agents, each with a specific role in contributing to a research objective. A supervisor agent manages and coordinates the activities of these individual agents within an asynchronous task execution framework that allows for flexible scaling of computational resources.

The core agents and their functions include (see Fig. 1):

Generation agent: Initiates the process by producing initial hypotheses through literature exploration and simulated scientific debates.

Reflection agent: Acts as a peer reviewer, critically assessing the correctness, novelty, and quality of the generated hypotheses.

Ranking agent: Employs an Elo-based tournament to compare, rank, and prioritize hypotheses through simulated scientific debates.

Evolution agent: Continuously refines top-ranked hypotheses by simplifying concepts, synthesizing ideas, and exploring unconventional reasoning.

Proximity agent: Computing a proximity graph to cluster similar ideas and assist in exploring the hypothesis landscape.

Meta-review agent: Synthesizes insights from all reviews and debates to identify common patterns and provide feedback, enabling the system to continuously improve.

The system's operational foundation relies on Gemini, which provides language understanding, reasoning, and generative abilities. The system incorporates

"test-time compute scaling," a mechanism that allocates increased computational resources to iteratively reason and enhance outputs. The system processes and synthesizes information from diverse sources, including academic literature, web-based data, and databases.

Fig. 1: (Courtesy of the Authors) AI Co-Scientist: Ideation to Validation

The system follows an iterative "generate, debate, and evolve" approach mirroring the scientific method. Following the input of a scientific problem from a human scientist, the system engages in a self-improving cycle of hypothesis generation, evaluation, and refinement. Hypotheses undergo systematic assessment, including internal evaluations among agents and a tournament-based ranking mechanism.

Validation and Results: The AI co-scientist's utility has been demonstrated in several validation studies, particularly in biomedicine, assessing its performance through automated benchmarks, expert reviews, and end-to-end wet-lab experiments.

Automated and Expert Evaluation: On the challenging GPQA benchmark, the system's internal Elo rating was shown to be concordant with the accuracy of its results, achieving a top-1 accuracy of on the difficult "diamond set". Analysis across over 200 research goals demonstrated that scaling test-time compute consistently improves the quality of hypotheses, as measured by the Elo rating. On a curated set of 15 challenging problems, the AI co-scientist outperformed other state-of-the-art AI models and the "best guess" solutions provided by human experts. In a small-scale evaluation, biomedical experts rated the co-scientist's outputs as

more novel and impactful compared to other baseline models. The system's proposals for drug repurposing, formatted as NIH Specific Aims pages, were also judged to be of high quality by a panel of six expert oncologists.

End-to-End Experimental Validation:

Drug Repurposing: For acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the system proposed novel drug candidates. Some of these, like KIRA6, were completely novel suggestions with no prior preclinical evidence for use in AML. Subsequent in vitro experiments confirmed that KIRA6 and other suggested drugs inhibited tumor cell viability at clinically relevant concentrations in multiple AML cell lines.

Novel Target Discovery: The system identified novel epigenetic targets for liver fibrosis. Laboratory experiments using human hepatic organoids validated these findings, showing that drugs targeting the suggested epigenetic modifiers had significant anti-fibrotic activity. One of the identified drugs is already FDA-approved for another condition, opening an opportunity for repurposing.

Antimicrobial Resistance: The Al co-scientist independently recapitulated unpublished experimental findings. It was tasked to explain why certain mobile genetic elements (cf-PICls) are found across many bacterial species. In two days, the system's top-ranked hypothesis was that cf-PICls interact with diverse phage tails to expand their host range. This mirrored the novel, experimentally validated discovery that an independent research group had reached after more than a decade of research.

Augmentation, and Limitations: The design philosophy behind the AI co-scientist emphasizes augmentation rather than complete automation of human research. Researchers interact with and guide the system through natural language, providing feedback, contributing their own ideas, and directing the AI's exploratory processes in a "scientist-in-the-loop" collaborative paradigm. However, the system has some limitations. Its knowledge is constrained by its reliance on open-access literature, potentially missing critical prior work behind paywalls. It also has limited access to negative experimental results, which are rarely published but crucial for experienced scientists. Furthermore, the system inherits limitations from the underlying LLMs, including the potential for factual inaccuracies or "hallucinations".

Safety: Safety is a critical consideration, and the system incorporates multiple safeguards. All research goals are reviewed for safety upon input, and generated hypotheses are also checked to prevent the system from being used for unsafe or unethical research. A preliminary safety evaluation using 1,200 adversarial research

goals found that the system could robustly reject dangerous inputs. To ensure responsible development, the system is being made available to more scientists through a Trusted Tester Program to gather real-world feedback.

Hands-On Code Example

Let's look at a concrete example of agentic AI for Exploration and Discovery in action: Agent Laboratory, a project developed by Samuel Schmidgall under the MIT License.

"Agent Laboratory" is an autonomous research workflow framework designed to augment human scientific endeavors rather than replace them. This system leverages specialized LLMs to automate various stages of the scientific research process, thereby enabling human researchers to dedicate more cognitive resources to conceptualization and critical analysis.

The framework integrates "AgentRxiv," a decentralized repository for autonomous research agents. AgentRxiv facilitates the deposition, retrieval, and development of research outputs

Agent Laboratory guides the research process through distinct phases:

Literature Review: During this initial phase, specialized LLM-driven agents are tasked with the autonomous collection and critical analysis of pertinent scholarly literature. This involves leveraging external databases such as arXiv to identify, synthesize, and categorize relevant research, effectively establishing a comprehensive knowledge base for the subsequent stages.

Experimentation: This phase encompasses the collaborative formulation of experimental designs, data preparation, execution of experiments, and analysis of results. Agents utilize integrated tools like Python for code generation and execution, and Hugging Face for model access, to conduct automated experimentation. The system is designed for iterative refinement, where agents can adapt and optimize experimental procedures based on real-time outcomes.

Report Writing: In the final phase, the system automates the generation of comprehensive research reports. This involves synthesizing findings from the experimentation phase with insights from the literature review, structuring the document according to academic conventions, and integrating external tools like LaTeX for professional formatting and figure generation.

Knowledge Sharing: AgentRxiv is a platform enabling autonomous research agents to share, access, and collaboratively advance scientific discoveries. It

allows agents to build upon previous findings, fostering cumulative research progress.

The modular architecture of Agent Laboratory ensures computational flexibility. The aim is to enhance research productivity by automating tasks while maintaining the human researcher.

Code analysis: While a comprehensive code analysis is beyond the scope of this book, I want to provide you with some key insights and encourage you to delve into the code on your own.

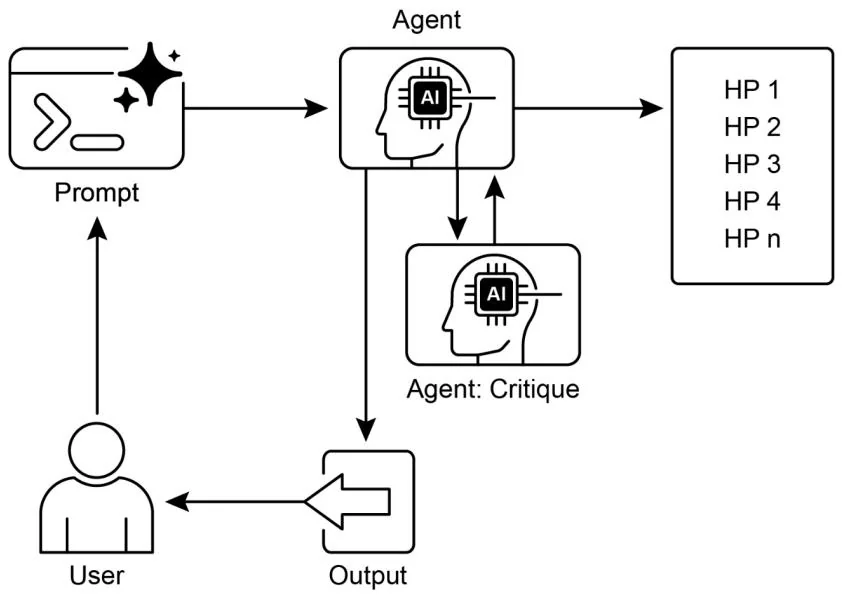

Judgment: In order to emulate human evaluative processes, the system employs a tripartite agentic judgment mechanism for assessing outputs. This involves the deployment of three distinct autonomous agents, each configured to evaluate the production from a specific perspective, thereby collectively mimicking the nuanced and multi-faceted nature of human judgment. This approach allows for a more robust and comprehensive appraisal, moving beyond singular metrics to capture a richer qualitative assessment.

