README

Appendix G - Coding Agents

Vibe Coding: A Starting Point

"Bibe coding" has become a powerful technique for rapid innovation and creative exploration. This practice involves using LLMs to generate initial drafts, outline complex logic, or build quick prototypes, significantly reducing initial friction. It is invaluable for overcoming the "blank page" problem, enabling developers to quickly transition from a vague concept to tangible, runnable code. Vibe coding is particularly effective when exploring unfamiliar APIs or testing novel architectural patterns, as it bypasses the immediate need for perfect implementation. The generated code often acts as a creative catalyst, providing a foundation for developers to critique, refactor, and expand upon. Its primary strength lies in its ability to accelerate the initial discovery and ideation phases of the software lifecycle. However, while vibe coding excels at brainstorming, developing robust, scalable, and maintainable software demands a more structured approach, shifting from pure generation to a collaborative partnership with specialized coding agents.

Agents as Team Members

While the initial wave focused on raw code generation—the "vibe code" perfect for ideation—the industry is now shifting towards a more integrated and powerful paradigm for production work. The most effective development teams are not merely delegating tasks to Agent; they are augmenting themselves with a suite of sophisticated coding agents. These agents act as tireless, specialized team members, amplifying human creativity and dramatically increasing a team's scalability and velocity.

This evolution is reflected in statements from industry leaders. In early 2025, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai noted that at Google, "over of new code is now assisted or generated by our Gemini models, fundamentally changing our development velocity. Microsoft made a similar claim. This industry-wide shift signals that the true frontier is not replacing developers, but empowering them. The goal is an augmented relationship where humans guide the architectural vision and creative problem-solving, while agents handle specialized, scalable tasks like testing, documentation, and review.

This chapter presents a framework for organizing a human-agent team based on the core philosophy that human developers act as creative leads and architects, while AI agents function as force multipliers. This framework rests upon three foundational principles:

Human-Led Orchestration: The developer is the team lead and project architect. They are always in the loop, orchestrating the workflow, setting the high-level goals, and making the final decisions. The agents are powerful, but they are supportive collaborators. The developer directs which agent to engage, provides the necessary

context, and, most importantly, exercises the final judgment on any Agent-generated output, ensuring it aligns with the project's quality standards and long-term vision.

The Primacy of Context: An agent's performance is entirely dependent on the quality and completeness of its context. A powerful LLM with poor context is useless. Therefore, our framework prioritizes a meticulous, human-led approach to context curation. Automated, black-box context retrieval is avoided. The developer is responsible for assembling the perfect "briefing" for their Agent team member. This includes:

The Complete Codebase: Providing all relevant source code so the agent understands the existing patterns and logic.

External Knowledge: Supplying specific documentation, API definitions, or design documents.

The Human Brief: Articulating clear goals, requirements, pull request descriptions, and style guides.

Direct Model Access: To achieve state-of-the-art results, the agents must be powered by direct access to frontier models (e.g., Gemini 2.5 PRO, Claude Opus 4, OpenAI, DeepSeek, etc). Using less powerful models or routing requests through intermediary platforms that obscure or truncate context will degrade performance. The framework is built on creating the purest possible dialogue between the human lead and the raw capabilities of the underlying model, ensuring each agent operates at its peak potential.

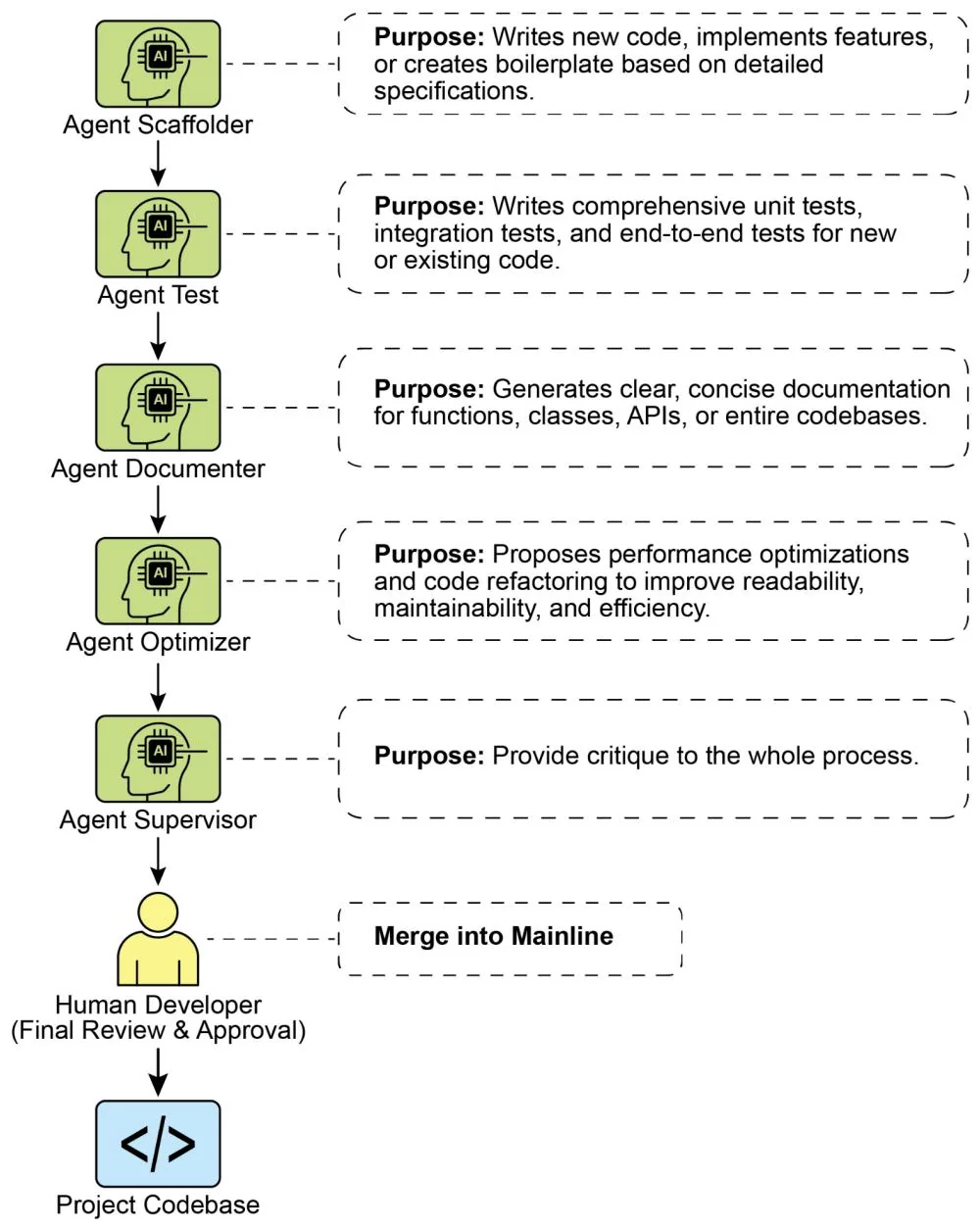

The framework is structured as a team of specialized agents, each designed for a core function in the development lifecycle. The human developer acts as the central orchestrator, delegating tasks and integrating the results.

