2.1_CPU_Configurations

2.1 CPU Configurations

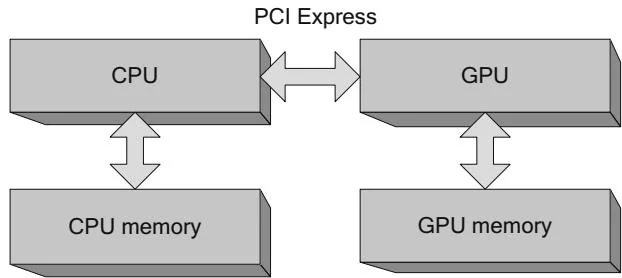

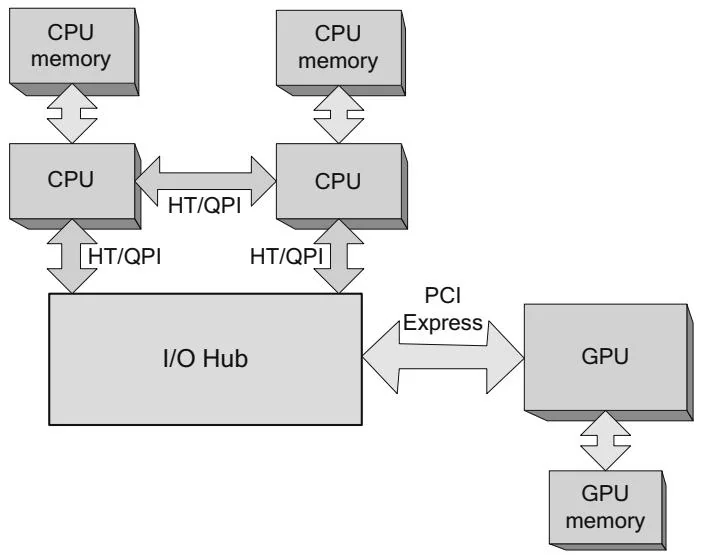

This section describes a variety of CPU/GPU architectures, with some comments on how a CUDA developer would approach programming the system differently. We examine a variety of CPU configurations, integrated GPUs, and multi-GPU configurations. We begin with Figure 2.1.

An important element that was omitted from Figure 2.1 is the "chipset" or "core logic" that connects the CPU to the outside world. Every bit of input and output of the system, including disk and network controllers, keyboards and mice, USB devices, and, yes, GPUs, goes through the chipset. Until recently, chipsets were

Figure 2.1 CPU/GPU architecture simplified.

divided into a "southbridge" that connected most peripherals to the system1 and a "northbridge" that contained the graphics bus (the Accelerated Graphics Port, until the PCI Express [PCIe] bus displaced it) and a memory controller ("front side bus") connected to the CPU memory.

Each "lane" in PCI Express 2.0 can theoretically deliver about 500MB/s of bandwidth, and the number of lanes for a given peripheral can be 1, 4, 8, or 16. GPUs require the most bandwidth of any peripheral on the platform, so they generally are designed to be plugged into 16-lane PCIe slots. With packet overhead, the 8G/s of bandwidth for such a connection delivers about 6G/s in practice.[2]

