2.5_CPU_GPU_Interactions

2.5 CPU/GPU Interactions

This section describes key elements of CPU-GPU interactions.

Pinned host memory: CPU memory that the GPU can directly access

Command buffers: the buffers written by the CUDA driver and read by the GPU to control its executionCPU/GPU synchronization: how the GPU's progress is tracked by the CPU

This section describes these facilities at the hardware level, citing APIs only as necessary to help the reader understand how they pertain to CUDA development. For simplicity, this section uses the CPU/GPU model in Figure 2.1, setting aside the complexities of multi-CPU or multi-GPU programming.

2.5.1 PINNED HOST MEMORY AND COMMAND BUFFERS

For obvious reasons, the CPU and GPU are each best at accessing its own memory, but the GPU can directly access page-locked CPU memory via direct memory

access (DMA). Page-locking is a facility used by operating systems to enable hardware peripherals to directly access CPU memory, avoiding extraneous copies. The "locked" pages have been marked as ineligible for eviction by the operating system, so device drivers can program these peripherals to use the pages' physical addresses to access the memory directly. The CPU still can access the memory in question, but the memory cannot be moved or paged out to disk.

Since the GPU is a distinct device from the CPU, direct memory access also enables the GPU to read and write CPU memory independently of, and in parallel with, the CPU's execution. Care must be taken to synchronize between the CPU and GPU to avoid race conditions, but for applications that can make productive use of CPU clock cycles while the GPU is processing, the performance benefits of concurrent execution can be significant.

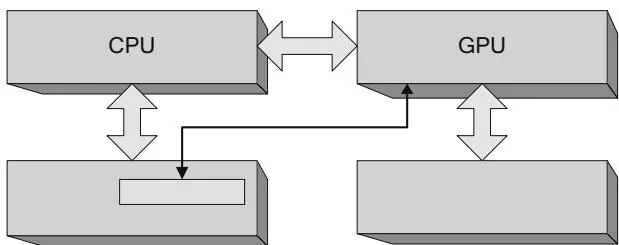

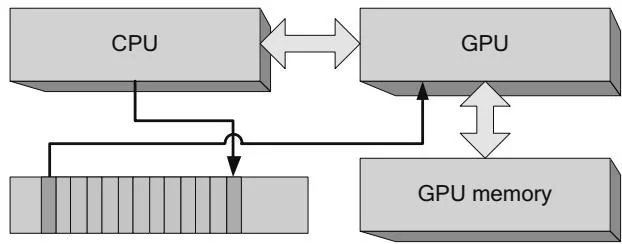

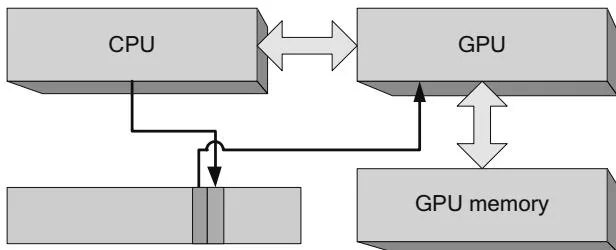

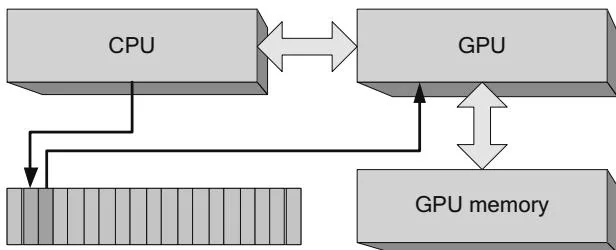

Figure 2.21 depicts a "pinned" buffer that has been mapped by the for direct access. CUDA programmers are familiar with pinned buffers because CUDA has always given them the ability to allocate pinned memory via APIs such as CUDAMallocHost(). But under the hood, one of the main applications for such buffers is to submit commands to the GPU. The CPU writes commands into a "command buffer" that the GPU can consume, and the GPU simultaneously reads and executes previously written commands. Figure 2.22 shows how the CPU and GPU share this buffer. This diagram is simplified because the commands may be hundreds of bytes long, and the buffer is big enough to hold several thousand such commands. The "leading edge" of the buffer is under construction by the CPU and not yet ready to be read by the GPU. The "trailing edge" of the buffer is being read by the GPU. The commands in between are ready for the GPU to process when it is ready.