Core Components

To effectively leverage a frontier Large Language Model, this framework assigns distinct development roles to a team of specialized agents. These agents are not separate applications but are conceptual personas invoked within the LLM through carefully crafted, role-specific prompts and contexts. This approach ensures that the model's vast capabilities are precisely focused on the task at hand, from writing initial code to performing a nuanced, critical review.

The Orchestrator: The Human Developer: In this collaborative framework, the human developer acts as the Orchestrator, serving as the central intelligence and ultimate authority over the AI agents.

○ Role: Team Lead, Architect, and final decision-maker. The orchestrator defines tasks, prepares the context, and validates all work done by the agents.

○ Interface: The developer's own terminal, editor, and the native web UI of the chosen Agents.

The Context Staging Area: As the foundation for any successful agent interaction, the Context Staging Area is where the human developer meticulously prepares a complete and task-specific briefing.

○ Role: A dedicated workspace for each task, ensuring agents receive a complete and accurate briefing.

○ Implementation: A temporary directory (task-context/) containing markdown files for goals, code files, and relevant docs

The Specialist Agents: By using targeted prompts, we can build a team of specialist agents, each tailored for a specific development task.

The Scaffolder Agent: The Implementer

Purpose: Writes new code, implements features, or creates boilerplate based on detailed specifications.

■ Invocation Prompt: "You are a senior software engineer. Based on the requirements in 01_BRIEF.md and the existing patterns in 02_CODE/, implement the feature."

The Test Engineer Agent: The Quality Guard

Purpose: Writes comprehensive unit tests, integration tests, and end-to-end tests for new or existing code.

■ Invocation Prompt: "You are a quality assurance engineer. For the code provided in 02_CODE/, write a full suite of unit tests using [Testing Framework, e.g., pytest]. Cover all edge cases and adhere to the project's testing philosophy."

The Documenter Agent: The Scribe

Purpose: Generates clear, concise documentation for functions, classes, APIs, or entire codebases.

■ Invocation Prompt: "You are a technical writer. Generate markdown documentation for the API endpoints defined in the provided code. Include request/response examples and explain each parameter."

The Optimizer Agent: The Refactoring Partner

Purpose: Proposes performance optimizations and code refactoring to improve readability, maintainability, and efficiency.

■ Invocation Prompt: "Analyze the provided code for performance bottlenecks on areas that could be refactored for clarity. Propose specific changes with explanations for why they are an improvement."

The Process Agent: The Code Supervisor

Critique: The agent performs an initial pass, identifying potential bugs, style violations, and logical flaws, much like a static analysis tool.

Reflection: The agent then analyzes its own critique. It synthesizes the findings, prioritizes the most critical issues, dismisses pedantic or low-impact suggestions, and provides a high-level, actionable summary for the human developer.

■ Invocation Prompt: "You are a principal engineer conducting a code review. First, perform a detailed critique of the changes. Second, reflect on your critique to provide a concise, prioritized summary of the most important feedback."

Ultimately, this human-led model creates a powerful synergy between the developer's strategic direction and the agents' tactical execution. As a result, developers can transcend routine tasks, focusing their expertise on the creative and architectural challenges that deliver the most value.

Practical Implementation

Setup Checklist

To effectively implement the human-agent team framework, the following setup is recommended, focusing on maintaining control while improving efficiency.

Provision Access to Frontier Models Secure API keys for at least two leading large language models, such as Gemini 2.5 Pro and Claude 4 Opus. This dual-provider approach allows for comparative analysis and hedges against single-platform limitations or downtime. These credentials should be managed securely as you would any other production secret.

Implement a Local Context Orchestrator Instead of ad-hoc scripts, use a lightweight CLI tool or a local agent runner to manage context. These tools should allow you to define a simple configuration file (e.g., context.toml) in your project root that specifies which files, directories, or even URLs to compile into a single payload for the LLM prompt. This ensures you retain full, transparent control over what the model sees on every request.

Establish a Version-Controlled Prompt Library Create a dedicated /prompts directory within your project's Git repository. In it, store the invocation prompts for each specialist agent (e.g., reviewer.md, documenter.md, tester.md) as markdown files. Treating your prompts as code allows the entire team to collaborate on, refine, and version the instructions given to your AI agents over time.

Integrate Agent Workflows with Git Hooks Automate your review rhythm by using local Git hooks. For instance, a pre-commit hook can be configured to automatically trigger the Reviewer Agent on your staged changes. The agent's critique-and-reflection summary can be presented directly in your terminal, providing immediate feedback before you finalize the commit and baking the quality assurance step directly into your development process.

Fig. 1: Coding Specialist Examples

Principles for Leading the Augmented Team

Successfully leading this framework requires evolving from a sole contributor into the lead of a human-AI team, guided by the following principles:

Maintain Architectural Ownership Your role is to set the strategic direction and own the high-level architecture. You define the "what" and the "why," using the agent team to accelerate the "how." You are the final arbiter of design, ensuring every component aligns with the project's long-term vision and quality standards.

Master the Art of the Brief The quality of an agent's output is a direct reflection of the quality of its input. Master the art of the brief by providing clear, unambiguous, and comprehensive context for every task. Think of your prompt not as a simple command, but as a complete briefing package for a new, highly capable team member.

Act as the Ultimate Quality Gate An agent's output is always a proposal, never a command. Treat the Reviewer Agent's feedback as a powerful signal, but you are the ultimate quality gate. Apply your domain expertise and project-specific knowledge to validate, challenge, and approve all changes, acting as the final guardian of the codebase's integrity.

Engage in Iterative Dialogue The best results emerge from conversation, not monologue. If an agent's initial output is imperfect, don't discard it—refine it. Provide corrective feedback, add clarifying context, and prompt for another attempt. This iterative dialogue is crucial, especially with the Reviewer Agent, whose "Reflection" output is designed to be the start of a collaborative discussion, not just a final report.

Conclusion

The future of code development has arrived, and it is augmented. The era of the lone coder has given way to a new paradigm where developers lead teams of specialized AI agents. This model doesn't diminish the human role; it elevates it by automating routine tasks, scaling individual impact, and achieving a development velocity previously unimaginable.

By offloading tactical execution to Agents, developers can now dedicate their cognitive energy to what truly matters: strategic innovation, resilient architectural design, and the creative problem-solving required to build products that delight users. The fundamental relationship has been redefined; it is no longer a contest of human versus machine, but a partnership between human ingenuity and AI, working as a single, seamlessly integrated team.

References

AI is responsible for generating more than of the code at Google https://www.reddit.com/r/singularity/comments/1k7rxoO/ai_is_now-writing_well_over_30_of_the_code.at/

AI is responsible for generating more than of the code at Microsoft https://www.businesstoday.in/tech- today/news/story/30- of- microsofts- code- is- now- ai -generated- says- ceo- satya-nadella- 474167- 2025- 04- 30

Conclusion

Throughout this book we have journeyed from the foundational concepts of agentic AI to the practical implementation of sophisticated, autonomous systems. We began with the premise that building intelligent agents is akin to creating a complex work of art on a technical canvas—a process that requires not just a powerful cognitive engine like a large language model, but also a robust set of architectural blueprints. These blueprints, or agentic patterns, provide the structure and reliability needed to transform simple, reactive models into proactive, goal-oriented entities capable of complex reasoning and action.