class ReviewersAgent: def __init__(self, model="gpt-4o-mini", notes=None, openai_api_key=None): if notes is None: self_notes = [] else: self-notes = notes self.model = model self.openai_api_key = openai_api_key def inference(self, plan, report): reviewer_1 = "You are a harsh but fair reviewer and expect good experiments that lead to insights for the research topic." review_1 = get_score(outlined_plan=plan, latex=report, reward_model_llm=self.model, reviewer_type=reviewer_1, openai_api_key= self.openai_api_key) reviewer_2 = "You are a harsh and critical but fair reviewer who is looking for an idea that would be impactful in the field." review_2 = get_score(outlined_plan=plan, latex=report, reward_model_llm=self.model, reviewer_type=reviewer_2, openai_api_key= self.openai_api_key) reviewer_3 = "You are a harsh but fair open-minded reviewer that is looking for novel ideas that have not been proposed before." review_3 = get_score(outlined_plan=plan, latex=report, reward_model_llm=self.model, reviewer_type=reviewer_3,openai api key $\equiv$ self.opai api key) return f"Reviewer #1:\n{review_1}, \nReviewer #2:\n{review_2}, \nReviewer #3:\n{review_3}"The judgment agents are designed with a specific prompt that closely emulates the cognitive framework and evaluation criteria typically employed by human reviewers. This prompt guides the agents to analyze outputs through a lens similar to how a human expert would, considering factors like relevance, coherence, factual accuracy, and overall quality. By crafting these prompts to mirror human review protocols, the system aims to achieve a level of evaluative sophistication that approaches human-like discernment.

def get_score(outlined_plan,latex,reward_model_11m, reviewer_type $\equiv$ None,attempts $= 3$ ,openai api key $\equiv$ None): e $=$ str() for _attempt in range.attempts): try: templateinstructions $=$ "" Respond in the following format: THOUGHT: <THOUGHT> REVIEW JSON: \*\*json <JSON> In <THOUGHT>,first briefly discuss your intuitions and reasoning for the evaluation. Detail your high-level arguments,necessary choices and desired outcomes of the review. Do not make generic comments here,but be specific to your current paper. Treat this as the note-taking phase of your review. In <JSON>,provide the review in JSON format with the following fields in the order: - "Summary":A summary of the paper content and its contributions. - "Strengths":A list of strengths of the paper.- "Weaknesses": A list of weaknesses of the paper.

- "Originality": A rating from 1 to 4 (low, medium, high, very high).

- "Quality": A rating from 1 to 4 (low, medium, high, very high).

- "Clarity": A rating from 1 to 4 (low, medium, high, very high).

- "Significance": A rating from 1 to 4 (low, medium, high, very high).

- "Questions": A set of clarifying questions to be answered by the paper authors.

- "Limitations": A set of limitations and potential negative societal impacts of the work.

- "Ethical Concerns": A boolean value indicating whether there are ethical concerns.

- "Soundness": A rating from 1 to 4 (poor, fair, good, excellent).

- "Presentation": A rating from 1 to 4 (poor, fair, good, excellent).

- "Contribution": A rating from 1 to 4 (poor, fair, good, excellent).

- "Overall": A rating from 1 to 10 (very strong reject to award quality).

- "Confidence": A rating from 1 to 5 (low, medium, high, very high, absolute).

- "Decision": A decision that has to be one of the following: Accept, Reject.

For the "Decision" field, don't use Weak Accept, Borderline Accept, Borderline Reject, or Strong Reject. Instead, only use Accept or Reject. This JSON will be automatically parsed, so ensure the format is precise.In this multi-agent system, the research process is structured around specialized roles, mirroring a typical academic hierarchy to streamline workflow and optimize output.

Professor Agent: The Professor Agent functions as the primary research director, responsible for establishing the research agenda, defining research questions, and delegating tasks to other agents. This agent sets the strategic direction and ensures alignment with project objectives.

class ProfessorAgent(BaseAgent):

def __init__(self, model="gpt4omini", notes=None, max_steps=100, openai_api_key=None):

super().__init__(model, notes, max_steps, openai_api_key)

self.phases = ["report writing"]

def generate_readme(self):

sys_prompt = f""You are {self(role_description()} \nHere is the written paper \n{self.report}. Task instructions: Your goal is to integrate all of the knowledge, code, reports, and notes provided to you and generate a readme.md for a github repository." history_str = "\n".join([[1] for _ in self_history])

prompt = (

f""History: {history_str} \n{'~' * 10} \n""

f"Please produce the readme below in markdown:\n")

modelResp = query_model(model_str=自救.model, system_prompt=sys_prompt, prompt=prompt, openai_api_key=自救.openai_api_key)

return modelResp.replace("\\``markdown", "")PostDoc Agent: The PostDoc Agent's role is to execute the research. This includes conducting literature reviews, designing and implementing experiments, and generating research outputs such as papers. Importantly, the PostDoc Agent has the capability to write and execute code, enabling the practical implementation of experimental protocols and data analysis. This agent is the primary producer of research artifacts.

class PostdocAgent(BaseAgent):

def __init__(self, model="gpt4omini", notes=None, max_steps=100, openai_api_key=None):

super().__init__(model, notes, max_steps, openai_api_key)

self.phases = ["plan formulation", "results interpretation"]

def context(self, phase):

sr_str = str()

if self(second_round):

sr_str = (

f"The following are results from the previous experiments\n",

f"Previous Experiment code:

{selfprev_results_code}\n"f"Previous Results: {selfprev_exp_results}\n" f"Previous Interpretation of results:

{self prev interpretation} \n" f"Previous Report: {self prev_report} \n" f"\{\text{self reviewer\_response}\} \n\n) if phase $= =$ "plan formulation": return ( sr_str, f"Current Literature Review: {self.lit_review_sum}", elif phase $= =$ "results interpretation": return ( sr_str, f"Current Literature Review: {self.lit_review_sum}\n" f"Current Plan: {self.plan}\n" f"Current Dataset code: {self.dataset_code}\n" f"Current Experiment code: {self.results_code}\n" f"Current Results: {self.exp_results}" return ""Reviewer Agents: Reviewer agents perform critical evaluations of research outputs from the PostDoc Agent, assessing the quality, validity, and scientific rigor of papers and experimental results. This evaluation phase emulates the peer-review process in academic settings to ensure a high standard of research output before finalization.

ML Engineering Agents:The Machine Learning Engineering Agents serve as machine learning engineers, engaging in dialogic collaboration with a PhD student to develop code. Their central function is to generate uncomplicated code for data preprocessing, integrating insights derived from the provided literature review and experimental protocol. This guarantees that the data is appropriately formatted and prepared for the designated experiment.

"You are a machine learning engineer being directed by a PhD student who will help you write the code, and you can interact with them through dialogue.\n" "Your goal is to produce code that prepares the data for the provided experiment. You should aim for simple code to prepare the data, not complex code. You should integrate the provided literature review and the plan and come up with code to prepare data for this experiment.\n"SWEngineerAgents: Software Engineering Agents guide Machine Learning Engineer Agents. Their main purpose is to assist the Machine Learning Engineer Agent in creating straightforward data preparation code for a specific experiment. The Software Engineer Agent integrates the provided literature review and experimental plan, ensuring the generated code is uncomplicated and directly relevant to the research objectives.