Figure 2.21 Pinned buffer.

Figure 2.22 CPU/GPU command buffer.

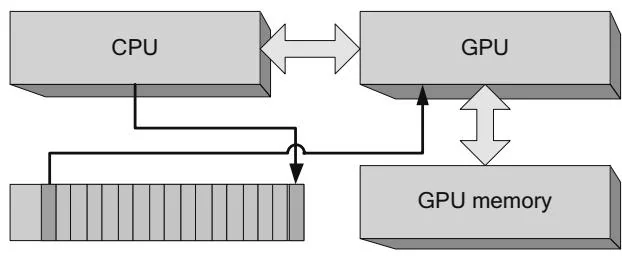

Typically, the CUDA driver will reuse command buffer memory because once the GPU has finished processing a command, the memory becomes eligible to be written again by the CPU. Figure 2.23 shows how the CPU can "wrap around" the command buffer.

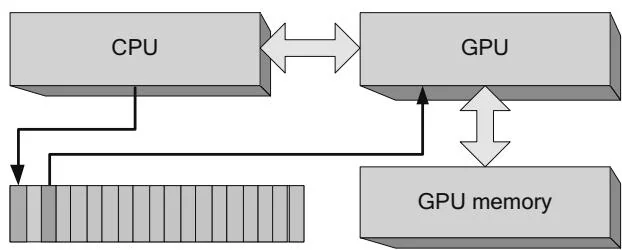

Since it takes several thousand CPU clock cycles to launch a CUDA kernel, a key use case for CPU/GPU concurrency is simply to prepare more GPU commands while the GPU is processing. Applications that are not balanced to keep both the CPU and GPU busy may become "CPU bound" or "GPU bound," as shown in Figures 2.24 and 2.25, respectively. In a CPU-bound application, the GPU is poised and ready to process the next command as soon as it becomes available; in a GPU-bound application, the CPU has completely filled the command buffer and

Figure 2.23 Command buffer wrap-around.

Figure 2.24 GPU-bound application.

Figure 2.25 CPU-bound application.

must wait for the GPU before writing the next GPU command. Some applications are intrinsically CPU-bound or GPU-bound, so CPU- and GPU-boundedness does not necessarily indicate a fundamental problem with an application's structure. Nevertheless, knowing whether an application is CPU-bound or GPU-bound can help highlight performance opportunities.

2.5.2 CPU/GPU CONCURRENCY

The previous section introduced the coarsest-grained parallelism available in CUDA systems: CPU/GPU concurrency. All launches of CUDA kernels are asynchronous: the CPU requests the launch by writing commands into the command buffer, then returns without checking the GPU's progress. Memory copies optionally also may be asynchronous, enabling CPU/GPU concurrency and possibly enabling memory copies to be done concurrently with kernel processing.

Amdahl's Law

When CUDA programs are written correctly, the CPU and GPU can fully operate in parallel, potentially doubling performance. CPU- or GPU-bound programs do not benefit much from CPU/GPU concurrency because the CPU or GPU will limit

performance even if the other device is operating in parallel. This vague observation can be concretely characterized using Amdahl's Law, first articulated in a paper by Gene Amdahl in 1967. Amdahl's Law is often summarized as follows.

where and represents the ratio of the sequential portion. This formulation seems awkward when examining small-scale performance opportunities such as CPU/GPU concurrency. Rearranging the equation as follows

clearly shows that the speedup is . If there is one CPU and one GPU ( ), the maximum speedup from full concurrency is ; this is almost achievable for balanced workloads such as video transcoding, where the CPU can perform serial operations (such as variable-length decoding) in parallel with the GPU's performing parallel operations (such as pixel processing). But for more CPU- or GPU-bound applications, this type of concurrency offers limited benefits.