This concluding chapter will synthesize the core principles we have explored. We will first review the key agentic patterns, grouping them into a cohesive framework that underscores their collective importance. Next, we will examine how these individual patterns can be composed into more complex systems, creating a powerful synergy. Finally, we will look ahead to the future of agent development, exploring the emerging trends and challenges that will shape the next generation of intelligent systems.

Review of key agentic principles

The 21 patterns detailed in this guide represent a comprehensive toolkit for agent development. While each pattern addresses a specific design challenge, they can be understood collectively by grouping them into foundational categories that mirror the core competencies of an intelligent agent.

Core Execution and Task Decomposition: At the most fundamental level, agents must be able to execute tasks. The patterns of Prompt Chaining, Routing, Parallelization, and Planning form the bedrock of an agent's ability to act. Prompt Chaining provides a simple yet powerful method for breaking down a problem into a linear sequence of discrete steps, ensuring that the output of one operation logically informs the next. When workflows require more dynamic behavior, Routing introduces conditional logic, allowing an agent to select the most appropriate path or tool based on the context of the input. Parallelization optimizes efficiency by enabling the concurrent execution of independent sub-tasks, while the Planning pattern elevates the agent from a mere executor to a strategist, capable of formulating a multi-step plan to achieve a high-level objective.

Interaction with the External Environment: An agent's utility is significantly enhanced by its ability to interact with the world beyond its immediate internal state. The Tool Use (Function Calling) pattern is paramount here, providing the mechanism for agents to leverage external APIs, databases, and other software systems. This grounds the agent's operations in real-world data and capabilities. To effectively use these tools, agents must often access specific, relevant information from vast repositories. The Knowledge Retrieval pattern, particularly Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), addresses this by enabling agents to query knowledge bases and incorporate that information into their responses, making them more accurate and contextually aware.

State, Learning, and Self-Improvement: For an agent to perform more than just single-turn tasks, it must possess the ability to maintain context and improve over time. The Memory Management pattern is crucial for endowing agents with both short-term conversational context and long-term knowledge retention. Beyond simple memory, truly intelligent agents exhibit the capacity for self-improvement. The Reflection and Self-Correction patterns enable an agent to critique its own output, identify errors or shortcomings, and iteratively refine its work, leading to a higher quality final result. The Learning and Adaptation pattern takes this a step further, allowing an agent's behavior to evolve based on feedback and experience, making it more effective over time.

Collaboration and Communication: Many complex problems are best solved through collaboration. The Multi-Agent Collaboration pattern allows for the creation of systems where multiple specialized agents, each with a distinct role and set of capabilities, work together to achieve a common goal. This division of labor enables the system to tackle multifaceted problems that would be intractable for a single agent. The effectiveness of such systems hinges on clear and efficient communication, a challenge addressed by the Inter-Agent Communication (A2A) and Model Context Protocol (MCP) patterns, which aim to standardize how agents and tools exchange information.

These principles, when applied through their respective patterns, provide a robust framework for building intelligent systems. They guide the developer in creating agents that are not only capable of performing complex tasks but are also structured, reliable, and adaptable.

Combining Patterns for Complex Systems

The true power of agentic design emerges not from the application of a single pattern in isolation, but from the artful composition of multiple patterns to create

sophisticated, multi-layered systems. The agentic canvas is rarely populated by a single, simple workflow; instead, it becomes a tapestry of interconnected patterns that work in concert to achieve a complex objective.

Consider the development of an autonomous AI research assistant, a task that requires a combination of planning, information retrieval, analysis, and synthesis. Such a system would be a prime example of pattern composition:

Initial Planning: A user query, such as "Analyze the impact of quantum computing on the cybersecurity landscape," would first be received by a Planner agent. This agent would leverage the Planning pattern to decompose the high-level request into a structured, multi-step research plan. This plan might include steps like "Identify foundational concepts of quantum computing," "Research common cryptographic algorithms," "Find expert analyses on quantum threats to cryptography," and "Synthesize findings into a structured report."

Information Gathering with Tool Use: To execute this plan, the agent would rely heavily on the Tool Use pattern. Each step of the plan would trigger a call to a Google Search or vertex.ai_search tool. For more structured data, it might use tools to query academic databases like ArXiv or financial data APIs.

Collaborative Analysis and Writing: A single agent might handle this, but a more robust architecture would employ Multi-Agent Collaboration. A "Researcher" agent could be responsible for executing the search plan and gathering raw information. Its output—a collection of summaries and source links—would then be passed to a "Writer" agent. This specialist agent, using the initial plan as its outline, would synthesize the collected information into a coherent draft.

Iterative Reflection and Refinement: A first draft is rarely perfect. The Reflection pattern could be implemented by introducing a third "Critic" agent. This agent's sole purpose would be to review the Writer's draft, checking for logical inconsistencies, factual inaccuracies, or areas lacking clarity. Its critique would be fed back to the Writer agent, which would then leverage the Self-Correction pattern to refine its output, incorporating the feedback to produce a higher-quality final report.

State Management: Throughout this entire process, a Memory Management system would be essential. It would maintain the state of the research plan, store the information gathered by the Researcher, hold the drafts created by the Writer, and track the feedback from the Critic, ensuring that context is preserved across the entire multi-step, multi-agent workflow.

In this example, at least five distinct agentic patterns are woven together. The Planning pattern provides the high-level structure, Tool Use grounds the operation in real-world data, Multi-Agent Collaboration enables specialization and division of labor, Reflection ensures quality, and Memory Management maintains coherence. This composition transforms a set of individual capabilities into a powerful, autonomous system capable of tackling a task that would be far too complex for a single prompt or a simple chain.

Looking to the Future

The composition of agentic patterns into complex systems, as illustrated by our AI research assistant, is not the end of the story but rather the beginning of a new chapter in software development. As we look ahead, several emerging trends and challenges will define the next generation of intelligent systems, pushing the boundaries of what is possible and demanding even greater sophistication from their creators.

The journey toward more advanced agentic AI will be marked by a drive for greater autonomy and reasoning. The patterns we have discussed provide the scaffolding for goal-oriented behavior, but the future will require agents that can navigate ambiguity, perform abstract and causal reasoning, and even exhibit a degree of common sense. This will likely involve tighter integration with novel model architectures and neuro-symbolic approaches that blend the pattern-matching strengths of LLMs with the logical rigor of classical AI. We will see a shift from human-in-the-loop systems, where the agent is a co-pilot, to human-on-the-loop systems, where agents are trusted to execute complex, long-running tasks with minimal oversight, reporting back only when the objective is complete or a critical exception occurs.