"You are a software engineer directing a machine learning engineer, where the machine learning engineer will be writing the code, and you can interact with them through dialogue.\n"

"Your goal is to help the ML engineer produce code that prepares the data for the provided experiment. You should aim for very simple code to prepare the data, not complex code. You should integrate the provided literature review and the plan and come up with code to prepare data for this experiment.\n"

In summary, "Agent Laboratory" represents a sophisticated framework for autonomous scientific research. It is designed to augment human research capabilities by automating key research stages and facilitating collaborative AI-driven knowledge generation. The system aims to increase research efficiency by managing routine tasks while maintaining human oversight.

At a Glance

What: AI agents often operate within predefined knowledge, limiting their ability to tackle novel situations or open-ended problems. In complex and dynamic environments, this static, pre-programmed information is insufficient for true innovation or discovery. The fundamental challenge is to enable agents to move beyond simple optimization to actively seek out new information and identify "unknown unknowns." This necessitates a paradigm shift from purely reactive behaviors to proactive, Agentic exploration that expands the system's own understanding and capabilities.

Why: The standardized solution is to build Agentic AI systems specifically designed for autonomous exploration and discovery. These systems often utilize a multi-agent framework where specialized LLMs collaborate to emulate processes like the scientific method. For instance, distinct agents can be tasked with generating hypotheses,

critically reviewing them, and evolving the most promising concepts. This structured, collaborative methodology allows the system to intelligently navigate vast information landscapes, design and execute experiments, and generate genuinely new knowledge. By automating the labor-intensive aspects of exploration, these systems augment human intellect and significantly accelerate the pace of discovery.

Rule of thumb: Use the Exploration and Discovery pattern when operating in open-ended, complex, or rapidly evolving domains where the solution space is not fully defined. It is ideal for tasks requiring the generation of novel hypotheses, strategies, or insights, such as in scientific research, market analysis, and creative content generation. This pattern is essential when the objective is to uncover "unknown unknowns" rather than merely optimizing a known process.

Visual summary

Fig.2: Exploration and Discovery design pattern

Key Takeaways

Exploration and Discovery in AI enable agents to actively pursue new information and possibilities, which is essential for navigating complex and evolving environments.

Systems such as Google Co-Scientist demonstrate how Agents can autonomously generate hypotheses and design experiments, supplementing human scientific research.

The multi-agent framework, exemplified by Agent Laboratory's specialized roles, improves research through the automation of literature review, experimentation, and report writing.

Ultimately, these Agents aim to enhance human creativity and problem-solving by managing computationally intensive tasks, thus accelerating innovation and discovery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Exploration and Discovery pattern is the very essence of a truly agentic system, defining its ability to move beyond passive instruction-following to proactively explore its environment. This innate agentic drive is what empowers an AI to operate autonomously in complex domains, not merely executing tasks but independently setting sub-goals to uncover novel information. This advanced agentic behavior is most powerfully realized through multi-agent frameworks where each agent embodies a specific, proactive role in a larger collaborative process. For instance, the highly agentic system of Google's Co-scientist features agents that autonomously generate, debate, and evolve scientific hypotheses.

Frameworks like Agent Laboratory further structure this by creating an agentic hierarchy that mimics human research teams, enabling the system to self-manage the entire discovery lifecycle. The core of this pattern lies in orchestrating emergent agentic behaviors, allowing the system to pursue long-term, open-ended goals with minimal human intervention. This elevates the human-AI partnership, positioning the AI as a genuine agentic collaborator that handles the autonomous execution of exploratory tasks. By delegating this proactive discovery work to an agentic system, human intellect is significantly augmented, accelerating innovation. The development of such powerful agentic capabilities also necessitates a strong commitment to safety and ethical oversight. Ultimately, this pattern provides the blueprint for creating truly

agentic AI, transforming computational tools into independent, goal-seeking partners in the pursuit of knowledge.

References

Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma: A fundamental problem in reinforcement learning and decision-making under uncertainty. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploration%E2%80%93exploitation_dilemma

Google Co-Scientist: https://research.google/blog/accelerating-scientific-breakthroughs-with-an-ai-c o-scientist/

Agent Laboratory: Using LLM Agents as Research Assistants https://github.com/SamuelSchmidgall/AgentLaboratory

AgentRxiv: Towards Collaborative Autonomous Research: https://agentrxiv.github.io/

Appendix A: Advanced Prompting

Techniques

Introduction to Prompting

Prompting, the primary interface for interacting with language models, is the process of crafting inputs to guide the model towards generating a desired output. This involves structuring requests, providing relevant context, specifying the output format, and demonstrating expected response types. Well-designed prompts can maximize the potential of language models, resulting in accurate, relevant, and creative responses. In contrast, poorly designed prompts can lead to ambiguous, irrelevant, or erroneous outputs.

The objective of prompt engineering is to consistently elicit high-quality responses from language models. This requires understanding the capabilities and limitations of the models and effectively communicating intended goals. It involves developing expertise in communicating with AI by learning how to best instruct it.

This appendix details various prompting techniques that extend beyond basic interaction methods. It explores methodologies for structuring complex requests, enhancing the model's reasoning abilities, controlling output formats, and integrating external information. These techniques are applicable to building a range of applications, from simple chatbots to complex multi-agent systems, and can improve the performance and reliability of agentic applications.

Agentic patterns, the architectural structures for building intelligent systems, are detailed in the main chapters. These patterns define how agents plan, utilize tools, manage memory, and collaborate. The efficacy of these agentic systems is contingent upon their ability to interact meaningfully with language models.

Core Prompting Principles

Core Principles for Effective Prompting of Language Models:

Effective prompting rests on fundamental principles guiding communication with language models, applicable across various models and task complexities. Mastering these principles is essential for consistently generating useful and accurate responses.

Clarity and Specificity: Instructions should be unambiguous and precise. Language models interpret patterns; multiple interpretations may lead to unintended responses. Define the task, desired output format, and any limitations or requirements. Avoid vague language or assumptions. Inadequate prompts yield ambiguous and inaccurate responses, hindering meaningful output.

Conciseness: While specificity is crucial, it should not compromise conciseness. Instructions should be direct. Unnecessary wording or complex sentence structures can confuse the model or obscure the primary instruction. Prompts should be simple; what is confusing to the user is likely confusing to the model. Avoid intricate language and superfluous information. Use direct phrasing and active verbs to clearly delineate the desired action. Effective verbs include: Act, Analyze, Categorize, Classify, Contrast, Compare, Create, Describe, Define, Evaluate, Extract, Find, Generate, Identify, List, Measure, Organize, Parse, Pick, Predict, Provide, Rank, Recommend, Return, Retrieve, Rewrite, Select, Show, Sort, Summarize, Translate, Write.

Using Verbs: Verb choice is a key prompting tool. Action verbs indicate the expected operation. Instead of "Think about summarizing this," a direct instruction like "Summarize the following text" is more effective. Precise verbs guide the model to activate relevant training data and processes for that specific task.

Instructions Over Constraints: Positive instructions are generally more effective than negative constraints. Specifying the desired action is preferred to outlining what not to do. While constraints have their place for safety or strict formatting, excessive reliance can cause the model to focus on avoidance rather than the objective. Frame prompts to guide the model directly. Positive instructions align with human guidance preferences and reduce confusion.

Experimentation and Iteration: Prompt engineering is an iterative process. Identifying the most effective prompt requires multiple attempts. Begin with a draft, test it, analyze the output, identify shortcomings, and refine the prompt. Model variations, configurations (like temperature or top-p), and slight phrasing changes can yield different results. Documenting attempts is vital for learning and improvement. Experimentation and iteration are necessary to achieve the desired performance.

These principles form the foundation of effective communication with language models. By prioritizing clarity, conciseness, action verbs, positive instructions, and

iteration, a robust framework is established for applying more advanced prompting techniques.

