3.4_Solving_an_optimal_policy_from_the_BOE

3.4 Solving an optimal policy from the BOE

With the preparation in the last section, we are ready to solve the BOE to obtain the optimal state value and an optimal policy .

Solving : If is a solution of the BOE, then it satisfies

Clearly, is a fixed point because . Then, the contraction mapping theorem suggests the following results.

Theorem 3.3 (Existence, uniqueness, and algorithm). For the BOE , there always exists a unique solution , which can be solved iteratively by

The value of converges to exponentially fast as given any initial guess .

The proof of this theorem directly follows from the contraction mapping theorem since is a contraction mapping. This theorem is important because it answers some fundamental questions.

Existence of : The solution of the BOE always exists.

Uniqueness of : The solution is always unique.

Algorithm for solving : The value of can be solved by the iterative algorithm suggested by Theorem 3.3. This iterative algorithm has a specific name called value iteration. Its implementation will be introduced in detail in Chapter 4. We mainly focus on the fundamental properties of the BOE in the present chapter.

Solving : Once the value of has been obtained, we can easily obtain by solving

The value of will be given in Theorem 3.5. Substituting (3.6) into the BOE yields

Therefore, is the state value of , and the BOE is a special Bellman equation whose corresponding policy is .

At this point, although we can solve and , it is still unclear whether the solution is optimal. The following theorem reveals the optimality of the solution.

Theorem 3.4 (Optimality of and ). The solution is the optimal state value, and is an optimal policy. That is, for any policy , it holds that

where is the state value of , and is an elementwise comparison.

Now, it is clear why we must study the BOE: its solution corresponds to optimal state values and optimal policies. The proof of the above theorem is given in the following box.

Box 3.3: Proof of Theorem 3.4

For any policy , it holds that

Since

we have

Repeatedly applying the above inequality gives . It follows that

where the last equality is true because and is a nonnegative matrix with all its elements less than or equal to 1 (because ). Therefore, for any .

We next examine in (3.6) more closely. In particular, the following theorem shows that there always exists a deterministic greedy policy that is optimal.

Theorem 3.5 (Greedy optimal policy). For any , the deterministic greedy policy

is an optimal policy for solving the BOE. Here,

where

Box 3.4: Proof of Theorem 3.5

While the matrix-vector form of the optimal policy is , its elementwise form is

It is clear that is maximized if selects the action with the greatest .

The policy in (3.7) is called greedy because it seeks the actions with the greatest . Finally, we discuss two important properties of .

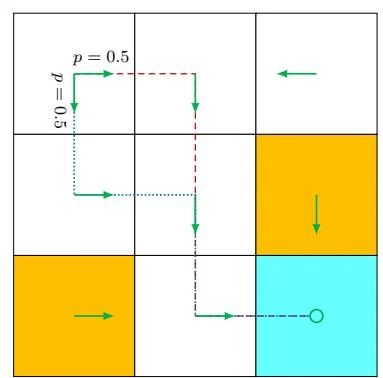

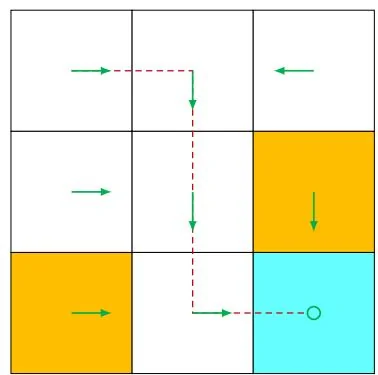

Uniqueness of optimal policies: Although the value of is unique, the optimal policy that corresponds to may not be unique. This can be easily verified by counterexamples. For example, the two policies shown in Figure 3.3 are both optimal.

Stochasticity of optimal policies: An optimal policy can be either stochastic or deterministic, as demonstrated in Figure 3.3. However, it is certain that there always exists a deterministic optimal policy according to Theorem 3.5.

Figure 3.3: Examples for demonstrating that optimal policies may not be unique. The two policies are different but are both optimal.