2.1.1 FRONT-SIDE BUS

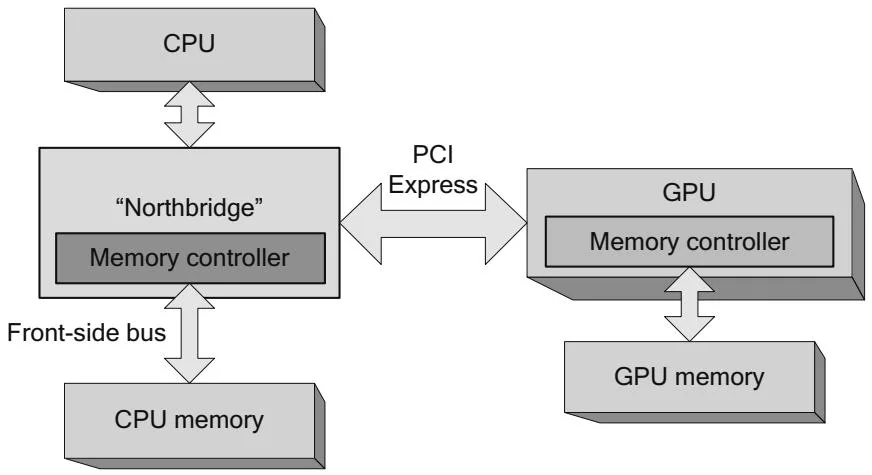

Figure 2.2 adds the northbridge and its memory controller to the original simplified diagram. For completeness, Figure 2.2 also shows the GPU's integrated memory controller, which is designed under a very different set of constraints than the CPU's memory controller. The GPU must accommodate so-called isochronous clients, such as video display(s), whose bandwidth requirements are fixed and nonnegotiable. The GPU's memory controller also is designed with the GPU's extreme latency-tolerance and vast memory bandwidth requirements in mind. As of this writing, high-end GPUs commonly deliver local GPU memory bandwidths well in excess of . GPU memory controllers are always integrated with the GPU, so they are omitted from the rest of the diagrams in this chapter.

Figure 2.2 CPU/GPU architecture—northbridge.

2.1.2 SYMMETRIC MULTIPPROCESSORS

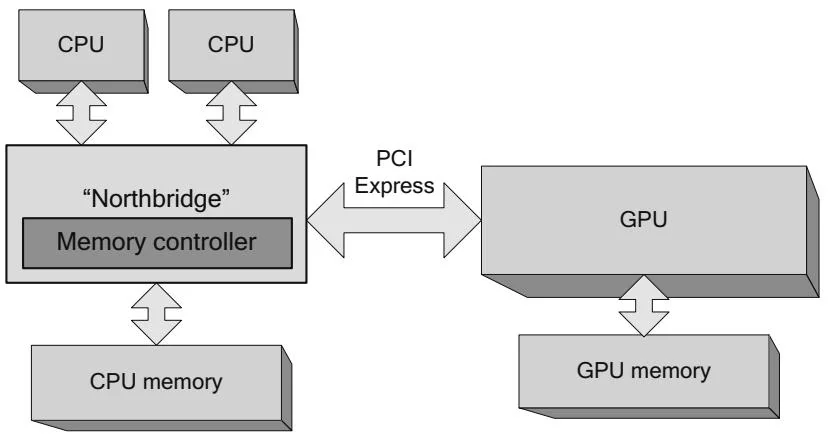

Figure 2.3 shows a system with multiple CPUs in a traditional northbridge configuration. Before multicore processors, applications had to use multiple threads to take full advantage of the additional power of multiple CPUs. The northbridge must ensure that each CPU sees the same coherent view of

Figure 2.3 Multiple CPUs (SMP configuration).

memory, even though every CPU and the northbridge itself all contain caches. Since these so-called "symmetric multiprocessor" (SMP) systems share a common path to CPU memory, memory accesses exhibit relatively uniform performance.