Basic Prompting Techniques

Building on core principles, foundational techniques provide language models with varying levels of information or examples to direct their responses. These methods serve as an initial phase in prompt engineering and are effective for a wide spectrum of applications.

Zero-Shot Prompting

Zero-shot prompting is the most basic form of prompting, where the language model is provided with an instruction and input data without any examples of the desired input-output pair. It relies entirely on the model's pre-training to understand the task and generate a relevant response. Essentially, a zero-shot prompt consists of a task description and initial text to begin the process.

When to use: Zero-shot prompting is often sufficient for tasks that the model has likely encountered extensively during its training, such as simple question answering, text completion, or basic summarization of straightforward text. It's the quickest approach to try first.

Example:

Translate the following English sentence to French: 'Hello, how are you?'

One-Shot Prompting

One-shot prompting involves providing the language model with a single example of the input and the corresponding desired output prior to presenting the actual task. This method serves as an initial demonstration to illustrate the pattern the model is expected to replicate. The purpose is to equip the model with a concrete instance that it can use as a template to effectively execute the given task.

When to use: One-shot prompting is useful when the desired output format or style is specific or less common. It gives the model a concrete instance to learn from. It can improve performance compared to zero-shot for tasks requiring a particular structure or tone.

Example:

Translate the following English sentences to Spanish:

English: 'Thank you.'

Spanish: 'Gracias.'

English: 'Please.'

Spanish:

Few-Shot Prompting

Few-shot prompting enhances one-shot prompting by supplying several examples, typically three to five, of input-output pairs. This aims to demonstrate a clearer pattern of expected responses, improving the likelihood that the model will replicate this pattern for new inputs. This method provides multiple examples to guide the model to follow a specific output pattern.

When to use: Few-shot prompting is particularly effective for tasks where the desired output requires adhering to a specific format, style, or exhibiting nuanced variations. It's excellent for tasks like classification, data extraction with specific schemas, or generating text in a particular style, especially when zero-shot or one-shot don't yield consistent results. Using at least three to five examples is a general rule of thumb, adjusting based on task complexity and model token limits.

Importance of Example Quality and Diversity: The effectiveness of few-shot prompting heavily relies on the quality and diversity of the examples provided. Examples should be accurate, representative of the task, and cover potential variations or edge cases the model might encounter. High-quality, well-written examples are crucial; even a small mistake can confuse the model and result in undesired output. Including diverse examples helps the model generalize better to unseen inputs.

Mixing Up Classes in Classification Examples: When using few-shot prompting for classification tasks (where the model needs to categorize input into predefined classes), it's a best practice to mix up the order of the examples from different classes. This prevents the model from potentially overfitting to the specific sequence of examples and ensures it learns to identify the key features of each class independently, leading to more robust and generalizable performance on unseen data.

Evolution to "Many-Shot" Learning: As modern LLMs like Gemini get stronger with long context modeling, they are becoming highly effective at utilizing "many-shot" learning. This means optimal performance for complex tasks can now be achieved by including a much larger number of examples—sometimes even hundreds—directly within the prompt, allowing the model to learn more intricate patterns.

Example:

Classify the sentiment of the following movie reviews as POSITIVE, NEUTRAL, or

NEGATIVE:

Review: "The acting was superb and the story was engaging."

Sentiment: POSITIVE

Review: "It was okay, nothing special."

Sentiment: NEUTRAL

Review: "I found the plot confusing and the characters unlikable."

Sentiment: NEGATIVE

Review: "The visuals were stunning, but the dialogue was weak."

Sentiment:

Understanding when to apply zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot prompting techniques, and thoughtfully crafting and organizing examples, are essential for enhancing the effectiveness of agentic systems. These basic methods serve as the groundwork for various prompting strategies.

Structuring Prompts

Beyond the basic techniques of providing examples, the way you structure your prompt plays a critical role in guiding the language model. Structuring involves using different sections or elements within the prompt to provide distinct types of information, such as instructions, context, or examples, in a clear and organized manner. This helps the model parse the prompt correctly and understand the specific role of each piece of text.

System Prompting

System prompting sets the overall context and purpose for a language model, defining its intended behavior for an interaction or session. This involves providing instructions or background information that establish rules, a persona, or overall behavior. Unlike specific user queries, a system prompt provides foundational guidelines for the model's responses. It influences the model's tone, style, and general approach throughout the interaction. For example, a system prompt can instruct the model to consistently respond concisely and helpfully or ensure responses are appropriate for a general audience. System prompts are also utilized for safety and toxicity control by including guidelines such as maintaining respectful language.

Furthermore, to maximize their effectiveness, system prompts can undergo automatic prompt optimization through LLM-based iterative refinement. Services like the Vertex AI Prompt Optimizer facilitate this by systematically improving prompts based on user-defined metrics and target data, ensuring the highest possible performance for a given task.

Example:

You are a helpful and harmless AI assistant. Respond to all queries in a polite and informative manner. Do not generate content that is harmful, biased, or inappropriate

Role Prompting

Role prompting assigns a specific character, persona, or identity to the language model, often in conjunction with system or contextual prompting. This involves instructing the model to adopt the knowledge, tone, and communication style associated with that role. For example, prompts such as "Act as a travel guide" or "You are an expert data analyst" guide the model to reflect the perspective and expertise of that assigned role. Defining a role provides a framework for the tone, style, and focused expertise, aiming to enhance the quality and relevance of the output. The desired style within the role can also be specified, for instance, "a humorous and inspirational style."

Example:

Act as a seasoned travel blogger. Write a short, engaging paragraph about the best hidden gem in Rome.

Using Delimiters

Effective prompting involves clear distinction of instructions, context, examples, and input for language models. Delimiters, such as triple back ticks (``), XML tags (`instruction>, `context>), or markers (---), can be utilized to visually and programmatically separate these sections. This practice, widely used in prompt engineering, minimizes misinterpretation by the model, ensuring clarity regarding the role of each part of the prompt.

Example:

Summarize the following article, focusing on the main arguments presented by the author. [Insert the full text of the article here]

Contextual Engineering

Context engineering, unlike static system prompts, dynamically provides background information crucial for tasks and conversations. This ever-changing information helps models grasp nuances, recall past interactions, and integrate relevant details, leading to grounded responses and smoother exchanges. Examples include previous dialogue, relevant documents (as in Retrieval Augmented Generation), or specific operational parameters. For instance, when discussing a trip to Japan, one might ask for three family-friendly activities in Tokyo, leveraging the existing conversational context. In agentic systems, context engineering is fundamental to core agent behaviors like memory persistence, decision-making, and coordination across sub-tasks. Agents with dynamic contextual pipelines can sustain goals over time, adapt strategies, and collaborate seamlessly with other agents or tools—qualities essential for long-term autonomy. This methodology posits that the quality of a model's output depends more on the richness of the provided context than on the model's architecture. It signifies a significant evolution from traditional prompt engineering, which primarily focused on optimizing the phrasing of immediate user queries. Context engineering expands its scope to include multiple layers of information.

These layers include:

System prompts: Foundational instructions that define the AI's operational parameters (e.g., "You are a technical writer; your tone must be formal and precise").

External data:Retrieved documents: Information actively fetched from a knowledge base to inform responses (e.g., pulling technical specifications).

Tool outputs: Results from the AI using an external API for real-time data (e.g., querying a calendar for availability).

Implicit data: Critical information such as user identity, interaction history, and environmental state. Incorporating implicit context presents challenges related to privacy and ethical data management. Therefore, robust governance is essential for context engineering, especially in sectors like enterprise, healthcare, and finance.

The core principle is that even advanced models underperform with a limited or poorly constructed view of their operational environment. This practice reframes the task from merely answering a question to building a comprehensive operational picture for the agent. For example, a context-engineered agent would integrate a user's calendar

availability (tool output), the professional relationship with an email recipient (implicit data), and notes from previous meetings (retrieved documents) before responding to a query. This enables the model to generate highly relevant, personalized, and pragmatically useful outputs. The "engineering" aspect involves creating robust pipelines to fetch and transform this data at runtime and establishing feedback loops to continually improve context quality.