This evolution will be accompanied by the rise of agentic ecosystems and standardization. The Multi-Agent Collaboration pattern highlights the power of specialized agents, and the future will see the emergence of open marketplaces and platforms where developers can deploy, discover, and orchestrate fleets of agents-as-a-service. For this to succeed, the principles behind the Model Context Protocol (MCP) and Inter-Agent Communication (A2A) will become paramount, leading to industry-wide standards for how agents, tools, and models exchange not just data, but also context, goals, and capabilities.

A prime example of this growing ecosystem is the "Awesome Agents" GitHub repository, a valuable resource that serves as a curated list of open-source AI agents, frameworks, and tools. It showcases the rapid innovation in the field by organizing cutting-edge projects for applications ranging from software development to autonomous research and conversational AI.

However, this path is not without its formidable challenges. The core issues of safety, alignment, and robustness will become even more critical as agents become more autonomous and interconnected. How do we ensure an agent's learning and adaptation do not cause it to drift from its original purpose? How do we build systems that are resilient to adversarial attacks and unpredictable real-world scenarios? Answering these questions will require a new set of "safety patterns" and a rigorous engineering discipline focused on testing, validation, and ethical alignment.

Final Thoughts

Throughout this guide, we have framed the construction of intelligent agents as an art form practiced on a technical canvas. These Agentic Design patterns are your palette and your brushstrokes—the foundational elements that allow you to move beyond simple prompts and create dynamic, responsive, and goal-oriented entities. They provide the architectural discipline needed to transform the raw cognitive power of a large language model into a reliable and purposeful system.

The true craft lies not in mastering a single pattern but in understanding their interplay—in seeing the canvas as a whole and composing a system where planning, tool use, reflection, and collaboration work in harmony. The principles of agentic design are the grammar of a new language of creation, one that allows us to instruct machines not just on what to do, but on how to be.

The field of agentic AI is one of the most exciting and rapidly evolving domains in technology. The concepts and patterns detailed here are not a final, static dogma but a starting point—a solid foundation upon which to build, experiment, and innovate. The future is not one where we are simply users of AI, but one where we are the architects of intelligent systems that will help us solve the world's most complex problems. The canvas is before you, the patterns are in your hands. Now, it is time to build.

Glossary

Fundamental Concepts

Prompt: A prompt is the input, typically in the form of a question, instruction, or statement, that a user provides to an AI model to elicit a response. The quality and structure of the prompt heavily influence the model's output, making prompt engineering a key skill for effectively using AI.

Context Window: The context window is the maximum number of tokens an AI model can process at once, including both the input and its generated output. This fixed size is a critical limitation, as information outside the window is ignored, while larger windows enable more complex conversations and document analysis.

In-Context Learning: In-context learning is an AI's ability to learn a new task from examples provided directly in the prompt, without requiring any retraining. This powerful feature allows a single, general-purpose model to be adapted to countless specific tasks on the fly.

Zero-Shot, One-Shot, & Few-Shot Prompting: These are prompting techniques where a model is given zero, one, or a few examples of a task to guide its response. Providing more examples generally helps the model better understand the user's intent and improves its accuracy for the specific task.

Multimodality: Multimodality is an AI's ability to understand and process information across multiple data types like text, images, and audio. This allows for more versatile and human-like interactions, such as describing an image or answering a spoken question.

Grounding: Grounding is the process of connecting a model's outputs to verifiable, real-world information sources to ensure factual accuracy and reduce hallucinations. This is often achieved with techniques like RAG to make AI systems more trustworthy.

Core AI Model Architectures Transformers: The Transformer is the foundational neural network architecture for most modern LLMs. Its key innovation is the self-attention mechanism, which efficiently processes long sequences of text and captures complex relationships between words.

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN): The Recurrent Neural Network is a foundational architecture that preceded the Transformer. RNNs process information sequentially, using loops to maintain a "memory" of previous inputs, which made them suitable for tasks like text and speech processing.

Mixture of Experts (MoE): Mixture of Experts is an efficient model architecture where a "router" network dynamically selects a small subset of "expert" networks to handle any given input. This allows models to have a massive number of parameters while keeping computational costs manageable.

Diffusion Models: Diffusion models are generative models that excel at creating high-quality images. They work by adding random noise to data and then training a model to meticulously reverse the process, allowing them to generate novel data from a random starting point.

Mamba: Mamba is a recent AI architecture using a Selective State Space Model (SSM) to process sequences with high efficiency, especially for very long contexts. Its selective mechanism allows it to focus on relevant information while filtering out noise, making it a potential alternative to the Transformer.

The LLM Development Lifecycle

The development of a powerful language model follows a distinct sequence. It begins with Pre-training, where a massive base model is built by training it on a vast dataset of general internet text to learn language, reasoning, and world knowledge. Next is Fine-tuning, a specialization phase where the general model is further trained on smaller, task-specific datasets to adapt its capabilities for a particular purpose. The final stage is Alignment, where the specialized model's behavior is adjusted to ensure its outputs are helpful, harmless, and aligned with human values.

Pre-training Techniques: Pre-training is the initial phase where a model learns general knowledge from vast amounts of data. The top techniques for this involve different objectives for the model to learn from. The most common is Causal Language Modeling (CLM), where the model predicts the next word in a sentence. Another is Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where the model fills in intentionally hidden words in a text. Other important methods include Denoising Objectives, where the model learns to restore a corrupted input to its original state, Contrastive Learning, where it learns to distinguish between similar and dissimilar pieces of data, and Next Sentence Prediction

(NSP), where it determines if two sentences logically follow each other.

Fine-tuning Techniques: Fine-tuning is the process of adapting a general pre-trained model to a specific task using a smaller, specialized dataset. The most common approach is Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), where the model is trained on labeled examples of correct input-output pairs. A popular variant is Instruction Tuning, which focuses on training the model to better follow user commands. To make this process more efficient, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods are used, with top techniques including LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), which only updates a small number of parameters, and its memory-optimized version, QLoRA. Another technique,

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), enhances the model by connecting it to an external knowledge source during the fine-tuning or inference stage.

Alignment & Safety Techniques:

Alignment is the process of ensuring an AI model's behavior aligns with human values and expectations, making it helpful and harmless. The most prominent technique is Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), where a "reward model" trained on human preferences guides the AI's learning process, often using an algorithm like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) for stability. Simpler alternatives have emerged, such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), which bypasses the need for a separate reward model, and Kahneman-Tversky Optimization (KTO), which simplifies data collection further. To ensure safe

deployment, Guardrails are implemented as a final safety layer to filter outputs and block harmful actions in real-time.

Enhancing AI Agent Capabilities

AI agents are systems that can perceive their environment and take autonomous actions to achieve goals. Their effectiveness is enhanced by robust reasoning frameworks.

Chain of Thought (CoT): This prompting technique encourages a model to explain its reasoning step-by-step before giving a final answer. This process of "thinking out loud" often leads to more accurate results on complex reasoning tasks.

Tree of Thoughts (ToT): Tree of Thoughts is an advanced reasoning framework where an agent explores multiple reasoning paths simultaneously, like branches on a tree. It allows the agent to self-evaluate different lines of thought and choose the most promising one to pursue, making it more effective at complex problem-solving.