2.1.3 NONUNIFORM MEMORY ACCESS

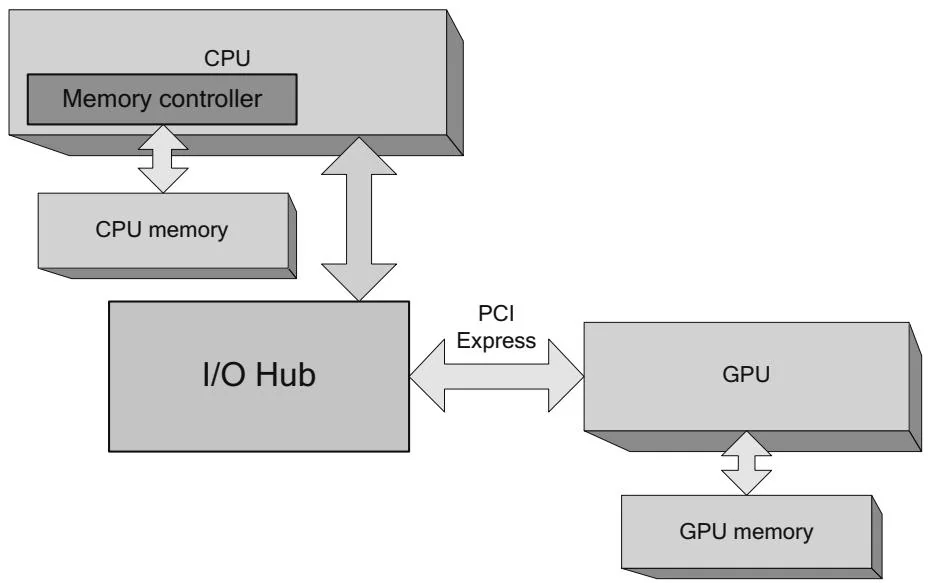

Starting with AMD's Opteron and Intel's Nehalem (i7) processors, the memory controller in the northbridge was integrated directly into the CPU, as shown in Figure 2.4. This architectural change improves CPU memory performance.

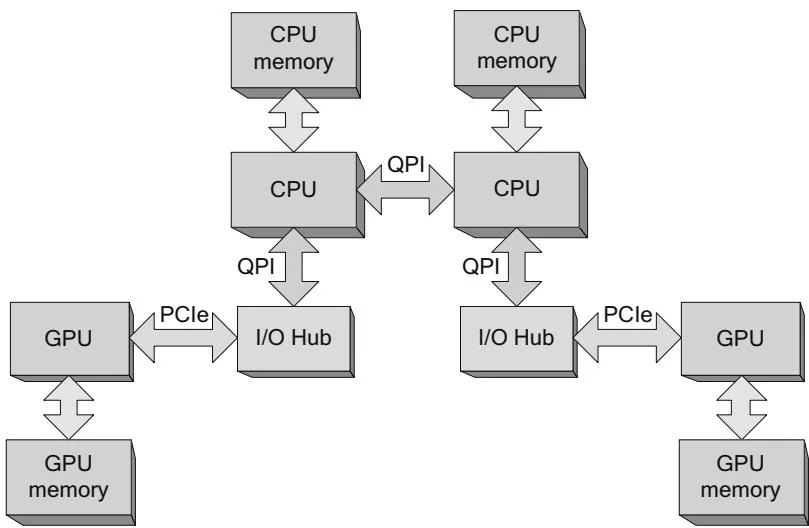

For developers, the system in Figure 2.4 is only slightly different from the ones we've already discussed. For systems that contain multiple CPUs, as shown in Figure 2.5, things get more interesting.

For machine configurations with multiple CPUs, this architecture implies that each CPU gets its own pool of memory bandwidth. At the same time, because multithreaded operating systems and applications rely on the cache coherency enforced by previous CPUs and northbridge configurations, the Opteron and

Figure 2.4 CPU with integrated memory controller.

Figure 2.5 Multiple CPUs (NUMA).

Nehalem architectures also introduced HyperTransport (HT) and QuickPath Interconnect (QPI), respectively.

HT and QPI are point-to-point interconnects that connect CPUs to other CPUs, or CPUs to I/O hubs. On systems that incorporate HT/QPI, any CPU can access any memory location, but accesses are much faster to "local" memory locations whose physical address is in the memory directly attached to the CPU. Nonlocal accesses are resolved by using HT/QPI to snoop the caches of other CPUs, evict any cached copies of the requested data, and deliver the data to the CPU that performed the memory request. In general, the enormous on-chip caches on these CPUs mitigate the cost of these nonlocal memory accesses; the requesting CPU can keep the data in its own cache hierarchy until the memory is requested by another CPU.