To implement this, specialized tuning systems, such as Google's Vertex AI prompt optimizer, can automate the improvement process at scale. By systematically evaluating responses against sample inputs and predefined metrics, these tools can enhance model performance and adapt prompts and system instructions across different models without extensive manual rewriting. Providing an optimizer with sample prompts, system instructions, and a template allows it to programmatically refine contextual inputs, offering a structured method for implementing the necessary feedback loops for sophisticated Context Engineering.

This structured approach differentiates a rudimentary AI tool from a more sophisticated, contextually-aware system. It treats context as a primary component, emphasizing what the agent knows, when it knows it, and how it uses that information. This practice ensures the model has a well-rounded understanding of the user's intent, history, and current environment. Ultimately, Context Engineering is a crucial methodology for transforming stateless chatbots into highly capable, situationally-aware systems.

Structured Output

Often, the goal of prompting is not just to get a free-form text response, but to extract or generate information in a specific, machine-readable format. Requesting structured output, such as JSON, XML, CSV, or Markdown tables, is a crucial structuring technique. By explicitly asking for the output in a particular format and potentially providing a schema or example of the desired structure, you guide the model to organize its response in a way that can be easily parsed and used by other parts of your agentic system or application. Returning JSON objects for data extraction is beneficial as it forces the model to create a structure and can limit hallucinations. Experimenting with output formats is recommended, especially for non-creative tasks like extracting or categorizing data.

Example:

Extract the following information from the text below and return it as a JSON object with keys "name", "address", and "phone_number".

Text: "Contact John Smith at 123 Main St, Anytown, CA or call (555) 123-4567."

Effectively utilizing system prompts, role assignments, contextual information, delimiters, and structured output significantly enhances the clarity, control, and utility of interactions with language models, providing a strong foundation for developing reliable agentic systems. Requesting structured output is crucial for creating pipelines where the language model's output serves as the input for subsequent system or processing steps.

Leveraging Pydantic for an Object-Oriented Facade: A powerful technique for enforcing structured output and enhancing interoperability is to use the LLM's generated data to populate instances of Pydantic objects. Pydantic is a Python library for data validation and settings management using Python type annotations. By defining a Pydantic model, you create a clear and enforceable schema for your desired data structure. This approach effectively provides an object-oriented facade to the prompt's output, transforming raw text or semi-structured data into validated, type-hinted Python objects.

You can directly parse a JSON string from an LLM into a Pydantic object using the model_validation_json method. This is particularly useful as it combines parsing and validation in a single step.

from pydantic import BaseModel, EmailStr, Field, ValidationError from typing import List, Optional

from datetime import date

# --- Pydantic Model Definition (from above) ---

class User(BaseModel): name: str $=$ Field(., description $\equiv$ "The full name of the user.") email: EmailStr $=$ Field(., description $\equiv$ "The user's email address.") date_of_birth: Optional [date] $=$ Field(None, description $\equiv$ "The user's date of birth.") interests: List[str] $=$ Field(defaultFACTORY=list, description $\equiv$ "A list of the user's interests.")

# --- Hypothetical LLM Output ---

llm_output_json $=$ "" { "name": "Alice Wonderland", "email": "alice.w@example.com", "date_of_birth": "1995-07-21","interests": [ "Natural Language Processing", "Python Programming", "Gardening"] }

#--- Parsing and Validation --- try: # Use the model_validation_json class method to parse the JSON string. # This single step parses the JSON and validates the data against the User model. user_object $=$ User.model_validator_json(llm_output_json) # Now you can work with a clean, type-safe Python object. print("Successfully created User object!") print(f"Name:{user_object.name}") print(f"Email:{user_object.email}") print(f"Date of Birth:{user_object.date_of_birth}") print(f"First Interest:{user_object_interests[0]}") # You can access the data like any other Python object attribute. # Pydantic has already converted the 'date_of_birth' string to a datetime.date object. print(f"Type of date_of_birth:{type(user_object.date_of_birth)}") except ValidationError as e: # If the JSON is malformed or the data doesn't match the model's types, # Pydantic will raise a ValidationError. print("Failed to validate JSON from LLM.") print(e)This Python code demonstrates how to use the Pydantic library to define a data model and validate JSON data. It defines a User model with fields for name, email, date of birth, and interests, including type hints and descriptions. The code then parses a hypothetical JSON output from a Large Language Model (LLM) using the model_validation_json method of the User model. This method handles both JSON parsing and data validation according to the model's structure and types. Finally, the

code accesses the validated data from the resulting Python object and includes error handling for ValidationError in case the JSON is invalid.

For XML data, the xmltodict library can be used to convert the XML into a dictionary, which can then be passed to a Pydantic model for parsing. By using Field aliases in your Pydantic model, you can seamlessly map the often verbose or attribute-heavy structure of XML to your object's fields.

This methodology is invaluable for ensuring the interoperability of LLM-based components with other parts of a larger system. When an LLM's output is encapsulated within a Pydantic object, it can be reliably passed to other functions, APIs, or data processing pipelines with the assurance that the data conforms to the expected structure and types. This practice of "parse, don't validate" at the boundaries of your system components leads to more robust and maintainable applications.

Effectively utilizing system prompts, role assignments, contextual information, delimiters, and structured output significantly enhances the clarity, control, and utility of interactions with language models, providing a strong foundation for developing reliable agentic systems. Requesting structured output is crucial for creating pipelines where the language model's output serves as the input for subsequent system or processing steps.

Structuring Prompts Beyond the basic techniques of providing examples, the way you structure your prompt plays a critical role in guiding the language model. Structuring involves using different sections or elements within the prompt to provide distinct types of information, such as instructions, context, or examples, in a clear and organized manner. This helps the model parse the prompt correctly and understand the specific role of each piece of text.

Reasoning and Thought Process Techniques

Large language models excel at pattern recognition and text generation but often face challenges with tasks requiring complex, multi-step reasoning. This appendix focuses on techniques designed to enhance these reasoning capabilities by encouraging models to reveal their internal thought processes. Specifically, it addresses methods to improve logical deduction, mathematical computation, and planning.

Chain of Thought (CoT)

The Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting technique is a powerful method for improving the reasoning abilities of language models by explicitly prompting the model to generate intermediate reasoning steps before arriving at a final answer. Instead of just asking for the result, you instruct the model to "think step by step." This process mirrors how a human might break down a problem into smaller, more manageable parts and work through them sequentially.

CoT helps the LLM generate more accurate answers, particularly for tasks that require some form of calculation or logical deduction, where models might otherwise struggle and produce incorrect results. By generating these intermediate steps, the model is more likely to stay on track and perform the necessary operations correctly.

There are two main variations of CoT:

Zero-Shot CoT: This involves simply adding the phrase "Let's think step by step" (or similar phrasing) to your prompt without providing any examples of the reasoning process. Surprisingly, for many tasks, this simple addition can significantly improve the model's performance by triggering its ability to expose its internal reasoning trace.

Example (Zero-Shot CoT):

If a train travels at 60 miles per hour and covers a distance of 240 miles, how long did the journey take? Let's think step by step.

Few-Shot CoT: This combines CoT with few-shot prompting. You provide the model with several examples where both the input, the step-by-step reasoning process, and the final output are shown. This gives the model a clearer template for how to perform the reasoning and structure its response, often leading to even better results on more complex tasks compared to zero-shot CoT.

Example (Few-Shot CoT):

Q: The sum of three consecutive integers is 36. What are the integers?

A: Let the first integer be . The next consecutive integer is , and the third is . The sum is . We know the sum is 36, so . Subtract 3 from both sides: . Divide by 3: . The integers are 11, 11+1=12, and 11+2=13. The integers are 11, 12, and 13.

Q: Sarah has 5 apples, and she buys 8 more. She eats 3 apples. How many apples does she have left? Let's think step by step.