Amdahl's paper was intended as a cautionary tale for those who believed that parallelism would be a panacea for performance problems, and we use it elsewhere in this book when discussing intra-GPU concurrency, multi-GPU concurrency, and the speedups achievable from porting to CUDA kernels. It can be empowering, though, to know which forms of concurrency will not confer any benefit to a given application, so developers can spend their time exploring other avenues for increased performance.

Error Handling

CPU/GPU concurrency also has implications for error handling. If the CPU launches a dozen kernels and one of them causes a memory fault, the CPU cannot discover the fault until it has performed CPU/GPU synchronization (described in the next section). Developers can manually perform CPU/GPU synchronization by calling CUDAThreadSynchronize() or cuCtxSynchronize(), and other functions such as cuadaFree() or cuMemFree() may cause CPU/GPU synchronization to occur as a side effect. The CUDA C Programming Guide references this behavior by calling out functions that may cause CPU/GPU synchronization:

"Note that this function may also return error codes from previous, asynchronous launches."

As CUDA is currently implemented, if a fault does occur, there is no way to know which kernel caused the fault. For debug code, if it's difficult to isolate faults with synchronization, developers can set the CUDA-LaUNCH_BLOCKING environment variable to force all launches to be synchronous.

CPU/GPU Synchronization

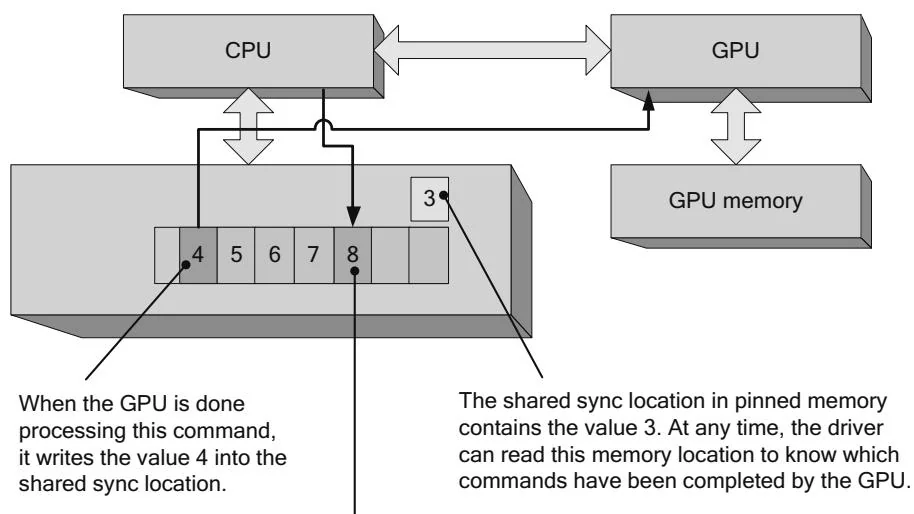

Although most GPU commands used by CUDA involve performing memory copies or kernel launches, an important subclass of commands helps the CUDA driver track the GPU's progress in processing the command buffer. Because the application cannot know how long a given CUDA kernel may run, the GPU itself must report progress to the CPU. Figure 2.26 shows both the command buffer and the "sync location" (which also resides in pinned host memory) used by the driver and GPU to track progress. A monotonically increasing integer value (the "progress value") is maintained by the driver, and every major GPU operation is followed by a command to write the new progress value to the shared sync location. In the case of Figure 2.26, the progress value is 3 until the GPU finishes executing the command and writes the value 4 to the sync location.

Figure 2.26 Shared sync value-before.

The driver keeps track of a monotonically increasing value to track the GPU's progress. Every major operation, such as a memcpy or kernel launch, is followed by a command to the GPU to write this new value to the shared sync location.