To help developers work around these performance pitfalls, Windows and Linux have introduced APIs to enable applications to steer their allocations toward specific CPUs and to set CPU "thread affinities" so the operating system schedules threads onto CPUs so most or all of their memory accesses will be local.

A determined programmer can use these APIs to write contrived code that exposes the performance vulnerabilities of NUMA, but the more common (and insidious!) symptom is a slowdown due to "false sharing" where two threads running on different CPUs cause a plethora of HT/QPI transactions by accessing

memory locations that are in the same cache line. So NUMA APIs must be used with caution: Although they give programmers the tools to improve performance, they also can make it easy for developers to inflict performance problems on themselves.

One approach to mitigating the performance impact of nonlocal memory accesses is to enable memory interleaving, in which physical memory is evenly split between all CPUs on cache line boundaries. For CUDA, this approach works well on systems that are designed exactly as shown in Figure 2.5, with multiple CPUs in a NUMA configuration connected by a shared I/O hub to the GPU(s). Since PCI Express bandwidth is often a bottleneck to overall application performance, however, many systems have separate I/O hubs to service more than one PCI Express bus, as shown in Figure 2.6.

In order to run well on such "affinitized" systems, CUDA applications must take care to use NUMA APIs to match memory allocations and thread affinities to the PCI Express bus attached to a given GPU. Otherwise, memory copies initiated by the GPU(s) are nonlocal, and the memory transactions take an extra "hop" over the HT/QPI interconnect. Since GPUs demand a huge amount of bandwidth, these DMA operations reduce the ability of HT/QPI to serve its primary purpose. Compared to false sharing, the performance impact of nonlocal GPU memory copies is a much more plausible performance risk for CUDA applications.

Figure 2.6 Multi-CPU (NUMA configuration), multiple buses.

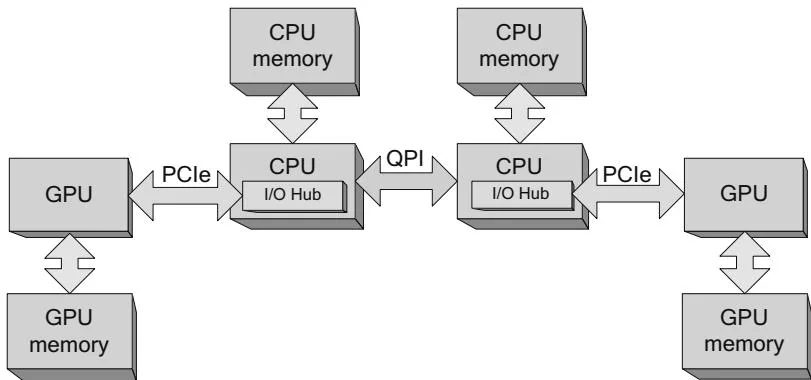

Figure 2.7 Multi-CPU with integrated PCI Express.

2.1.4 PCI EXPRESS INTEGRATION

Intel's Sandy Bridge class processors take another step toward full system integration by integrating the I/O hub into the CPU, as shown in Figure 2.7. A single Sandy Bridge CPU has up to 40 lanes of PCI Express bandwidth (remember that one GPU can use up to 16 lanes, so 40 are enough for more than two full-size GPUs).

For CUDA developers, PCI Express integration brings bad news and good news. The bad news is that PCI Express traffic is always affinitized. Designers cannot build systems like the system in Figure 2.5, where a single I/O hub serves multiple CPUs; all multi-CPU systems resemble Figure 2.6. As a result, GPUs associated with different CPUs cannot perform peer-to-peer operations. The good news is that the CPU cache can participate in PCI Express bus traffic: The CPU can service DMA read requests out of cache, and writes by the GPU are posted to the CPU cache.