6.1_CPU_GPU_Concurrency_Covering_Driver_Overhead

6.1 CPU/GPU Concurrency: Covering Driver Overhead

CPU/GPU concurrency refers to the CPU's ability to continue processing after having sent some request to the GPU. Arguably, the most important use of CPU/GPU concurrency is hiding the overhead of requesting work from the GPU.

6.1.1 KERNEL LAUNCHES

Kernel launches have always been asynchronous. A series of kernel launches, with no intervening CUDA operations in between, cause the CPU to submit the kernel launch to the GPU and return control to the caller before the GPU has finished processing.

We can measure the driver overhead by bracketing a series of NULL kernel launches with timing operations. Listing 6.1 shows nullKernelAsync.cu, a small program that measures the amount of time needed to perform a kernel launch.

Listing 6.1 nullKernelAsync.cu.

include<stdio.h>

#include"chTimer.h"

global_

void

NullKernel()

1

int main(int argc,char \*argv[]){ const int cIterations $=$ 1000000; printf("Launches...");fflush( stdout); chTimerTimestamp start,stop; chTimerGetTime(&start); for (int $\mathrm{i} = 0$ ;i $<$ cIterations; i++) { NullKernel<<1,1>>(); } CUDAThreadSynchronize(); chTimerGetTime(&stop); double microseconds $=$ 1e6\*chTimerElapsedTime(&start,&stop); double usPerLaunch $=$ microseconds / (float)cIterations; printf("%.2fus\n",usPerLaunch); return 0;

}The chTimerGetTime() calls, described in Appendix A, use the host operating system's high-resolution timing facilities, such as QueryPerformance-Counter() or gettimeofday(). The CUDAThreadSynchronize() call in line 23 is needed for accurate timing. Without it, the GPU would still be processing the last kernel invocations when the end top is recorded with the following function call.

chTimerGetTime( &stop );

If you run this program, you will see that invoking a kernel—even a kernel that does nothing—costs anywhere from 2.0 to 8.0 microseconds. Most of that time is spent in the driver. The CPU/GPU concurrency enabled by kernel launches only helps if the kernel runs for longer than it takes the driver to invoke it! To underscore the importance of CPU/GPU concurrency for small kernel launches, let's move the CUDAThreadSynchronize() call into the inner loop.1

chTimerGetTime( &start );

for ( int i = 0; i < cIterations; i++ ) { NullKernel<<1,1>>(); CUDAThreadSynchronize();

}

chTimerGetTime( &stop );

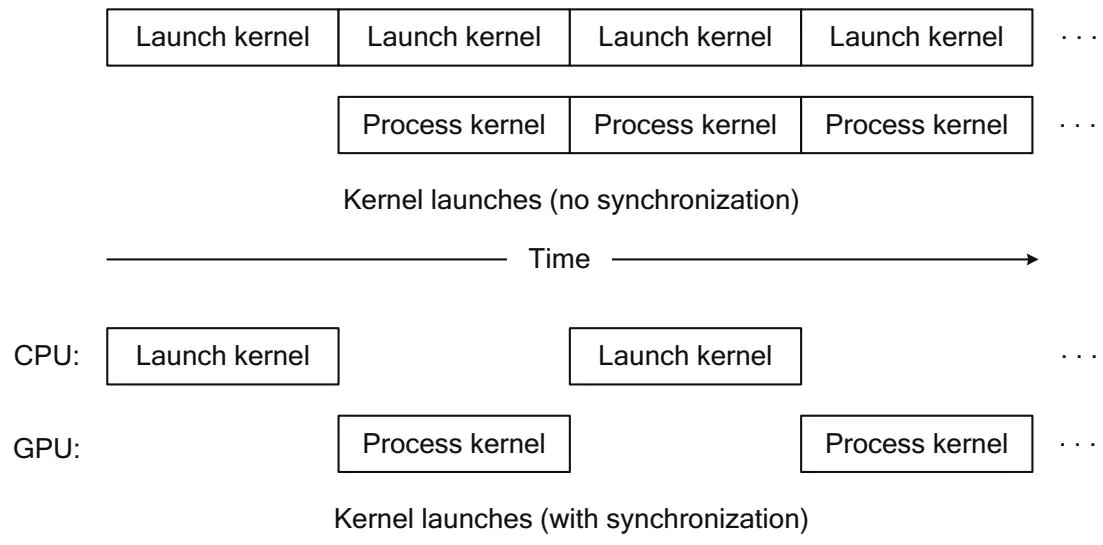

Figure 6.1 CPU/GPU concurrency.