ReAct (Reason and Act): ReAct is an agent framework that combines reasoning and acting in a loop. The agent first "thinks" about what to do, then takes an "action" using a tool, and uses the resulting observation to inform its next thought, making it highly effective at solving complex tasks.

Planning: This is an agent's ability to break down a high-level goal into a sequence of smaller, manageable sub-tasks. The agent then creates a plan to execute these steps in order, allowing it to handle complex, multi-step assignments.

Deep Research: Deep research refers to an agent's capability to autonomously explore a topic in-depth by iteratively searching for information, synthesizing findings, and identifying new questions. This allows the agent to build a comprehensive understanding of a subject far beyond a single search query.

Critique Model: A critique model is a specialized AI model trained to review, evaluate, and provide feedback on the output of another AI model. It acts as an automated critic, helping to identify errors, improve reasoning, and ensure the final output meets a desired quality standard.

Index of Terms

This index of terms was generated using Gemini Pro 2.5. The prompt and reasoning steps are included at the end to demonstrate the time-saving benefits and for educational purposes.

A

A/B Testing - Chapter 3: Parallelization

Action Selection - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Adaptation - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Adaptive Task Allocation - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Adaptive Tool Use & Selection - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Agent - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Agent-Computer Interfaces (ACIs) - Appendix B

Agent-Driven Economy - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Agent as a Tool - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Agent Cards - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Agent Development Kit (ADK) - Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A), Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring, Appendix C

Agent Discovery - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Agent Trajectories - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Agentic Design Patterns - Introduction

Agentic RAG - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Agentic Systems - Introduction

Al Co-scientist - Chapter 21: Exploration and DiscoveryAlignment - Glossary

AlphaEvolve - Chapter 9: Learning and AdaptationAnalogies - Appendix A

Anomaly Detection - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Anthropic's Claude 4 Series - Appendix B

Anthropic's Computer Use - Appendix B

API Interaction - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Artifacts - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Asynchronous Polling - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Audit Logs - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Automated Metrics - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE) - Appendix A

Autonomy - Introduction

A2A (Agent-to-Agent) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

B

Behavioral Constraints - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Browser Use - Appendix B

C

Callbacks - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Causal Language Modeling (CLM) - Glossary

Chain of Debates (CoD) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A

Chatbots - Chapter 8: Memory Management

ChatMessageHistory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Checkpoint and Rollback - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Chunking - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Clarity and Specificity - Appendix A

Client Agent - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Code Generation - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Code Prompting - Appendix A

CoD (Chain of Debates) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

CoT (Chain of Thought) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A

Collaboration - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent CollaborationCompliance - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Conciseness - Appendix A

Content Generation - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Context Engineering - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Context Window - Glossary

Contextual Pruning & Summarization - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Contextual Prompting - Appendix A

Contractor Model - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

ConversationBufferMemory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Conversational Agents - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Cost-Sensitive Exploration - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

CrewAl - Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 6: Planning, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns, Appendix C

Critique Agent - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Critique Model - Glossary

Customer Support - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

D

Data Extraction - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Data Labeling - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Database Integration - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

DatabaseSessionService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Debate and Consensus - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Decision Augmentation - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Decomposition - Appendix A

Deep Research - Chapter 6: Planning, Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Glossary

Delimiters - Appendix A

Denoising Objectives - Glossary

Dependencies - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Diffusion Models - GlossaryDirect Preference Optimization (DPO) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Discoverability - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)Drift Detection - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Dynamic Model Switching - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Dynamic Re-prioritization - Chapter 20: Prioritization

E

Embeddings - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Embodiment - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Energy-Efficient Deployment - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Episodic Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Error Detection - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Error Handling - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Escalation Policies - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Evaluation - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Exception Handling - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Expert Teams - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Exploration and Discovery - Chapter 21: Exploration and Discovery

External Moderation APIs - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

F

Factored Cognition - Appendix A

FastMCP - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Fault Tolerance - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Few-Shot Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Few-Shot Prompting - Appendix A

Fine-tuning - Glossary

Formalized Contract - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Function Calling - Chapter 5: Tool Use, Appendix A

G

Gemini Live - Appendix B

Gems - Appendix A

Generative Media Orchestration - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Goal Setting - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring

GoD (Graph of Debates) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Google Agent Development Kit (ADK) - Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A), Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring, Appendix C

Google Co-Scientist - Chapter 21: Exploration and Discovery

Google DeepResearch - Chapter 6: PlanningGoogle Project Mariner - Appendix B

Graceful Degradation - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Graph of Debates (GoD) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Grounding - Glossary

Guardrails - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

H

Haystack - Appendix C

Hierarchical Decomposition - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Hierarchical Structures - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

HITL (Human-in-the-Loop) - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human-on-the-loop - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human Oversight - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

1

In-Context Learning - Glossary

InMemoryMemoryService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

InMemorySessionService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Input Validation/Sanitization - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Instructions Over Constraints - Appendix A

Inter-Agent Communication (A2A) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Intervention and Correction - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

IoT Device Control - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Iterative Prompting / Refinement - Appendix A

J

Jailbreaking - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

K

Kahneman-Tversky Optimization (KTO) - Glossary

Knowledge Retrieval (RAG) - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

L

LangChain - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 20: Prioritization, Appendix C

LangGraph - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Appendix C

Latency Monitoring - Chapter 19: Evaluation and MonitoringLearned Resource Allocation Policies - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Learning and Adaptation - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

LLM-as-a-Judge - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

LlamalIndex - Appendix C

LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) - Glossary

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) - Glossary

M

Mamba - Glossary

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) - Glossary

MASS (Multi-Agent System Search) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

MCP (Model Context Protocol) - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)Memory Management - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Memory-Based Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

MetaGPT - Appendix CMicrosoft AutoGen - Appendix C

Mixture of Experts (MoE) - Glossary

Model Context Protocol (MCP) - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Modularity - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety PatternsMonitoring - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Multi-Agent Collaboration - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Multi-Agent System Search (MASS) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Multimodality - Glossary

Multimodal Prompting - Appendix A

N

Negative Examples - Appendix A

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) - Glossary

0

Observability - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

One-Shot Prompting - Appendix A

Online Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

OpenAI Deep Research API - Chapter 6: Planning

OpenEvolve - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

OpenRouter - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Output Filtering/Post-processing - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

P

PAL (Program-Aided Language Models) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Parallelization - Chapter 3: Parallelization

Parallelization & Distributed Computing Awareness - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) - Glossary

PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) - Glossary

Performance Tracking - Chapter 19: Evaluation and MonitoringPersona Pattern - Appendix A

Personalization - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Planning - Chapter 6: Planning, Glossary

Prioritization - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Principle of Least Privilege - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Proactive Resource Prediction - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Procedural Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Program-Aided Language Models (PAL) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Project Astra - Appendix B

Prompt - Glossary

Prompt Chaining - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Prompt Engineering - Appendix A

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Push Notifications - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Q

QLoRA - Glossary

Quality-Focused Iterative Execution - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

R

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) - Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG), Appendix A