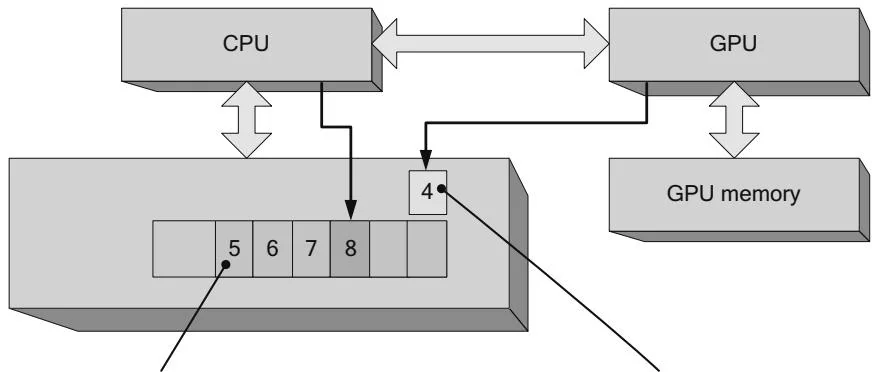

Figure 2.27 Shared sync value—after.

When the GPU is done processing this command, it will write the value 5 into the shared sync location.

The GPU has written the value 4 into the shared sync location, so the driver can see that the previous command has been executed.

CUDA exposes these hardware capabilities both implicitly and explicitly. Context-wide synchronization calls such as cuCtxSynchronize() or CUDAThreadSynchronize() simply examine the last sync value requested of the GPU and wait until the sync location attains that value. For example, if the command 8 being written by the CPU in Figure 2.27 were followed by cuCtxSynchronize() or cuadaThreadSynchronize(), the driver would wait until the shared sync value became greater than or equal to 8.

CUDA events expose these hardware capabilities more explicitly. cuEvent-Record() enforces a command to write a new sync value to a shared sync location, and cuEventQuery() and cuEventSynchronize() examine and wait on the event's sync value, respectively.

Early versions of CUDA simply polled shared sync locations, repeatedly reading the memory until the wait criterion had been achieved, but this approach is expensive and only works well when the application doesn't have to wait long (i.e., the sync location doesn't have to be read many times before exiting because the wait criterion has been satisfied). For most applications, interrupt-based schemes (exposed by CUDA as "blocking syncs") are better because they enable the CPU to suspend the waiting thread until the GPU signals an interrupt. The driver maps the GPU interrupt to a platform-specific thread synchronization primitive, such as Win32 events or Linux signals, that can be used to suspend the CPU thread if the wait condition is not true when the application starts to wait.

Applications can force the context-wide synchronization to be blocking by specifying CUCTX_BLOCKING_SYNC to cuCtxCreate() or CUDADeviceBlockingSync to CUDASetDeviceFlags(). It is preferable, however, to use blocking CUDA events (specify CU_EVENT_BLOCKING_SYNC to cuEventCreate() or CUDAEvent-BlockingSync to CUDAEventCreate(), since they are more fine-grained and interoperate seamlessly with any type of CUDA context.

Astute readers may be concerned that the CPU and GPU read and write this shared memory location without using atomic operations or other synchronization primitives. But since the CPU only reads the shared location, race conditions are not a concern. The worst that can happen is the CPU reads a "stale" value that causes it to wait a little longer than it would otherwise.

Events and Timestamps

The host interface has an onboard high-resolution timer, and it can write a timestamp at the same time it writes a 32-bit sync value. CUDA uses this hardware facility to implement the asynchronous timing features in CUDA events.