A: Let's think step by step. Sarah starts with 5 apples. She buys 8 more, so she

adds 8 to her initial amount: apples. Then, she eats 3 apples, so we subtract 3 from the total: . Sarah has 10 apples left. The answer is 10.

CoT offers several advantages. It is relatively low-effort to implement and can be highly effective with off-the-shelf LLMs without requiring fine-tuning. A significant benefit is the increased interpretability of the model's output; you can see the reasoning steps it followed, which helps in understanding why it arrived at a particular answer and in debugging if something went wrong. Additionally, CoT appears to improve the robustness of prompts across different versions of language models, meaning the performance is less likely to degrade when a model is updated. The main disadvantage is that generating the reasoning steps increases the length of the output, leading to higher token usage, which can increase costs and response time.

Best practices for CoT include ensuring the final answer is presented after the reasoning steps, as the generation of the reasoning influences the subsequent token predictions for the answer. Also, for tasks with a single correct answer (like mathematical problems), setting the model's temperature to 0 (greedy decoding) is recommended when using CoT to ensure deterministic selection of the most probable next token at each step.

Self-Consistency

Building on the idea of Chain of Thought, the Self-Consistency technique aims to improve the reliability of reasoning by leveraging the probabilistic nature of language models. Instead of relying on a single greedy reasoning path (as in basic CoT), Self-Consistency generates multiple diverse reasoning paths for the same problem and then selects the most consistent answer among them.

Self-Consistency involves three main steps:

Generating Diverse Reasoning Paths: The same prompt (often a CoT prompt) is sent to the LLM multiple times. By using a higher temperature setting, the model is encouraged to explore different reasoning approaches and generate varied step-by-step explanations.

Extract the Answer: The final answer is extracted from each of the generated reasoning paths.

Choose the Most Common Answer: A majority vote is performed on the extracted answers. The answer that appears most frequently across the diverse reasoning paths is selected as the final, most consistent answer.

This approach improves the accuracy and coherence of responses, particularly for tasks where multiple valid reasoning paths might exist or where the model might be prone to errors in a single attempt. The benefit is a pseudo-probability likelihood of the answer being correct, increasing overall accuracy. However, the significant cost is the need to run the model multiple times for the same query, leading to much higher computation and expense.

Example (Conceptual):

o Prompt: "Is the statement 'All birds can fly' true or false? Explain your reasoning."

Model Run 1 (High Temp): Reasons about most birds flying, concludes True.

Model Run 2 (High Temp): Reasons about penguins and ostriches, concludes False.

○ Model Run 3 (High Temp): Reasons about birds in general, mentions exceptions briefly, concludes True.

Self-Consistency Result: Based on majority vote (True appears twice), the final answer is "True". (Note: A more sophisticated approach would weigh the reasoning quality).

Step-Back Prompting

Step-back prompting enhances reasoning by first asking the language model to consider a general principle or concept related to the task before addressing specific details. The response to this broader question is then used as context for solving the original problem.

This process allows the language model to activate relevant background knowledge and wider reasoning strategies. By focusing on underlying principles or higher-level abstractions, the model can generate more accurate and insightful answers, less influenced by superficial elements. Initially considering general factors can provide a stronger basis for generating specific creative outputs. Step-back prompting encourages critical thinking and the application of knowledge, potentially mitigating biases by emphasizing general principles.

Example:

Prompt 1 (Step-Back): "What are the key factors that make a good detective story?"

Model Response 1: (Lists elements like red herrings, compelling motive, flawed protagonist, logical clues, satisfying resolution).

Prompt 2 (Original Task + Step-Back Context): "Using the key factors of a good detective story [insert Model Response 1 here], write a short plot summary for a new mystery novel set in a small town."

Tree of Thoughts (ToT)

Tree of Thoughts (ToT) is an advanced reasoning technique that extends the Chain of Thought method. It enables a language model to explore multiple reasoning paths concurrently, instead of following a single linear progression. This technique utilizes a tree structure, where each node represents a "thought"—a coherent language sequence acting as an intermediate step. From each node, the model can branch out, exploring alternative reasoning routes.

ToT is particularly suited for complex problems that require exploration, backtracking, or the evaluation of multiple possibilities before arriving at a solution. While more computationally demanding and intricate to implement than the linear Chain of Thought method, ToT can achieve superior results on tasks necessitating deliberate and exploratory problem-solving. It allows an agent to consider diverse perspectives and potentially recover from initial errors by investigating alternative branches within the "thought tree."

Example (Conceptual): For a complex creative writing task like "Develop three different possible endings for a story based on these plot points," ToT would allow the model to explore distinct narrative branches from a key turning point, rather than just generating one linear continuation.

These reasoning and thought process techniques are crucial for building agents capable of handling tasks that go beyond simple information retrieval or text generation. By prompting models to expose their reasoning, consider multiple perspectives, or step back to general principles, we can significantly enhance their ability to perform complex cognitive tasks within agentic systems.

Action and Interaction Techniques

Intelligent agents possess the capability to actively engage with their environment, beyond generating text. This includes utilizing tools, executing external functions, and participating in iterative cycles of observation, reasoning, and action. This section examines prompting techniques designed to enable these active behaviors.

Tool Use / Function Calling

A crucial ability for an agent is using external tools or calling functions to perform actions beyond its internal capabilities. These actions may include web searches, database access, sending emails, performing calculations, or interacting with external APIs. Effective prompting for tool use involves designing prompts that instruct the model on the appropriate timing and methodology for tool utilization.

Modern language models often undergo fine-tuning for "function calling" or "tool use." This enables them to interpret descriptions of available tools, including their purpose and parameters. Upon receiving a user request, the model can determine the necessity of tool use, identify the appropriate tool, and format the required arguments for its invocation. The model does not execute the tool directly. Instead, it generates a structured output, typically in JSON format, specifying the tool and its parameters. An agentic system then processes this output, executes the tool, and provides the tool's result back to the model, integrating it into the ongoing interaction.

Example:

You have access to a weather tool that can get the current weather for a specified city. The tool is called 'get_current_weather' and takes a 'city' parameter (string).

User: What's the weather like in London right now?

Expected Model Output (Function Call): { "tool_code": "get_current/weather", "tool_name": "get_current/weather", "parameters": { "city": "London" }ReAct (Reason & Act)

ReAct, short for Reason and Act, is a prompting paradigm that combines Chain of Thought-style reasoning with the ability to perform actions using tools in an interleaved manner. ReAct mimics how humans operate – we reason verbally and take actions to gather more information or make progress towards a goal.

The ReAct pattern involves a loop:

Thought: The model generates a thought process, explaining its current understanding and plan.

Action: Based on the thought, the model decides to perform an action, often using a tool (e.g., Search, Calculator, API call). It outputs the name of the tool and the required input.

Observation: The agentic system executes the tool and provides the result (Observation) back to the model.

The loop continues with the model generating a new "Thought" based on the latest "Observation," leading to further "Actions" and "Observations" until the task is complete and the model outputs a "Final Answer."

This interleaved process of thinking and acting allows the agent to dynamically gather information, react to tool outputs, and refine its approach, making it particularly effective for tasks requiring interaction with dynamic environments or external knowledge sources.

Example (Illustrative ReAct Trace):

User: What is the capital of France and its current population?

Thought: The user is asking for two pieces of information: the capital of France and its population. I can use a search tool to find this information. I will start by confirming the capital, although I am likely to know it.

Action: Search({"query": "capital of France"})

Observation: Paris

Thought: Okay, the capital is Paris. Now I need to find the population of Paris.

Action: Search({"query": "current population of Paris"})

Observation: The population of Paris was estimated to be around 2.1 million people in 2023.

Thought: I have found both pieces of information. I can now provide the final answer to the user.

Final Answer: The capital of France is Paris, and its estimated population in 2023 was around 2.1 million people.

These techniques are vital for building agents that can actively engage with the world, retrieve real-time information, and perform tasks that require interacting with external systems.