ReAct (Reason and Act) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A, Glossary

Reasoning - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Reasoning-Based Information Extraction - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Recovery - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) - Glossary

Reflection - Chapter 4: Reflection

Reinforcement Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) - Glossary

Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Remote Agent - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Request/Response (Polling) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Resource-Aware Optimization - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware OptimizationRetrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) - Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG), Appendix A

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) - Glossary

RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) - Glossary

Role Prompting - Appendix ARouter Agent - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Routing - Chapter 2: Routing

s

Safety - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Scaling Inference Law - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Scheduling - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Self-Consistency - Appendix A

Self-Correction - Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Self-Improving Coding Agent (SICA) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Self-Refinement - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Semantic Kernel - Appendix C

Semantic Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Semantic Similarity - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Separation of Concerns - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Sequential Handoffs - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Server-Sent Events (SSE) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Session - Chapter 8: Memory Management

SICA (Self-Improving Coding Agent) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

SMART Goals - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring

State - Chapter 8: Memory Management

State Rollback - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and RecoveryStep-Back Prompting - Appendix A

Streaming Updates - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Structured Logging - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Structured Output - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Appendix A

SuperAGI - Appendix C

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) - Glossary

Supervised Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and AdaptationSystem Prompting - Appendix A

T

Task Evaluation - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Text Similarity - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)Token Usage - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Tool Use - Chapter 5: Tool Use, Appendix A

Tool Use Restrictions - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

ToT (Tree of Thoughts) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A, Glossary

Transformers - Glossary

Tree of Thoughts (ToT) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A, Glossary

U

Unsupervised Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

User Persona - Appendix A

V

Validation - Chapter 3: Parallelization

Vector Search - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

VertexAiRagMemoryService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

VertexAiSessionService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Vibe Coding - Appendix B

Visual Perception - Appendix B

W

Webhooks - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Z

Zero-Shot Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Zero-Shot Prompting - Appendix A

Prompt

Below is the prompt that was utilized to create this index of terms.

do you read

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1rsaK53T3Lg5KoGwvf8ukOUvbELRtH-V0LnOIFDxBryE/ edit?tab t.0 and all the related documents in the first page Please extract all the titles for each chapter. and print them. Then process the content of all the individual chapters, and create a detailed index used for publishing, a list of words or phrases ('headings') and associated pointers ('locators') to where useful material relating to that heading can be found in a document or collection of documents. I don't want a sample index. I want the full index, with 100 index terms

Gemini 2.5: Reasoning Steps

Beginning Index Creation

I've initiated the process by reading the Google Doc provided. Currently, I'm focusing on understanding the user's request: extracting chapter titles to build a detailed index. I'm carefully reviewing the document, looking for clear structural elements that would indicate chapter breaks. I'm hoping to identify consistent formatting or keywords that will guide the indexing process.

Defining Index Extraction Process

I'm now fully immersed in the task. I've broken down the user's request into actionable steps. My initial focus is using Workspaces to access the main Google Doc. Following this, I'll parse the document to locate and retrieve related documents, which will also be accessed using the same tool. Finally, I will extract all chapter titles from all the documents, and create a comprehensive index. I've planned the detailed process.

Refining the Extraction Strategy

The user's instructions are clear: read a Google Doc, its related documents, and build a detailed index of chapter titles. I've devised a multi-step plan. First, Workspaces will access the main Google Doc. Then, I'll parse it to find and read related documents, also using Workspaces. I'm now focusing on extracting titles and forming the detailed index with the required terms. I'm prioritizing accuracy to meet the user's specific demands for a comprehensive index.

1. Establish user intent:

I've determined the user wants a chapter title list and comprehensive index from the Google Doc and related documents. Now I need to figure out the most effective method for this extraction and indexing process. I'm exploring potential API functionalities to streamline this task, and will need to assess the best strategy for handling different document structures.

3. Considering Tool Use

I've extracted the chapter URLs from the main document using a regular expression. Now, I'm ready to utilize Workspaces to retrieve the actual content of each chapter. Once I have the text for each chapter, I'll proceed with indexing.

Accessing chapter content:

I've successfully identified the URLs for each chapter from the main document, which I can now use with Workspaces. My next step is to retrieve the content from these URLs, which will then allow me to generate the index. I'm focusing on efficiency, aiming to process this information quickly.

Fetching Chapter Content

I've successfully identified the chapter URLs from the main document and am ready to utilize Workspaces. My plan involves extracting these URLs, batching the calls for efficiency, and then processing the retrieved content to create the desired index. This ensures all relevant information is captured, paving the way for a comprehensive and accurate result.

Initiating URL Retrieval

I've now successfully extracted the chapter URLs from the main document. Currently, I'm setting up calls to the Workspaces tool, preparing to fetch the content of each chapter. The goal is to obtain the necessary text for indexing. This information will then facilitate the creation of the index with at least 100 terms as requested.

Initiating Chapter Extraction

I've successfully identified and extracted the chapter URLs from the main document, which I've included above. I am now proceeding to use Workspaces for each URL to obtain the chapter content. The goal is to obtain the necessary text for indexing. This information will then facilitate the creation of the index with at least 100 terms as requested. I've begun to retrieve this information.

Orchestrating Chapter Retrieval

I've extracted the chapter URLs and initiated a call to Workspaces. I'm currently retrieving the content for each chapter. To ensure a smooth process, I'm batching the calls to prevent any rate-limiting issues. This should enable me to efficiently compile the text needed for the index.

Decoding User Request

I've determined the user's need. They require two primary deliverables: first, a comprehensive list of chapter titles extracted from Google Docs, and second, a detailed index containing a minimum of one hundred key terms. The process of extracting titles seems straightforward, while curating the index will involve more nuanced analysis.

Extracting Titles and Indexing

I've successfully identified the user's need: extracting chapter titles from the provided documents and compiling a comprehensive index. I've fetched the content of 31 Google Docs, including the main document and its chapters. I've confirmed that no additional tools are needed. My plan involves two steps: first, extracting chapter titles from the document filenames, and second, meticulously processing the text to build the index with key terms and chapter locators.

Developing an Extraction Plan

I've refined my approach to tackle the user's request. I've now formulated a precise plan. Firstly, I will compile the chapter titles from the filenames of the 31 fetched documents. Secondly, and more complexly, I will meticulously analyze the content to create a comprehensive, alphabetically ordered index exceeding 100 entries. I have finalized my extraction and indexing strategy and can now commence execution.

Crafting the Extraction Strategy

My approach is well-defined. I will compile chapter titles from the filenames of the 31 fetched documents. Subsequently, I'll analyze the content meticulously to construct an alphabetically organized index exceeding 100 entries. I've finalized the extraction and indexing strategy and can now commence implementation. The user's goal of a detailed index, covering content from diverse chapters and appendices within the Agentic Design Patterns series, is now within reach. I'll focus on delivering a thorough response, going beyond a mere sample index.

Defining the Approach

I've clarified the user's need. I will extract chapter titles from the document filenames. Following that, I will carefully create an index exceeding 100 entries, arranging them

alphabetically and noting their chapter locations. I am prepared to begin the indexing and extraction process.