2.5.3 THE HOST INTERFACE AND INTRA-GPU SYNCHRONIZATION

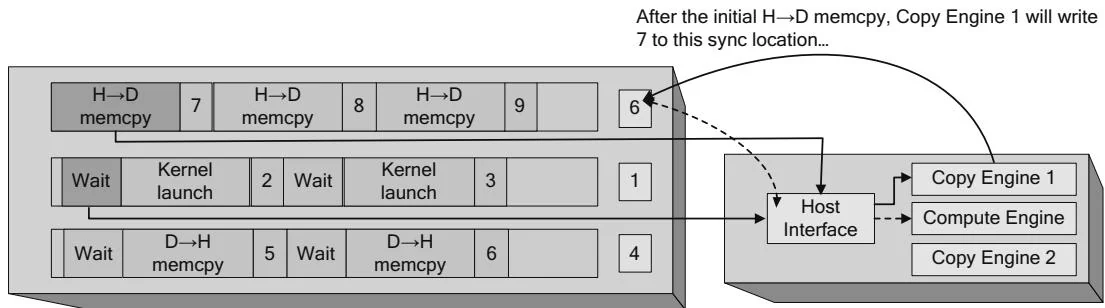

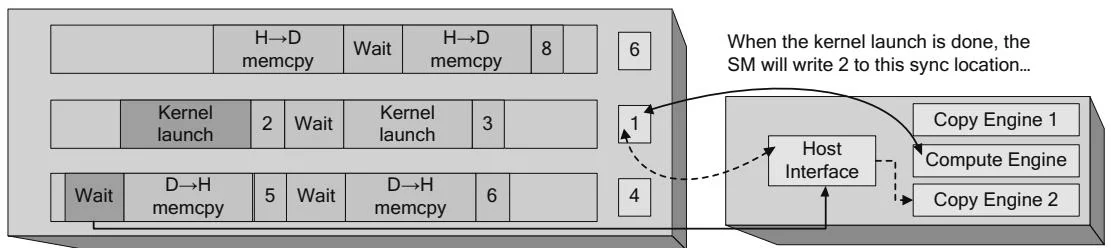

The GPU may contain multiple engines to enable concurrent kernel processing and memory copying. In this case, the driver will write commands that are dispatched to different engines that run concurrently. Each engine has its own command buffer and shared sync value, and the engine's progress is tracked as described in Figures 2.26 and 2.27. Figure 2.28 shows this situation, with two copy engines and a compute engine operating in parallel. The host interface is responsible for reading the commands and dispatching them to the appropriate engine. In Figure 2.28, a host device memcpy and two dependent operations—a kernel launch and a device host memcpy—have been submitted to the hardware. In terms of CUDA programming abstractions, these operations are within the same stream. The stream is like a CPU thread, and the kernel launch was submitted to the stream after the memcpy, so the CUDA driver must insert GPU commands for intra-GPU synchronization into the command streams for the host interface.

As Figure 2.28 shows, the host interface plays a central role in coordinating the needed synchronization for streams. When, for example, a kernel must not be launched until a needed memcpy is completed, the DMA unit can stop giving commands to a given engine until a shared sync location attains a certain value.

...and before dispatching the dependent kernel launch, Host must wait until Copy Engine 1's sync value

Figure 2.28 Intra-GPU synchronization.

...while Host Interface waits for the sync value to equal 2 before dispatching this memcpy.

This operation is similar to CPU/GPU synchronization, but the GPU is synchronizing different engines within itself.

The software abstraction layered on this hardware mechanism is a CUDA stream. CUDA streams are like CPU threads in that operations within a stream are sequential and multiple streams are needed for concurrency. Because the command buffer is shared between engines, applications must "software-pipeline" their requests in different streams. So instead of

foreach stream

Memcpy device←host

Launch kernel

Memcpy host←devicethey must implement

foreach stream

Memcpy device←host

foreach stream

Launch kernel

foreach stream

Memcpy host←deviceWithout the software pipelining, the DMA engine will "break concurrency" by synchronizing the engines to preserve each stream's model of sequential execution.

Multiple DMA Engines on Kepler

The latest Kepler-class hardware from NVIDIA implements a DMA unit per engine, obviating the need for applications to software-pipeline their streamed operations.

2.5.4 INTER-GPU SYNCHRONIZATION

Since the sync location in Figures 2.26 through 2.28 is in host memory, it can be accessed by any of the GPUs in the system. As a result, in CUDA 4.0, NVIDIA was able to add inter-GPU synchronization in the form of cuaStreamWaitEvent(). These API calls cause the driver to insert wait commands for the host interface into the current GPU's command buffer, causing the GPU to wait until the given event's sync value has been written. Starting with CUDA 4.0, the event may or may not be signaled by the same GPU that is doing the wait. Streams have been promoted from being able to synchronize execution between hardware units on a single GPU to being able to synchronize execution between GPUs.