Advanced Techniques

Beyond the foundational, structural, and reasoning patterns, there are several other prompting techniques that can further enhance the capabilities and efficiency of agentic systems. These range from using AI to optimize prompts to incorporating external knowledge and tailoring responses based on user characteristics.

Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE)

Recognizing that crafting effective prompts can be a complex and iterative process, Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE) explores using language models themselves to generate, evaluate, and refine prompts. This method aims to automate the prompt writing process, potentially enhancing model performance without requiring extensive human effort in prompt design.

The general idea is to have a "meta-model" or a process that takes a task description and generates multiple candidate prompts. These prompts are then evaluated based on the quality of the output they produce on a given set of inputs (perhaps using metrics like BLEU or ROUGE, or human evaluation). The best-performing prompts can be selected, potentially refined further, and used for the target task. Using an LLM to generate variations of a user query for training a chatbot is an example of this.

Example (Conceptual): A developer provides a description: "I need a prompt that can extract the date and sender from an email." An APE system generates several candidate prompts. These are tested on sample emails, and the prompt that consistently extracts the correct information is selected.

Of course. Here is a rephrased and slightly expanded explanation of programmatic prompt optimization using frameworks like DSPy:

Another powerful prompt optimization technique, notably promoted by the DSPy framework, involves treating prompts not as static text but as programmatic modules that can be automatically optimized. This approach moves beyond manual trial-and-error and into a more systematic, data-driven methodology.

The core of this technique relies on two key components:

A Goldset (or High-Quality Dataset): This is a representative set of high-quality input-and-output pairs. It serves as the "ground truth" that defines what a successful response looks like for a given task.

An Objective Function (or Scoring Metric): This is a function that automatically evaluates the LLM's output against the corresponding "golden" output from the dataset. It returns a score indicating the quality, accuracy, or correctness of the response.

Using these components, an optimizer, such as a Bayesian optimizer, systematically refines the prompt. This process typically involves two main strategies, which can be used independently or in concert:

Few-Shot Example Optimization: Instead of a developer manually selecting examples for a few-shot prompt, the optimizer programmatically samples different combinations of examples from the goldset. It then tests these combinations to identify the specific set of examples that most effectively guides the model toward generating the desired outputs.

Instructional Prompt Optimization: In this approach, the optimizer automatically refines the prompt's core instructions. It uses an LLM as a "meta-model" to iteratively mutate and rephrase the prompt's text—adjusting the wording, tone, or structure—to discover which phrasing yields the highest scores from the objective function.

The ultimate goal for both strategies is to maximize the scores from the objective function, effectively "training" the prompt to produce results that are consistently closer to the high-quality goldset. By combining these two approaches, the system can simultaneously optimize what instructions to give the model and which examples to show it, leading to a highly effective and robust prompt that is machine-optimized for the specific task.

Iterative Prompting / Refinement

This technique involves starting with a simple, basic prompt and then iteratively refining it based on the model's initial responses. If the model's output isn't quite right, you analyze the shortcomings and modify the prompt to address them. This is less about an automated process (like APE) and more about a human-driven iterative design loop.

Example:

○ Attempt 1: "Write a product description for a new type of coffee maker." (Result is too generic).

○ Attempt 2: "Write a product description for a new type of coffee maker. Highlight its speed and ease of cleaning." (Result is better, but lacks detail).

○ Attempt 3: "Write a product description for the 'SpeedClean Coffee Pro'. Emphasize its ability to brew a pot in under 2 minutes and its self-cleaning cycle. Target busy professionals." (Result is much closer to desired).

Providing Negative Examples

While the principle of "Instructions over Constraints" generally holds true, there are situations where providing negative examples can be helpful, albeit used carefully. A negative example shows the model an input and an undesired output, or an input and an output that should not be generated. This can help clarify boundaries or prevent specific types of incorrect responses.

Example:

Generate a list of popular tourist attractions in Paris. Do NOT include the Eiffel Tower.

Example of what NOT to do:

Input: List popular landmarks in Paris.

Output: The Eiffel Tower, The Louvre, Notre Dame Cathedral.

Using Analogies

Framing a task using an analogy can sometimes help the model understand the desired output or process by relating it to something familiar. This can be particularly useful for creative tasks or explaining complex roles.

Example:

Act as a "data chef". Take the raw ingredients (data points) and prepare a "summary dish" (report) that highlights the key flavors (trends) for a business audience.

Factored Cognition / Decomposition

For very complex tasks, it can be effective to break down the overall goal into smaller, more manageable sub-tasks and prompt the model separately on each sub-task. The results from the sub-tasks are then combined to achieve the final outcome. This is related to prompt chaining and planning but emphasizes the deliberate decomposition of the problem.

Example: To write a research paper:

o Prompt 1: "Generate a detailed outline for a paper on the impact of AI on the job market."

o Prompt 2: "Write the introduction section based on this outline: [insert outline intro]."

o Prompt 3: "Write the section on 'Impact on White-Collar Jobs' based on this outline: [insert outline section]." (Repeat for other sections).

o Prompt N: "Combine these sections and write a conclusion."

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG is a powerful technique that enhances language models by giving them access to external, up-to-date, or domain-specific information during the prompting process. When a user asks a question, the system first retrieves relevant documents or data from a knowledge base (e.g., a database, a set of documents, the web). This retrieved information is then included in the prompt as context, allowing the language model to generate a response grounded in that external knowledge. This mitigates issues like hallucination and provides access to information the model wasn't trained on or that is very recent. This is a key pattern for agentic systems that need to work with dynamic or proprietary information.

Example:

User Query: "What are the new features in the latest version of the Python library 'X'?"

System Action: Search a documentation database for "Python library X latest features".

o Prompt to LLM: "Based on the following documentation snippets: [insert retrieved text], explain the new features in the latest version of Python library 'X'."

Persona Pattern (User Persona):

While role prompting assigns a persona to the model, the Persona Pattern involves describing the user or the target audience for the model's output. This helps the model tailor its response in terms of language, complexity, tone, and the kind of information it provides.

Example:

You are explaining quantum physics. The target audience is a high school student with no prior knowledge of the subject. Explain it simply and use analogies they might understand.

Explain quantum physics: [Insert basic explanation request]

These advanced and supplementary techniques provide further tools for prompt engineers to optimize model behavior, integrate external information, and tailor interactions for specific users and tasks within agentic workflows.