Glossary

Fundamental Concepts

Prompt: A prompt is the input, typically in the form of a question, instruction, or statement, that a user provides to an AI model to elicit a response. The quality and structure of the prompt heavily influence the model's output, making prompt engineering a key skill for effectively using AI.

Context Window: The context window is the maximum number of tokens an AI model can process at once, including both the input and its generated output. This fixed size is a critical limitation, as information outside the window is ignored, while larger windows enable more complex conversations and document analysis.

In-Context Learning: In-context learning is an AI's ability to learn a new task from examples provided directly in the prompt, without requiring any retraining. This powerful feature allows a single, general-purpose model to be adapted to countless specific tasks on the fly.

Zero-Shot, One-Shot, & Few-Shot Prompting: These are prompting techniques where a model is given zero, one, or a few examples of a task to guide its response. Providing more examples generally helps the model better understand the user's intent and improves its accuracy for the specific task.

Multimodality: Multimodality is an AI's ability to understand and process information across multiple data types like text, images, and audio. This allows for more versatile and human-like interactions, such as describing an image or answering a spoken question.

Grounding: Grounding is the process of connecting a model's outputs to verifiable, real-world information sources to ensure factual accuracy and reduce hallucinations. This is often achieved with techniques like RAG to make AI systems more trustworthy.

Core AI Model Architectures Transformers: The Transformer is the foundational neural network architecture for most modern LLMs. Its key innovation is the self-attention mechanism, which efficiently processes long sequences of text and captures complex relationships between words.

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN): The Recurrent Neural Network is a foundational architecture that preceded the Transformer. RNNs process information sequentially, using loops to maintain a "memory" of previous inputs, which made them suitable for tasks like text and speech processing.

Mixture of Experts (MoE): Mixture of Experts is an efficient model architecture where a "router" network dynamically selects a small subset of "expert" networks to handle any given input. This allows models to have a massive number of parameters while keeping computational costs manageable.

Diffusion Models: Diffusion models are generative models that excel at creating high-quality images. They work by adding random noise to data and then training a model to meticulously reverse the process, allowing them to generate novel data from a random starting point.

Mamba: Mamba is a recent AI architecture using a Selective State Space Model (SSM) to process sequences with high efficiency, especially for very long contexts. Its selective mechanism allows it to focus on relevant information while filtering out noise, making it a potential alternative to the Transformer.

The LLM Development Lifecycle

The development of a powerful language model follows a distinct sequence. It begins with Pre-training, where a massive base model is built by training it on a vast dataset of general internet text to learn language, reasoning, and world knowledge. Next is Fine-tuning, a specialization phase where the general model is further trained on smaller, task-specific datasets to adapt its capabilities for a particular purpose. The final stage is Alignment, where the specialized model's behavior is adjusted to ensure its outputs are helpful, harmless, and aligned with human values.

Pre-training Techniques: Pre-training is the initial phase where a model learns general knowledge from vast amounts of data. The top techniques for this involve different objectives for the model to learn from. The most common is Causal Language Modeling (CLM), where the model predicts the next word in a sentence. Another is Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where the model fills in intentionally hidden words in a text. Other important methods include Denoising Objectives, where the model learns to restore a corrupted input to its original state, Contrastive Learning, where it learns to distinguish between similar and dissimilar pieces of data, and Next Sentence Prediction

(NSP), where it determines if two sentences logically follow each other.

Fine-tuning Techniques: Fine-tuning is the process of adapting a general pre-trained model to a specific task using a smaller, specialized dataset. The most common approach is Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), where the model is trained on labeled examples of correct input-output pairs. A popular variant is Instruction Tuning, which focuses on training the model to better follow user commands. To make this process more efficient, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods are used, with top techniques including LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), which only updates a small number of parameters, and its memory-optimized version, QLoRA. Another technique,

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), enhances the model by connecting it to an external knowledge source during the fine-tuning or inference stage.

Alignment & Safety Techniques: Alignment is the process of ensuring an AI model's behavior aligns with human values and expectations, making it helpful and harmless. The most prominent technique is Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), where a "reward model" trained on human preferences guides the AI's learning process, often using an algorithm like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) for stability. Simpler alternatives have emerged, such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), which bypasses the need for a separate reward model, and Kahneman-Tversky Optimization (KTO), which simplifies data collection further. To ensure safe

deployment, Guardrails are implemented as a final safety layer to filter outputs and block harmful actions in real-time.

Enhancing AI Agent Capabilities

AI agents are systems that can perceive their environment and take autonomous actions to achieve goals. Their effectiveness is enhanced by robust reasoning frameworks.

Chain of Thought (CoT): This prompting technique encourages a model to explain its reasoning step-by-step before giving a final answer. This process of "thinking out loud" often leads to more accurate results on complex reasoning tasks.

Tree of Thoughts (ToT): Tree of Thoughts is an advanced reasoning framework where an agent explores multiple reasoning paths simultaneously, like branches on a tree. It allows the agent to self-evaluate different lines of thought and choose the most promising one to pursue, making it more effective at complex problem-solving.

ReAct (Reason and Act): ReAct is an agent framework that combines reasoning and acting in a loop. The agent first "thinks" about what to do, then takes an "action" using a tool, and uses the resulting observation to inform its next thought, making it highly effective at solving complex tasks.

Planning: This is an agent's ability to break down a high-level goal into a sequence of smaller, manageable sub-tasks. The agent then creates a plan to execute these steps in order, allowing it to handle complex, multi-step assignments.

Deep Research: Deep research refers to an agent's capability to autonomously explore a topic in-depth by iteratively searching for information, synthesizing findings, and identifying new questions. This allows the agent to build a comprehensive understanding of a subject far beyond a single search query.

Critique Model: A critique model is a specialized AI model trained to review, evaluate, and provide feedback on the output of another AI model. It acts as an automated critic, helping to identify errors, improve reasoning, and ensure the final output meets a desired quality standard.

Index of Terms

This index of terms was generated using Gemini Pro 2.5. The prompt and reasoning steps are included at the end to demonstrate the time-saving benefits and for educational purposes.

