6.5_Concurrent_Copying_and_Kernel_Processing

6.5 Concurrent Copying and Kernel Processing

Since CUDA applications must transfer data across the PCI Express bus in order for the GPU to operate on it, another performance opportunity presents itself in the form of performing those host device memory transfers concurrently with

kernel processing. According to Amdahl's Law, the maximum speedup achievable by using multiple processors is

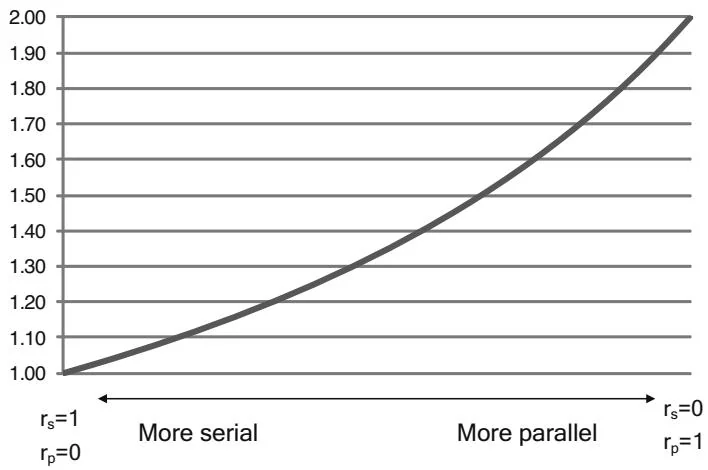

where and is the number of processors. In the case of concurrent copying and kernel processing, the "number of processors" is the number of autonomous hardware units in the GPU: one or two copy engines, plus the SMs that execute the kernels. For , Figure 6.6 shows the idealized speedup curve as and vary.

So in theory, a 2x performance improvement is possible on a GPU with one copy engine, but only if the program gets perfect overlap between the SMs and the copy engine, and only if the program spends equal time transferring and processing the data.

Before undertaking this endeavor, you should take a close look at whether it will benefit your application. Applications that are extremely transfer-bound (i.e., they spend most of their time transferring data to and from the GPU) or extremely compute-bound (i.e., they spend most of their time processing data on the GPU) will derive little benefit from overlapping transfer and compute.

Speedup Due to Parallelism,

Figure 6.6 Idealized Amdahl's Law curve.

6.5.1 CONCURRENTYCIMEMCPYKERNEL.CU

The program concurrencyMemcpyKernel.cu is designed to illustrate not only how to implement concurrent memcpy and kernel execution but also how to determine whether it is worth doing at all. Listing 6.3 gives a AddKernel(), a "makework" kernel that has a parameter cycles to control how long it runs.

Listing 6.3 AddKernel(), a makework kernel with parameterized computational density.

global void AddKernel( int \*out, const int \*in, size_t N, int addValue, int cycles) for (size_t i $=$ blockIdx.x\*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x; i $< \mathbb{N}$ . i $+=$ blockDim.x\*gridDim.x) volatile int value $=$ in[i]; for (int j $= 0$ ;j $<$ cycles; $j + +$ ){ value $+=$ addValue; } out[i] $=$ value;AddKernel() streams an array of integers from in to out, looping over each input value cycles times. By varying the value of cycles, we can make the kernel range from a trivial streaming kernel that pushes the memory bandwidth limits of the machine to a totally compute-bound kernel.

These two routines in the program measure the performance of AddKernel().

TimeSequentialMemcpyKernel() copies the input data to the GPU, invokes AddKernel(), and copies the output back from the GPU in separate, sequential steps.

TimeConcurrentOperations() allocates a number of CUDA streams and performs the host device memcpy, kernel processing, and device host memcpy in parallel.

TimeSequentialMemcpyKernel(), given in Listing 6.4, uses four CUDA events to separately time the host device memcpy, kernel processing, and

device→host memcpy. It also reports back the total time, as measured by the CUDA events.

Listing 6.4 TimeSequentialMemcpyKernel() function.

bool

TimeSequentialMemcpyKernel( float \*timesHtoD, float \*timesKernel, float \*timesDtoH, float \*timesTotal, size_t N, const chShmooRange& cyclesRange, int numBlocks)

{udaError_t status; bool ret $=$ false; int \*hostIn $= 0$ . int \*hostOut $= 0$ . int \*deviceIn $= 0$ . int \*deviceOut $= 0$ . const int numEvents $= 4$ .udaEvent_t events[numEvents]; for (int i $= 0$ ;i $<$ numEvents; $\mathrm{i + + }$ ) { events[i] $=$ NULL; CUDART_CHECK(cudaEventCreate(&events[i])); } CUDAAllocHost( &hostIn,N\*sizeof(int)); CUDAAllocHost( &hostOut,N\*sizeof(int)); CUDAAlloc( &deviceIn,N\*sizeof(int)); CUDAAlloc( &deviceOut,N\*sizeof(int)); for (size_t i $= 0$ ;i $<$ N; $\mathrm{i + + }$ ) { hostIn[i] $=$ rand(); } CUDADeviceSynchronize(); for (chShmooIterator cycles(cyclesRange); cycles; cycles++) { printf("."); fflush( stdout);udaEventRecord(evento[O],NULL);udaMemcpyAsync(deviceIn,hostIn,N\*sizeof(int),udaMempyHostToDevice, NULL);udaEventRecord(evento[1],NULL); AddKernel<<numBlocks,256>>>( deviceOut, deviceIn,N,0xcc,\*cycles);udaEventRecord(evento[2],NULL);udaMempyAsync(hostOut,deviceOut,N\*sizeof(int),udaMempyDeviceToHost, NULL);udaEventRecord(evento[3],NULL);cudaDeviceSynchronize();

cudaEventElapsedTime( timesHtoD, events[0], events[1]);

cudaEventElapsedTime( timesKernel, events[1], events[2]);

cudaEventElapsedTime( timesDtoH, events[2], events[3]);

cudaEventElapsedTime( timesTotal, events[0], events[3]);

timesHtoD += 1;

timesKernel += 1;

timesDtoH += 1;

timesTotal += 1;

}

ret = true;

Error: for ( int i = 0; i < numEvents; i++) {udaEventDestroy( events[i]); }udaFree( deviceIn );udaFree( deviceOut );udaFreeHost( hostOut );udaFreeHost( hostIn );return ret;The cyclesRange parameter, which uses the "shmoo" functionality described in Section A.4, specifies the range of cycles values to use when invoking AddKernel(). On a cg1.4xlarge instance in EC2, the times (in ms) for cycles values from 4..64 are as follows.

continues

For values of cycles around 48 (highlighted), where the kernel takes about the same amount of time as the memcpy operations, we presume there would be a benefit in performing the operations concurrently.

The routine TimeConcurrentMemcpyKernel() divides the computation performed by AddKernel() evenly into segments of size streamIncrement and uses a separate CUDA stream to compute each. The code fragment in Listing 6.5, from TimeConcurrentMemcpyKernel(), highlights the complexity of programming with streams.

Listing 6.5 TimeConcurrentMemcpyKernel() fragment.

intLeft $= \mathrm{N}$

for ( int stream $= 0$ ; stream $<$ numStreams; stream $+ +$ ){ size_t intsToDo $=$ (intsLeft < intsPerStream)? intsLeft : intsPerStream; CUDA_CHECK(udaMemcpyAsyncdeviceIn+stream\*intsPerStream, hostIn+stream\*intsPerStream, intsToDo\*sizeof(int),udaMempyHostToDevice,streams[stream])); intsLeft $= =$ intsToDo;

}intLeft $= \mathrm{N}$

for ( int stream $= 0$ ; stream $<$ numStreams; stream $+ +$ ){ size_tintsToDo $=$ (intsLeft $<$ intsPerStream)? intsLeft : intsPerStream; AddKernel<<numBlocks,256,0,streams[stream]>>>deviceOut+stream\*intsPerStream, deviceIn+stream\*intsPerStream, intsToDo,0xcc,\*cycles); intsLeft $= =$ intsToDo;

}

intsLeft $= \mathrm{N}$ .

for ( int stream $= 0$ ; stream $<$ numStreams; stream $+ +$ ){ size_tintsToDo $=$ (intsLeft $<$ intsPerStream)? intsLeft : intsPerStream; CUDArt_CHECK(udaMemcpyAsync(hostOut+stream\*intsPerStream, deviceOut+stream\*intsPerStream, intsToDo\*sizeof(int),udaMemcpyDeviceToHost,streams[stream])); intsLeft $= =$ intsToDo;

}Besides requiring the application to create and destroy CUDA streams, the streams must be looped over separately for each of the host→device memcpy, kernel processing, and device→host memcpy operations. Without this "software-pipelining," there would be no concurrent execution of the different streams' work, as each streamed operation is preceded by an "interlock" operation that prevents the operation from proceeding until the previous operation in that stream has completed. The result would be not only a failure to get parallel execution between the engines but also an additional performance degradation due to the slight overhead of managing stream concurrency.

The computation cannot be made fully concurrent, since no kernel processing can be overlapped with the first or last memcpy, and there is some overhead in synchronizing between CUDA streams and, as we saw in the previous section, in invoking the memcpy and kernel operations themselves. As a result, the optimal number of streams depends on the application and should be determined empirically. The concurrencyMemcpyKernel.cu program enables the number of streams to be specified on the command line using the --numStreams parameter.

6.5.2 PERFORMANCE RESULTS

The concurrencyMemcpyKernel.cu program generates a report on performance characteristics over a variety of cycles values, with a fixed buffer size and number of streams. On a cg1.4xlarge instance in Amazon EC2, with a buffer size of 128M integers and 8 streams, the report is as follows for cycles values from 4..64.

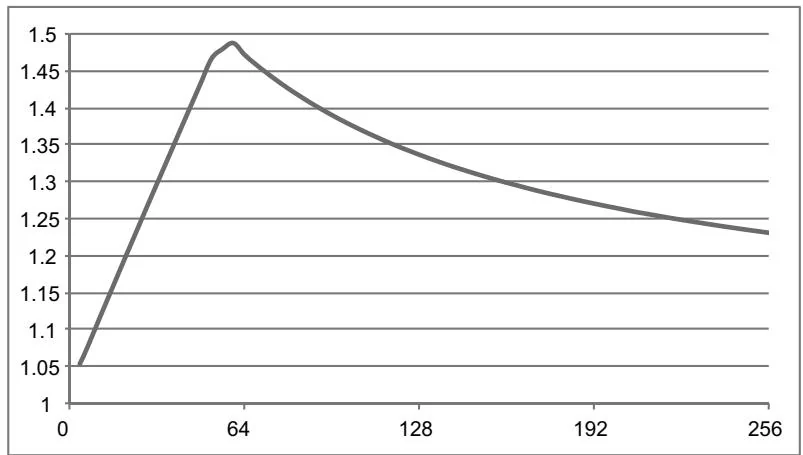

Figure 6.7 Speedup due memcpy/kernel concurrency (Tesla M2050).

The full graph for cycles values from 4..256 is given in Figure 6.7. Unfortunately, for these settings, the speedup shown here falls well short of the 3x speedup that theoretically could be obtained.

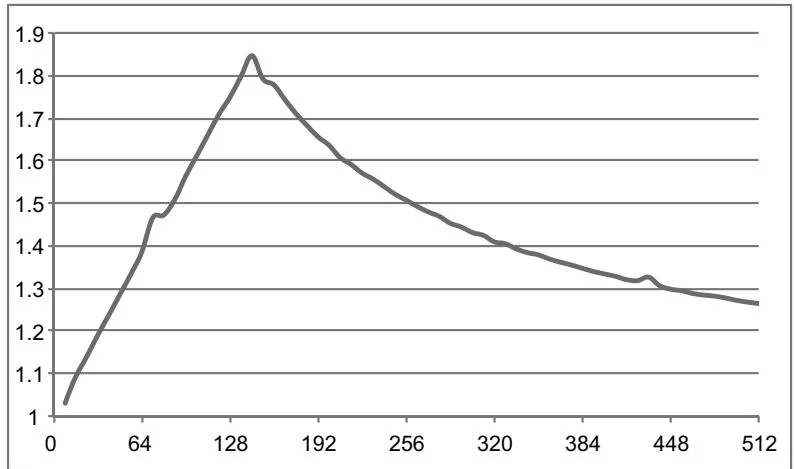

The benefit on a GeForce GTX 280, which contains only one copy engine, is more pronounced. Here, the results from varying cycles up to 512 are shown. The maximum speedup, shown in Figure 6.8, is much closer to the theoretical maximum of 2x.

Figure 6.8 Speedup due to memcpy/kernel concurrency (GeForce GTX 280).

As written, concurrencyMemcpyKernel.cu serves little more than an illustrative purpose, because AddValues() is just make-work. But you can plug your own kernel(s) into this application to help determine whether the additional complexity of using streams is justified by the performance improvement. Note that unless concurrent kernel execution is desired (see Section 6.7), the kernel invocation in Listing 6.5 could be replaced by successive kernel invocations in the same stream, and the application will still get the desired concurrency.

As a side note, the number of copy engines can be queried by calling CUDAGetDeviceProperties() and examining CUDADeviceProp::asyncEngineCount, or calling cuDeviceQueryAttribute() with CU_DEVICE_ATTRIBUTE_ASYNCENGINE_COUNT.

The copy engines accompanying SM 1.1 and some SM 1.2 hardware could copy linear memory only, but more recent copy engines offer full support for 2D memcpy, including 2D and 3D CUDA arrays.

6.5.3 BREAKING INTERENGINE CONCURRENCY

Using CUDA streams for concurrent memcpy and kernel execution introduces many more opportunities to "break concurrency." In the previous section, CPU/GPU concurrency could be broken by unintentionally doing something that caused CUDA to perform a full CPU/GPU synchronization. Here, CPU/GPU concurrency can be broken by unintentionally performing an unstreamed CUDA operation. Recall that the NULL stream performs a "join" on all GPU engines, so even an asynchronous memcpy operation will stall interengine concurrency if the NULL stream is specified.

Besides specifying the NULL stream explicitly, the main avenue for these unintentional "concurrency breaks" is calling functions that run in the NULL stream implicitly because they do not take a stream parameter. When streams were first introduced in CUDA 1.1, functions such as CUDAMemset() and cuMemcpyDtoD(), and the interfaces for libraries such as CUFFT and CUBLAS, did not have any way for applications to specify stream parameters. The Thrust library still does not include support. The CUDA Visual Profiler will call out concurrency breaks in its reporting.