The only difference here is that the CPU is waiting until the GPU has finished processing each NULL kernel launch before launching the next kernel, as shown in Figure 6.1. As an example, on an Amazon EC2 instance with ECC disabled, nullKernelNoSync reports a time of 3.4 ms per launch and nullKernelSync reports a time of 100 ms per launch. So besides giving up CPU/GPU concurrency, the synchronization itself is worth avoiding.

Even without synchronizations, if the kernel doesn't run for longer than the amount of time it took to launch the kernel (3.4 ms), the GPU may go idle before the CPU has submitted more work. To explore just how much work a kernel might need to do to make the launch worthwhile, let's switch to a kernel that busy-waits until a certain number of clock cycles (according to the clock ()) intrinsic) has completed.

__device__ int deviceTime;

__global_

void

WaitKernel( int cycles, bool bWrite ) { int start $=$ clock(); int stop; do{ stop $=$ clock(); } while (stop - start < cycles);if(bWrite&&threadIdx.x $\equiv = 0$ &&blockIdx.x $= = 0$ ){deviceTime $=$ stop - start;1}By conditionally writing the result to deviceTime, this kernel prevents the compiler from optimizing out the busy wait. The compiler does not know that we are just going to pass false as the second parameter. The code in our main () function then checks the launch time for various values of cycles, from 0 to 2500.

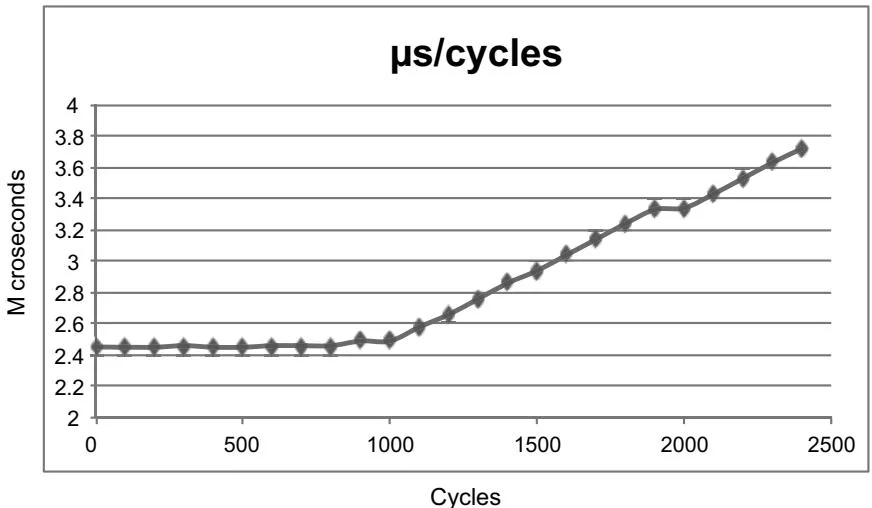

for ( int cycles = 0; cycles < 2500; cycles += 100 ) { printf( "Cycles: %d - ", cycles ); fflush( stdout ); chTimerGetTime( &start ); for ( int i = 0; i < cIterations; i++ ) { WaitKernel<<1,1>>>(cycles, false); } CUDAThreadSynchronize(); chTimerGetTime( &stop ); double microseconds = 1e6*chTimerElapsedTime( &start, &stop ); double usPerLaunch = microseconds / (float) cIterations; printf( "%.2f us\n", usPerLaunch ); }This program may be found in waitKernelAsync.cu. On our EC2 instance, the output is as in Figure 6.2. On this host platform, the breakeven mark where the kernel launch time crosses over that of a NULL kernel launch is at 4500 GPU clock cycles.

These performance characteristics can vary widely and depend on many factors, including the following.

Performance of the host CPU

Host operating system

Driver version

Driver model (TCC versus WDDM on Windows)

Whether ECC is enabled on the GPU3

Figure 6.2 Microseconds/cycles plot for waitKernelAsync.cu.

But the common underlying theme is that for most CUDA applications, developers should do their best to avoid breaking CPU/GPU concurrency. Only applications that are very compute-intensive and only perform large data transfers can afford to ignore this overhead. To take advantage of CPU/GPU concurrency when performing memory copies as well as kernel launches, developers must use asynchronous memcpy.