A

A/B Testing - Chapter 3: Parallelization

Action Selection - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Adaptation - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Adaptive Task Allocation - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Adaptive Tool Use & Selection - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Agent - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Agent-Computer Interfaces (ACIs) - Appendix B

Agent-Driven Economy - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Agent as a Tool - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Agent Cards - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Agent Development Kit (ADK) - Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A), Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring, Appendix C

Agent Discovery - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Agent Trajectories - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Agentic Design Patterns - Introduction

Agentic RAG - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Agentic Systems - Introduction

Al Co-scientist - Chapter 21: Exploration and DiscoveryAlignment - Glossary

AlphaEvolve - Chapter 9: Learning and AdaptationAnalogies - Appendix A

Anomaly Detection - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Anthropic's Claude 4 Series - Appendix B

Anthropic's Computer Use - Appendix B

API Interaction - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Artifacts - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Asynchronous Polling - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Audit Logs - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Automated Metrics - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE) - Appendix A

Autonomy - Introduction

A2A (Agent-to-Agent) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

B

Behavioral Constraints - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Browser Use - Appendix B

C

Callbacks - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Causal Language Modeling (CLM) - Glossary

Chain of Debates (CoD) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A

Chatbots - Chapter 8: Memory Management

ChatMessageHistory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Checkpoint and Rollback - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Chunking - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Clarity and Specificity - Appendix A

Client Agent - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Code Generation - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Code Prompting - Appendix A

CoD (Chain of Debates) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

CoT (Chain of Thought) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A

Collaboration - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent CollaborationCompliance - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Conciseness - Appendix A

Content Generation - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Context Engineering - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Context Window - Glossary

Contextual Pruning & Summarization - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Contextual Prompting - Appendix A

Contractor Model - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

ConversationBufferMemory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Conversational Agents - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 4: Reflection

Cost-Sensitive Exploration - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

CrewAl - Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 6: Planning, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns, Appendix C

Critique Agent - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Critique Model - Glossary

Customer Support - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

D

Data Extraction - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Data Labeling - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Database Integration - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

DatabaseSessionService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Debate and Consensus - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Decision Augmentation - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Decomposition - Appendix A

Deep Research - Chapter 6: Planning, Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Glossary

Delimiters - Appendix A

Denoising Objectives - Glossary

Dependencies - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Diffusion Models - GlossaryDirect Preference Optimization (DPO) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Discoverability - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)Drift Detection - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Dynamic Model Switching - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Dynamic Re-prioritization - Chapter 20: Prioritization

E

Embeddings - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Embodiment - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Energy-Efficient Deployment - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Episodic Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Error Detection - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Error Handling - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Escalation Policies - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Evaluation - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Exception Handling - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Expert Teams - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Exploration and Discovery - Chapter 21: Exploration and Discovery

External Moderation APIs - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

F

Factored Cognition - Appendix A

FastMCP - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Fault Tolerance - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Few-Shot Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Few-Shot Prompting - Appendix A

Fine-tuning - Glossary

Formalized Contract - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Function Calling - Chapter 5: Tool Use, Appendix A

G

Gemini Live - Appendix B

Gems - Appendix A

Generative Media Orchestration - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Goal Setting - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring

GoD (Graph of Debates) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Google Agent Development Kit (ADK) - Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A), Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring, Appendix C

Google Co-Scientist - Chapter 21: Exploration and Discovery

Google DeepResearch - Chapter 6: PlanningGoogle Project Mariner - Appendix B

Graceful Degradation - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery, Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Graph of Debates (GoD) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Grounding - Glossary

Guardrails - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

H

Haystack - Appendix C

Hierarchical Decomposition - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Hierarchical Structures - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

HITL (Human-in-the-Loop) - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human-on-the-loop - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

Human Oversight - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop, Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

1

In-Context Learning - Glossary

InMemoryMemoryService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

InMemorySessionService - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Input Validation/Sanitization - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Instructions Over Constraints - Appendix A

Inter-Agent Communication (A2A) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Intervention and Correction - Chapter 13: Human-in-the-Loop

IoT Device Control - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Iterative Prompting / Refinement - Appendix A

J

Jailbreaking - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

K

Kahneman-Tversky Optimization (KTO) - Glossary

Knowledge Retrieval (RAG) - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

L

LangChain - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 20: Prioritization, Appendix C

LangGraph - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Chapter 2: Routing, Chapter 3: Parallelization, Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 5: Tool Use, Chapter 8: Memory Management, Appendix C

Latency Monitoring - Chapter 19: Evaluation and MonitoringLearned Resource Allocation Policies - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Learning and Adaptation - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

LLM-as-a-Judge - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

LlamalIndex - Appendix C

LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) - Glossary

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) - Glossary

M

Mamba - Glossary

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) - Glossary

MASS (Multi-Agent System Search) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

MCP (Model Context Protocol) - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)Memory Management - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Memory-Based Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

MetaGPT - Appendix CMicrosoft AutoGen - Appendix C

Mixture of Experts (MoE) - Glossary

Model Context Protocol (MCP) - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Modularity - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety PatternsMonitoring - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring, Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

Multi-Agent Collaboration - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Multi-Agent System Search (MASS) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Multimodality - Glossary

Multimodal Prompting - Appendix A

N

Negative Examples - Appendix A

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) - Glossary

0

Observability - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

One-Shot Prompting - Appendix A

Online Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

OpenAI Deep Research API - Chapter 6: Planning

OpenEvolve - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

OpenRouter - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Output Filtering/Post-processing - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

P

PAL (Program-Aided Language Models) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Parallelization - Chapter 3: Parallelization

Parallelization & Distributed Computing Awareness - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) - Glossary

PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) - Glossary

Performance Tracking - Chapter 19: Evaluation and MonitoringPersona Pattern - Appendix A

Personalization - What makes an AI system an Agent?

Planning - Chapter 6: Planning, Glossary

Prioritization - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Principle of Least Privilege - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Proactive Resource Prediction - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Procedural Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Program-Aided Language Models (PAL) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Project Astra - Appendix B

Prompt - Glossary

Prompt Chaining - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining

Prompt Engineering - Appendix A

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Push Notifications - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Q

QLoRA - Glossary

Quality-Focused Iterative Execution - Chapter 19: Evaluation and Monitoring

R

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) - Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG), Appendix A

ReAct (Reason and Act) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques, Appendix A, Glossary

Reasoning - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Reasoning-Based Information Extraction - Chapter 10: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

Recovery - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and Recovery

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) - Glossary

Reflection - Chapter 4: Reflection

Reinforcement Learning - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) - Glossary

Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Remote Agent - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Request/Response (Polling) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Resource-Aware Optimization - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware OptimizationRetrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) - Chapter 8: Memory Management, Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG), Appendix A

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) - Glossary

RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards) - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) - Glossary

Role Prompting - Appendix ARouter Agent - Chapter 16: Resource-Aware Optimization

Routing - Chapter 2: Routing

s

Safety - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Scaling Inference Law - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Scheduling - Chapter 20: Prioritization

Self-Consistency - Appendix A

Self-Correction - Chapter 4: Reflection, Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Self-Improving Coding Agent (SICA) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

Self-Refinement - Chapter 17: Reasoning Techniques

Semantic Kernel - Appendix C

Semantic Memory - Chapter 8: Memory Management

Semantic Similarity - Chapter 14: Knowledge Retrieval (RAG)

Separation of Concerns - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Sequential Handoffs - Chapter 7: Multi-Agent Collaboration

Server-Sent Events (SSE) - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)Session - Chapter 8: Memory Management

SICA (Self-Improving Coding Agent) - Chapter 9: Learning and Adaptation

SMART Goals - Chapter 11: Goal Setting and Monitoring

State - Chapter 8: Memory Management

State Rollback - Chapter 12: Exception Handling and RecoveryStep-Back Prompting - Appendix A

Streaming Updates - Chapter 15: Inter-Agent Communication (A2A)

Structured Logging - Chapter 18: Guardrails/Safety Patterns

Structured Output - Chapter 1: Prompt Chaining, Appendix A