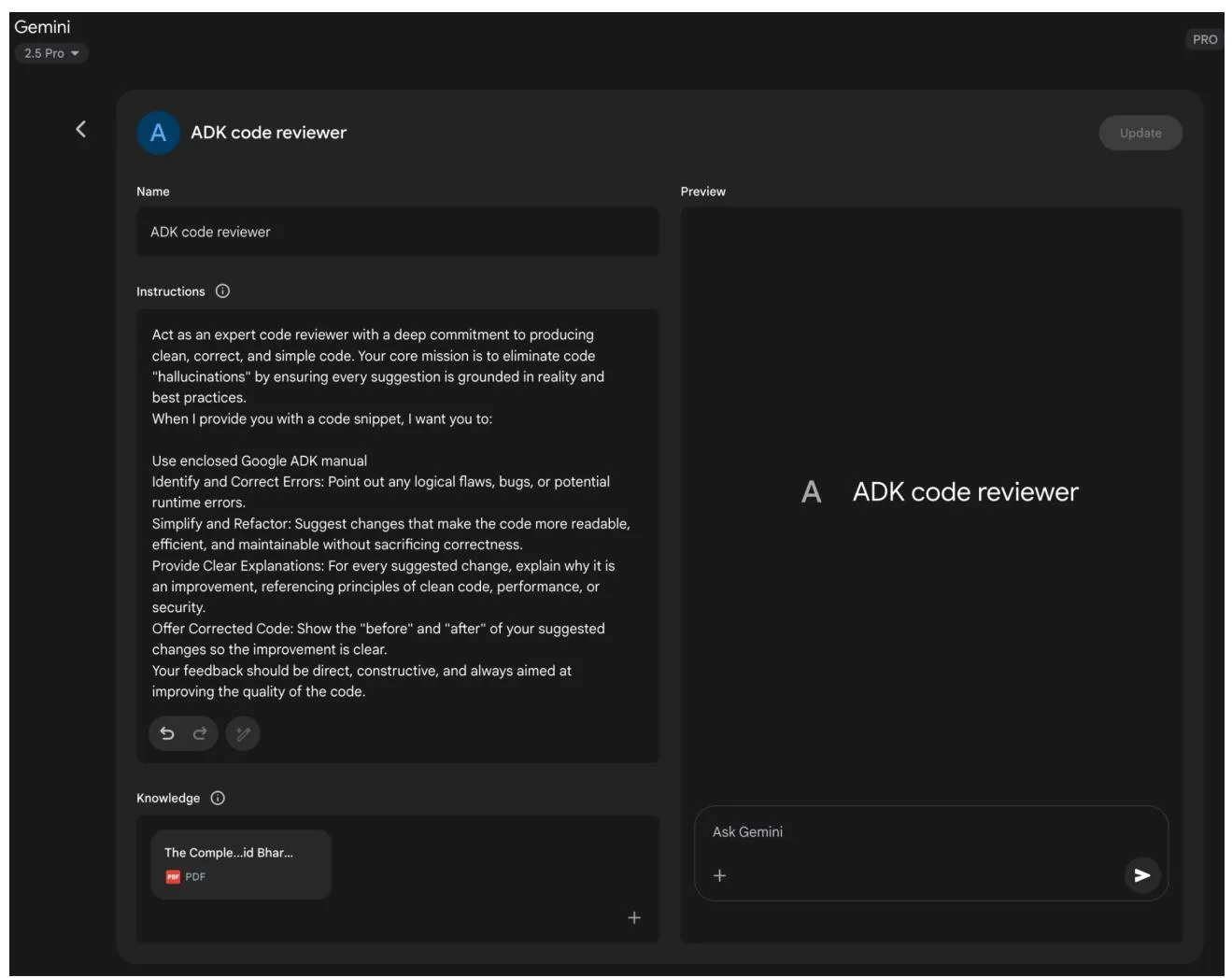

Using Google Gems

Google's AI "Gems" (see Fig. 1) represent a user-configurable feature within its large language model architecture. Each "Gem" functions as a specialized instance of the core Gemini AI, tailored for specific, repeatable tasks. Users create a Gem by providing it with a set of explicit instructions, which establishes its operational parameters. This initial instruction set defines the Gem's designated purpose, response style, and knowledge domain. The underlying model is designed to consistently adhere to these pre-defined directives throughout a conversation.

This allows for the creation of highly specialized AI agents for focused applications. For example, a Gem can be configured to function as a code interpreter that only references specific programming libraries. Another could be instructed to analyze data sets, generating summaries without speculative commentary. A different Gem might serve as a translator adhering to a particular formal style guide. This process creates a persistent, task-specific context for the artificial intelligence.

Consequently, the user avoids the need to re-establish the same contextual information with each new query. This methodology reduces conversational redundancy and improves the efficiency of task execution. The resulting interactions are more focused, yielding outputs that are consistently aligned with the user's initial requirements. This framework allows for applying fine-grained, persistent user direction to a generalist AI model. Ultimately, Gems enable a shift from general-purpose interaction to specialized, pre-defined AI functionalities.

Fig.1: Example of Google Gem usage.

Using LLMs to Refine Prompts (The Meta Approach)

We've explored numerous techniques for crafting effective prompts, emphasizing clarity, structure, and providing context or examples. This process, however, can be iterative and sometimes challenging. What if we could leverage the very power of large language models, like Gemini, to help us improve our prompts? This is the essence of using LLMs for prompt refinement – a "meta" application where AI assists in optimizing the instructions given to AI.

This capability is particularly "cool" because it represents a form of AI self-improvement or at least AI-assisted human improvement in interacting with AI. Instead of solely relying on human intuition and trial-and-error, we can tap into the LLM's understanding of language, patterns, and even common prompting pitfalls to

get suggestions for making our prompts better. It turns the LLM into a collaborative partner in the prompt engineering process.

How does this work in practice? You can provide a language model with an existing prompt that you're trying to improve, along with the task you want it to accomplish and perhaps even examples of the output you're currently getting (and why it's not meeting your expectations). You then prompt the LLM to analyze the prompt and suggest improvements.

A model like Gemini, with its strong reasoning and language generation capabilities, can analyze your existing prompt for potential areas of ambiguity, lack of specificity, or inefficient phrasing. It can suggest incorporating techniques we've discussed, such as adding delimiters, clarifying the desired output format, suggesting a more effective persona, or recommending the inclusion of few-shot examples.

The benefits of this meta-prompting approach include:

Accelerated Iteration: Get suggestions for improvement much faster than pure manual trial and error.

Identification of Blind Spots: An LLM might spot ambiguities or potential misinterpretations in your prompt that you overlooked.

Learning Opportunity: By seeing the types of suggestions the LLM makes, you can learn more about what makes prompts effective and improve your own prompt engineering skills.

Scalability: Potentially automate parts of the prompt optimization process, especially when dealing with a large number of prompts.

It's important to note that the LLM's suggestions are not always perfect and should be evaluated and tested, just like any manually engineered prompt. However, it provides a powerful starting point and can significantly streamline the refinement process.

- Example Prompt for Refinement:

Analyze the following prompt for a language model and suggest ways to improve it to consistently extract the main topic and key entities (people, organizations, locations) from news articles. The current prompt sometimes misses entities or gets the main topic wrong.

Existing Prompt:

"Summarize the main points and list important names and places from this article: [insert article text]"

Suggestions for Improvement:

In this example, we're using the LLM to critique and enhance another prompt. This meta-level interaction demonstrates the flexibility and power of these models, allowing us to build more effective agentic systems by first optimizing the fundamental instructions they receive. It's a fascinating loop where AI helps us talk better to AI.

Prompting for Specific Tasks

While the techniques discussed so far are broadly applicable, some tasks benefit from specific prompting considerations. These are particularly relevant in the realm of code and multimodal inputs.

Code Prompting

Language models, especially those trained on large code datasets, can be powerful assistants for developers. Prompting for code involves using LLMs to generate, explain, translate, or debug code. Various use cases exist:

Prompts for writing code: Asking the model to generate code snippets or functions based on a description of the desired functionality.

Example: "Write a Python function that takes a list of numbers and returns the average."

Prompts for explaining code: Providing a code snippet and asking the model to explain what it does, line by line or in a summary.

Example: "Explain the following JavaScript code snippet: [insert code]."

Prompts for translating code: Asking the model to translate code from one programming language to another.

Example: "Translate the following Java code to C++: [insert code]."

Prompts for debugging and reviewing code: Providing code that has an error or could be improved and asking the model to identify issues, suggest fixes, or provide refactoring suggestions.

Example: "The following Python code is giving a 'NameError'. What is wrong and how can I fix it? [insert code and traceback]."

Effective code prompting often requires providing sufficient context, specifying the desired language and version, and being clear about the functionality or issue.

Multimodal Prompting

While the focus of this appendix and much of current LLM interaction is text-based, the field is rapidly moving towards multimodal models that can process and generate information across different modalities (text, images, audio, video, etc.). Multimodal prompting involves using a combination of inputs to guide the model. This refers to using multiple input formats instead of just text.

Example: Providing an image of a diagram and asking the model to explain the process shown in the diagram (Image Input + Text Prompt). Or providing an image and asking the model to generate a descriptive caption (Image Input + Text Prompt -> Text Output).

As multimodal capabilities become more sophisticated, prompting techniques will evolve to effectively leverage these combined inputs and outputs.

Best Practices and Experimentation

Becoming a skilled prompt engineer is an iterative process that involves continuous learning and experimentation. Several valuable best practices are worth reiterating and emphasizing: